Learn the different hiking trail types and anatomy you may see on your next adventure.

You love to hike, but do you know the names of different trail formats and the common components you’ll encounter on an outing? The following is excerpted and adapted from the newly updated AMC’s Complete Guide to Trail Building and Maintenance, 5th ed.

The general trail format will most likely be determined by the initial scope of the proposed project and therefore its use. Three major formats can be combined to compose a trail system.

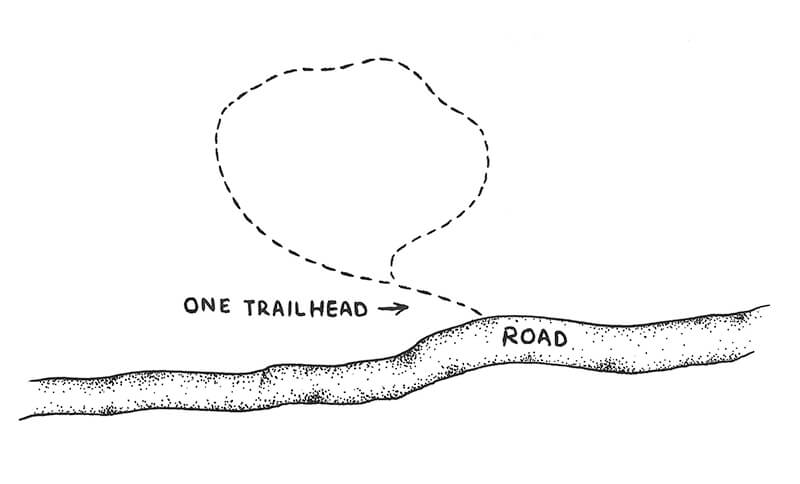

The loop.

The Loop

The loop is popular for day-use trails because it enables easy access and parking. Hikers do not have to return on the same trail, thus maximizing interest and satisfaction.

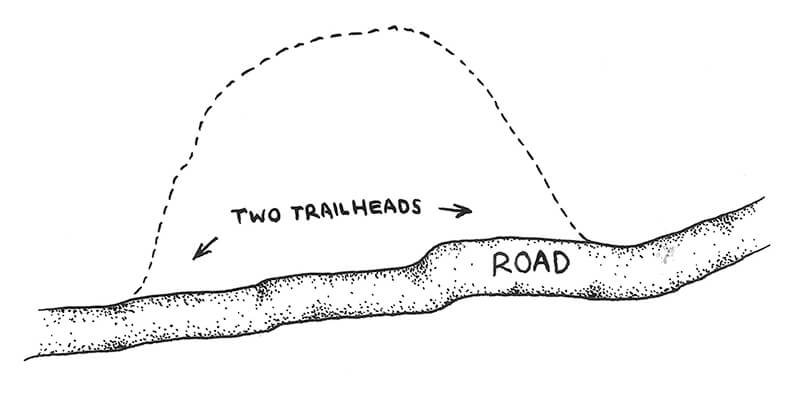

The horseshoe.

The Horseshoe

The horseshoe, which sports two separate trailheads, can be especially valuable in areas where public transportation is available. It can also be used as an alternative to auto travel on roads where distances between terminuses are not too great. Ski touring trail development in the Mount Washington Valley of New Hampshire has trailheads at inns and restaurants in the valley that are connected by trails in the horseshoe format.

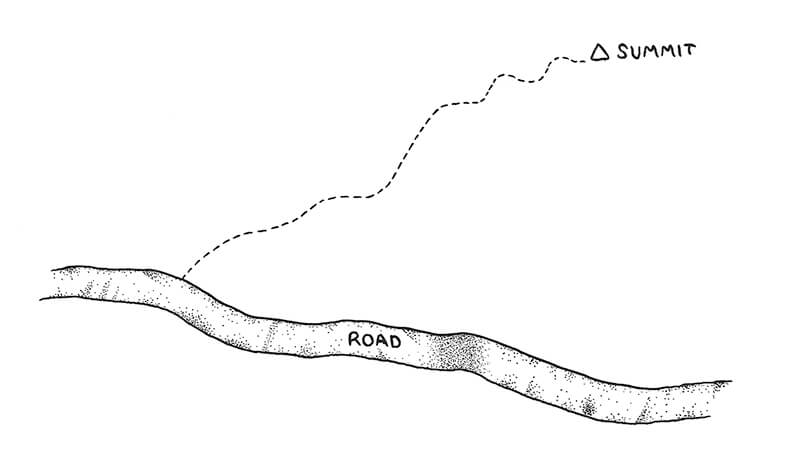

The line format, or out and back.

The Line Format (Out and Back)

The line format, also known as “out and back,” is the simplest and most common format for trails. It connects two points—the roadside trailhead and the destination. Good examples are fire wardens’ trails to lookout towers on mountain summits. Long-distance trails, such as the Appalachian Trail and Pacific Crest Trail, are prime examples of trails in the line format. Line-style trails with high scenic value are augmented with side paths, alternate routes, and connectors to form trail systems.

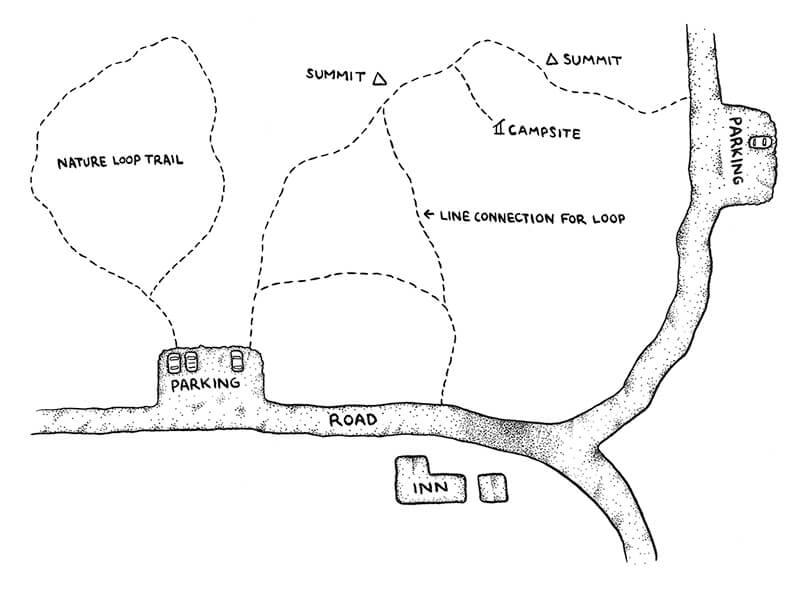

A trail system.

A Trail System

A trail system combines formats to satisfy diverse recreation needs. Careful design will provide trails for various users with different expectations. Multi-day backpackers, day hikers, and others all can be served by a well-designed system.

The treadway, or footpath, is an important piece of trail anatomy.

Understanding Trail Anatomy

All trails have termini: the trailhead, or start of the trail (usually at roadside), and the destination, which could be a mountain summit, waterfall, historic site, or other notable feature. Destinations along any single trail in a system can also include other paths and possible campsites or overnight facilities.

The trail treadway, or trail tread, is the surface upon which the hiker makes direct contact with the ground (see figure 1.5). The treadway is the most important com-ponent of any foot trail. All improvements to a natural surface treadway are made to conserve soil resources while protecting surrounding vegetation and bodies of water. These improvements (which often also make hiking easier) usually involve tread hardening and soil stabilization to prevent the trail from shifting, eroding, or becoming muddy. Popular routes in sensitive areas, such as slopes and wet terrain, will inevitably be damaged; therefore, effective maintenance of the treadway may require reconstruction and rehabilitation of the original soil profile.

The trail clearing limit is the area around the treadway that is cleared for passage of hikers (see figure 1.6). The trail clearing width is usually 4 to 6 feet wide, and the trail clearing height is usually 8 to 12 feet, depending on intended use and landowner/agency management directives. If a trail has other uses besides hiking, such as cross-country skiing or mountain biking, the corridor will be wider.

Within the trail clearing limit, the treadway is the traveled path, and the adjacent area on the slope comprises the backslope and downslope. The backslope is above the treadway and the downslope is below. Both features are important to consider when dealing with clearing limits for the trail and tread stability.

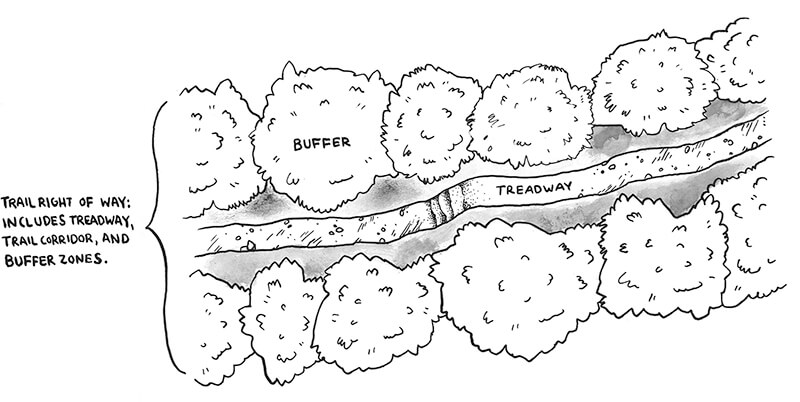

A buffer zone clearly establishes the trail corridor.

The buffer zone, or protective zone, is the space on each side of the trail clearing (see figure 1.7). Buffer zones diminish the impact of activities detrimental to the hiking experience, such as residential development, mining, or logging. While hikers may still hear, see, or even smell such activities, the buffer does provide some degree of mitigation. Buffers are also used to protect particularly fragile areas from hikers. Trail layout around sensitive plant communities, riparian areas, and exemplary ecological communities should include buffers to protect these sites from becoming disturbed by trail traffic (see figure 1.8).

The trail corridor includes the treadway, clearing limit, buffer zones, and all the lands that make up the environment surrounding the trail (see figure 1.7). The U.S. Forest Service has called it the “zone of travel influence.” This area is the most likely to be affected by trail traffic and to have an impact on the hiker’s experience.

In particularly important trail systems, such as the Appalachian Trail and other routes governed by legislative authority within the National Trails System, the trail corridor takes on added importance. Legislation passed by the United States Congress requires that the corridor of the Appalachian Trail be protected from developments that would be detrimental to its natural quality. Virtually the entire Appalachian Trail and its zone of influence are protected by a corridor averaging 1,000 feet. However, in open forests, on lakeshores, and above treeline the delineated corridor does not adequately include all the zone of influence as the landscape seen by the hiker includes the trail’s “view shed.”