This article was originally published in the Winter/Spring 2022 issue of Appalachia.

Note: Please keep in mind that hikers should never rely on apps as their main form of navigation—bringing a paper map and compass is ideal.

In her 2019 Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World (St. Martin’s Press), M. R. O’Connor tracks the growth of the GPS market, from 500 million in 2010, to 1.1 billion in 2014, to an estimated 7 billion in 2022. “What happens,” she asks, “when we outsource navigation to a gadget?”

Although professional and more seasoned backcountry travelers are likely using the apps and hybrid approaches described by Scott Berkley in this issue, apps such as FatMap (free for limited access; $29.99/year for upgrade), OnX Backcountry (free trial, then $29.99/year to start, increasing to $39.99), and AllTrails have sprung up for those more inclined towards, in O’Connor’s words, the “relentless goal of greater efficiency and convenience.”

AllTrails dominates the recreational market, and, to be clear, it is a market. In January 2021, AllTrails announced that it had reached 25 million registered users, including one million Pro upgrade subscribers ($29.99/year or $59.99/three years). AllTrails covers 190 countries on the seven continents and has published some 200,000 trail guides.

Calling AllTrails’ products “published trail guides” is worthy of exploration. As Appalachia readers surely know, trail guides such as the Appalachian Mountain Club’s White Mountain Guide are built from arduous, time-tested, and costly investments involving expert field scouting, paid authors, editors, and fact-checkers. Many guides, including AMC’s, also are published in a not-for-profit context. Apps like AllTrails, by contrast, are profit-driven, designed to commodify both use and user.

In addition to collecting data from government agencies and private companies, AllTrails open sources and crowdsources its data. This means that locations and names, elevations, contour lines, slope shading, and other information can be incorrect or outdated. (An AllTrails spokesperson could not provide timely comment, saying the company was “heads-down” and planning.)

In a June 2021 critique for SectionHiker.com, “Why Do GPS Navigation Apps Lie?,” Philip Werner discusses this and other gaps. AllTrails relies on what he calls recreational-level GPS functions, rather than more accurate GPS receivers used by mapmakers, which cost more money. This means that distance calculations also can sometimes be incorrect.

Meanwhile, across apps and devices generally, the zoom function obfuscates critical surrounding detail, placing hikers at the center of a decontextualized universe. Each hiker’s blue dot stands as, in the words of Underland author and naturalist Robert MacFarlane, “cartographically speaking . . . a perfect example of solipsism.”* And solipsism, any seasoned trip leader will tell you, is a risky proposition when it comes to decision-making in the backcountry. (And, some scientists say, a risky proposition everywhere else, too. The neuroscientist Veronique Bohbot has opted out of satellite navigation devices altogether, for instance, because research suggests that reliance on GPS increases the risk of neurodegenerative disease.)

Finally, coverage is sketchy in many places, including the Whites, and, as Parker Peltzer, visitor services supervisor at AMC’s Pinkham Notch Visitor Center, said when we talked, “Cell phone batteries go fast when there’s limited service.”

The landscape is ever changing and maturing, however, and improvements in all these areas are sure to come. For now, as technologies and our relationships to them evolve, AllTrails—and any app, however sophisticated—is still most safely and responsibly used in tandem with waterproof maps, a magnetic compass, an extra battery pack, and an additional source of illumination.

“It’s great to know where you are and how far you have to go,” AMC’s Peltzer said. “But I have seen apps recommend campsites that are not legal, challenging hikes for beginners when there are more appropriate trails in the same vicinity, and doing trails going downhill that really should be done uphill.”

Although the future of how humans will make their way through the wilderness in the digital age is uncharted and unfolding, the present appears clear: What happens when we outsource navigation to a gadget is that more people get out and get lost, meaning the people whose job it is to find us are increasingly taxed.

Says Col. Kevin Jordan of New Hampshire Fish and Game, the agency responsible for rescues in the Whites, says, “Trail apps are responsible for getting people into trouble with wrong information. We need to be telling people publicly. If it were one or two people, it could be user error, but it’s lots of people, so we want to get word out. I’m not telling people not to use it, but you can’t beat a paper map.” Until apps improve, Col. Jordan still recommends using AMC’s White Mountain Guide when in the Whites. “It’s very accurate.” [Editor’s note: The guide’s publisher also publishes this journal.]

In MacFarlane’s words, “We might best imagine wayfinding not as a skill or art but as an ethic.” Popular apps such as AllTrails are efficient, fun, convenient, and profitable, but they only work as well, and as responsibly, as their human companions.

—Catherine Buni

* Robert MacFarlane, “The Landscapes Inside Us,” New York Review of Books, July 1, 2021.

Other Trail Apps

Cal Topo

Caltopo.com

Free for basic maps, $20/year for offline mobile version, $50/year for pro version, $100/year for desktop version that includes GIS.

Avenza

Avenzamaps.com

Individual maps available from many mapmakers ranging from no cost to $5 or more; pro subscription, $129/year.

Gaia GPS

gaiagps.com

Free to view maps with cell reception, $39.99/year for premium to download maps.

Apps for Trail Adventure Planning

FatMap (free, with monthly subscriptions for more features through app stores).

AllTrails (free for basic version, $29.99/year for pro version).

OnX Backcountry (free for basic maps and weather, starting at $29.99/year, then $39.99/year for a premium subscription).

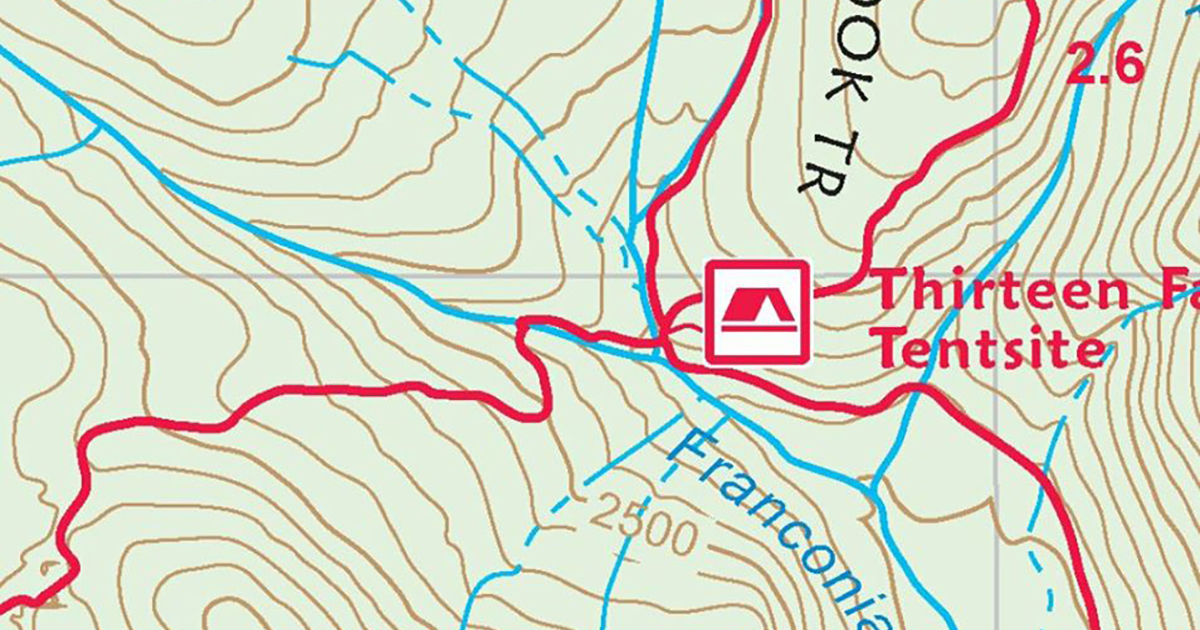

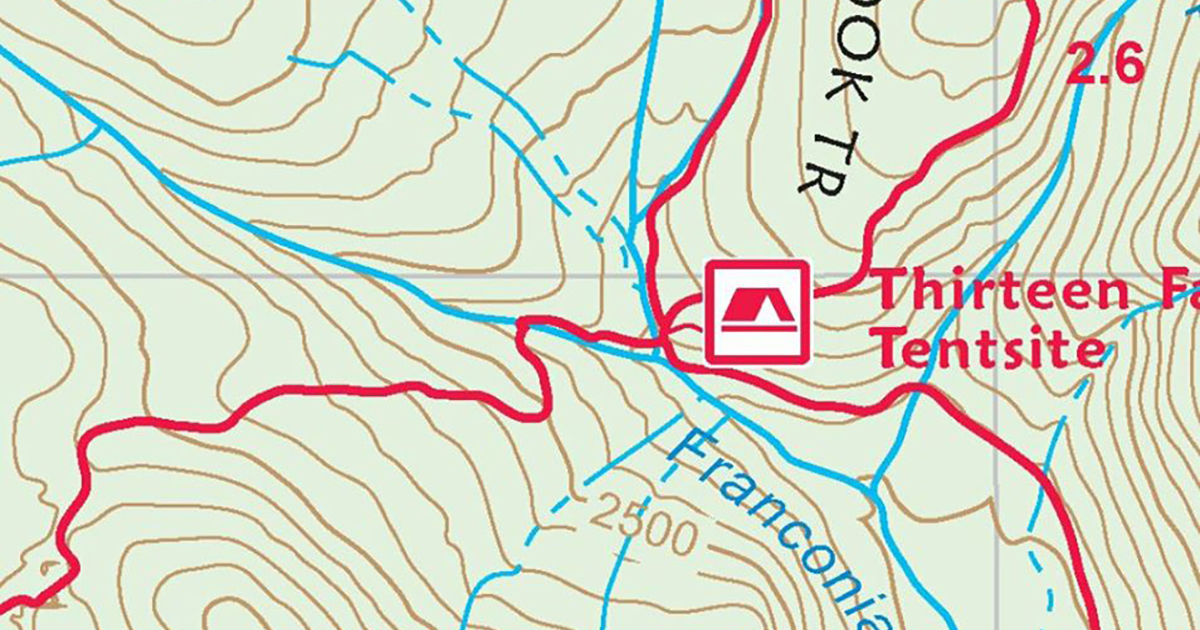

Maps as we know them are square, and their squareness is a large part of their utility. They can be folded into neat rectangles and stuffed into accessible pockets for a hike or a ski tour, unfolded and spread out to contemplate a wider trajectory, or compacted to view an area in tighter detail. Once home, the same map can spread out on a wall or tabledecoratively as it waits for the next trip. Their squareness, however, is also their undoing: if you are to select, say, the Franconia–Pemigewasset map from among an AMC White Mountain Guide map set—as many readers of this journalsurely have at one point or another—you run the risk of wandering, quite literally, off the map, into the next territory not covered by your chosen rectangle. You descend north on the Kedron Flume Trail into Crawford Notch and suddenly,whether you knew it or not, your itinerary is unmapped.

For most of its career, digital mapping for backcountry adventurers has aimed to bring the physical forms of all those square maps we know and love together at last, making for a kind of total cartography accessible from any smartphone—provided you have cell service, at least. This was the premise of CalTopo, the first digital mapping software I encountered, in my not-so-tech-savvy way, in the early 2010s. CalTopo, with its premise of superimposing Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) grids onto digital scans of existing U.S. Geological Survey quadrants, now seems rather quaint, but back then, it was a revelation to outdoors people: Here was a way to plan routes from any internet-equipped computer, no print map-set required.

It wasn’t long before CalTopo’s functions were making their way onto smaller screens by way of a mobile application called Avenza, which allowed the user to pre-plot routes on a computer using CalTopo’s mapping feature, then download their route as a geospatial PDF to Avenza for use in concert with a GPS in the field. Much in the way of Google Maps for driving, smartphone-equipped hikers or skiers could locate themselves on Avenza, which would combine theirphone’s GPS accuracy with the map plot sourced from CalTopo.

Pulling geospatial PDFs from CalTopo to reference in the field with Avenza is, in effect, just an updating of the “create a map online, print it for reference” system that still survives, especially among those of a certain generation who aren’t averse to using their desktops for research and would rather not pull their phones out for navigational purposes onceon the trails. Even the millennial or generation Xer who doesn’t mind opening Avenza during, say, a ski tour that requires a tricky cliff pass to exit a summit snowfield has done the heavy lifting at home while making a trail plan with CalTopo on the computer. At home, that skier probably also consulted some combination of print guidebooks, the internet, a localavalanche forecast, and several buddies on a group text about the next day’s plan. This heavy emphasis on preplanning thatthe CalTopo–Avenza combination entails is precisely why it is so often used in outdoor learning environments such as avalanche courses. As much as Avenza helps the skier stay found once in the field, doing research to put together a tour plan on CalTopo puts them in the mindset, once out there, of avoiding terrain traps, staying out from under avalanche paths, and making go/no-go decisions at critical moments.

The skier, hiker, climber, or runner undertakes, in sitting at the computer, what gear reviewer Tam McTavish called“the ritual of plotting and planning a route.”* But what we, as outdoors people but also as phone users, seem to want more and more is not ritualized advanced planning, but on-the-spot decision-making with curated information at our fingertips.

Apps such as FatMap, AllTrails, and OnX Backcountry have sprung up to fill that space, offering not just a digital canvason which to trace a route, but a fully realized platform to decide on a hike or ski tour at a moment’s notice. The sheer volume of data and content involved in these apps, some crowdsourced and some professionally curated, astounds: Equipped with the FatMap app, hikers can enter the woods and, cell phone service permitting, decide their route mid-hike based on a three-dimensional visualization of the terrain ahead, real-time weather data, and even by seeing which friends of theirs have done the route recently. In the AllTrails app, which has achieved an unusual ubiquity among new hikers during the backcountry influx of the past two years, the focus swings from 3D visuals to user-generated content, allowing users to make decisions based on route popularity, average time of completion, and a Yelp-esque star-rating system. Using either app, one feels less dependent on an ability to make route selections or conditions assessments germane to the terrain in question and more focused on sifting the gold from the dross, much in the way of any modern social media system.

Both AllTrails and FatMap are emblematic of a new breed of what we might call deep-content mapping apps,which shift the focus away from using maps as tools for that central ritual of plotting and planning and toward an on-the-spot depth of data. How we plot and plan will differ from user to user. Although many folks prefer the simple, almost analog feel of the CalTopo interface, others prefer Gaia GPS, which merges different map-overlay features—for instance, toggling between the original USGS quad and an updated digital rendering of the landscape—with a brighter, moremodern graphic and cleaner, less cluttered interface. While I’d recommend Gaia to a new hiker for its intuitive use and ease of setting up GPS tracks, I would instead suggest CalTopo for an old-school, AMC White Mountain Guide-toting backpacker just now starting to take a smartphone into the backcountry. And, while Gaia moves seamlessly from desktop or laptop to use on a smartphone at a trail junction at dusk, CalTopo’s smartphone interface isn’t quite there, and linking ageospatial PDF to Avenza is the best option.

As adventurers choose software to plan new trips and re-travel known paths, we need to think critically about how we are reestablishing our habits in a mapping world that has gone far beyond simply collating our entire White Mountain Guide map set in digital form. Living with the new breed of deep-content apps, we run the risk of under-preparation by shortcutting the established ritual of planning a route in advance. More than that, we risk circumscribing our understanding of traveling in the mountains, basing our actions not on our own breadth of creativity but on the deep specifics of an app’s recommended trail, ridge, or ski line. By putting our navigational powers in the hands of the app, we risk turning our maps back into squares whose edges, literal or figurative, we will inevitably reach.

*Tam McTavish, “Gear Review: 3 Best GPS Map Apps,”, February 21, 2021.