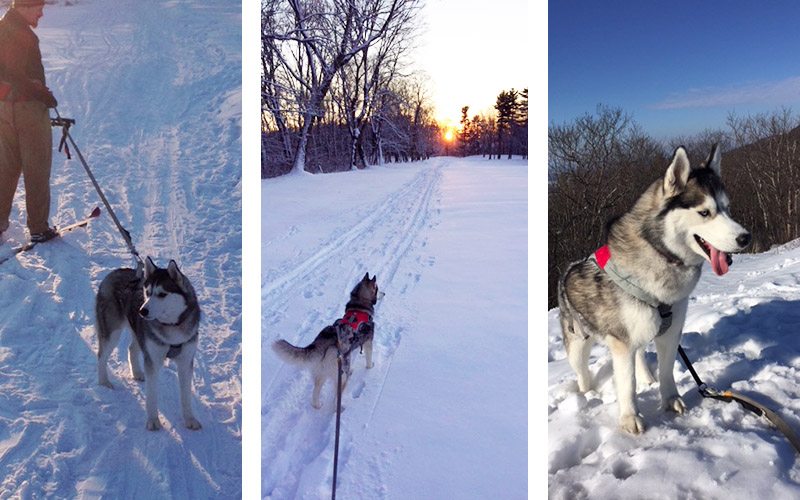

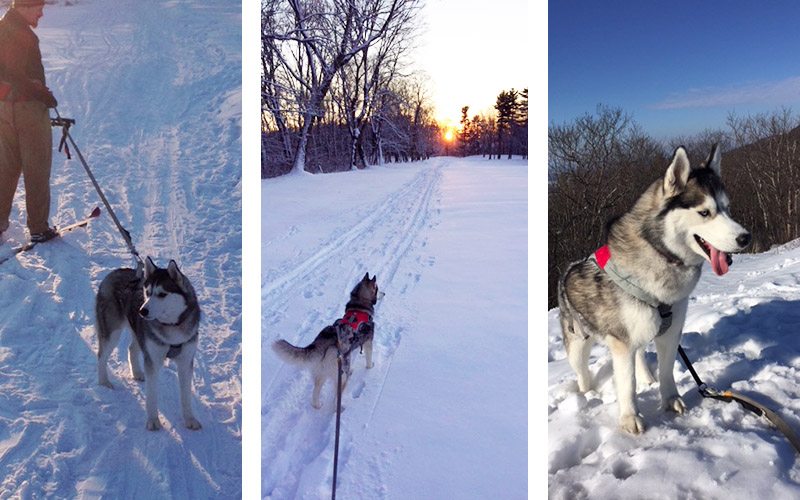

Skiing with dogs doesn’t require a predawn start, but the author and Togo (above) like to get their skijoring runs in early.

Before I could say, “Yip yip,” Togo dashed down the trail, plunging through half a foot of fresh powder and pulling me along behind her. As we made our way into the woods, my grin increased in keeping with our pace.

The switchback mountain-bike trail outside Northampton, Mass., descended slightly but consistently, with gravity giving Togo a hand. At first, I tried to stride my skis in pace with her, as we do on flatter terrain. But as we whipped around one turn and darted down another in conditions far better than usual, I switched techniques. Widening my stance, I leaned back and enjoyed the ride. For several minutes, it felt like I was waterskiing through the snow—the best ski day of the season. What I sacrificed in cardio-vascular gain, I more than made up for in pure experiential thrill.

A lifelong downhill and cross-country skier, I thought skijoring seemed like a natural extension after adopting a Siberian husky, the breed most likely to take off on a multihour walkabout at any given moment. These days, I spend most of my ski time skijoring. For those not familiar with the activity, a long leash connects me via a waste belt to my dog, who is wearing a harness. What might sound like an added challenge is actually a great way to experience the winter months. If you can cross-country ski and you have a willing canine collaborator, you can skijor. But as with all outdoor pursuits, there’s varied gear, training strategies, and techniques to consider.

“It’s an easy sport to get into,” says Meg Mizzoni, the president of the New England Sled Dog Club (NESDC). Founded in 1924, the NESDC is the oldest club of its kind in North America and one of several organizations in the Northeast—including the Yankee Siberian Husky Club, the Down East Sled Dog Club, and the Pennsylvania Sled Dog Club—that host races in the winter, weather permitting.

Although Mizzoni doesn’t compete in skijoring races, she does practice the sport regularly. “Not everyone can have twenty dogs,” she says, “but one or two is enough to skijor.”

But let’s not put the cart before the horse—er, the leash before the dog. I’ve never entered a skijor race, and yet each year I look forward to skijoring on a variety of terrain, from old logging roads to groomed trails on golf courses and even paved sidewalks buried under the recent accumulation of a wicked winter storm. And in the four years since I brought her home as a puppy, Togo has never lacked in skijor enthusiasm—which can be particularly helpful when I need extra motivation.

CHOOSE YOUR DOG

Sled dogs, such as Siberian huskies, or hounds, such as German shorthaired pointers, may display a more natural tendency to pull, but any dog can be trained to skijor. “You need a dog that’s going to stay in front of you,” Mizzoni says. “Getting them used to being on a leash is key.”

Working with your dog year-round is essential. When we can’t ski, I trail run—called “canicross” by dog drivers—with Togo’s leash in hand. Wrapping the leash around your waist will work, too. Ideally, your dog will keep the leash taught without pulling harder or faster than you can go. A slack leash can lead (no pun intended) to extra challenges, like tripping over the line. This can be especially problematic when strapped into skis.

Bikejoring, in which the dog’s leash is clipped to an attachment on your bike, is another popular shoulder-season regimen. “Hydration is key,” says Mizzoni—for humans and canines, both.

CHOOSE YOUR GEAR

To get started, you’ll need a sturdy harness, a waste belt, and a leash. Many companies offer extensive choices of all three. But those who aren’t competing can use gear not specifically designed for skijoring. I once came across a guy skijoring in his rock-climbing harness.

The ideal leash will have some stretch, like a bungee cord, to absorb shock and lessen the harsh yank your dog feels when transitioning from stop to go. Your waste belt should include a mechanism that allows the leash to attach and detach easily and quickly, in case you find yourself being pulled in a dangerous direction. Mine is equipped with a plastic clip that I can open to release and let Togo pull her leash from my belt.

During the warmer months, I put Togo in a regular harness, clipping the leash at her shoulders. In the winter, I use a skijor harness, which is sturdier and has a leash-attachment point near her hips. This puts greater distance between Togo and my skis while still harnessing her complete pulling capacity.

While competitive skijor practitioners use skate skis for speed, cross-country skis are usually fine. Avoid skis with metal edges, which can cut your dog if the two of you accidentally collide, which, for newbies, is a possibility. Best to be cautious.

CHOOSE YOUR TRAIL

Assessing trail conditions—which can change quickly, especially here in the Northeast—before you head out is essential.

“Be aware of crusty trails, which can hurt your dog’s feet,” Mizzoni says. If you are giving your dog a more strenuous workout over rough terrain, or if you notice your dog tending to her paws upon arriving home, you may want use a balm or canine booties. (Full disclosure: I have yet to use these.)

Groomed trails, such as those on golf courses and other recreation areas, usually offer the best conditions, not to mention the best opportunity to strenuously stride your skis behind your dog. Races are always held on groomed trails, Mizzoni notes. Logging roads and hiking trails have less reliable conditions and can include hazards hidden by the snow, such as trees and rocks. Not all groomed trails accept dogs, so be sure to call ahead.

In the summer, I choose a path alongside a pond or a stream shaded by trees. I also rotate routes, so that Togo smells something different from one excursion to the next.

Smell trails are just one means of motivation. “You need to make [skijoring] a positive experience for them, so the dogs want to do it,” Mizzoni says. Other types of encouragement include edible treats; meeting up with another dog, depending on the nature of your particular canine; and ample praise.

Vocal commands are also helpful, especially when racing. Most dog drivers use “Gee” (right), “Haw” (left), and “On by” (pass the team in front of you). I use “Yip yip” (go), the command Aang gave his flying bison, Appa, in the TV series Avatar: The Last Airbender, and the standard “Whoa” (slow), while affecting a low, cowboylike drawl.

“On a fast trail, the dogs need to slow down, or they’ll burn out,” Mizzoni says. “On a punchy trail, where their feet are sinking through [the snow], go slower. When going uphill, keep talking to them. Don’t encourage stopping.”

Controlling your speed, and adjusting your expectations, is essential. A week after Togo and I enjoyed that impeccable powdery day, the same trail had morphed into icy hardpack. Skijoring was difficult, if not dangerous. So we hiked, instead, up an ice-free ridge for an above-treeline overlook.

Whatever route you choose and, skijoring is about exploring the wintry landscape with your dog. “Working with the dogs is really rewarding,” Mizzoni says. I always return home rejuvenated and refreshed, physically spent and emotionally satisfied. And the more Togo and I work in tandem, the greater the variety of trails and terrain we can travel together.

LEARN MORE: 5 BASIC TIPS FOR SKIJORING BEGINNERS

1. Contact a club for information on classes and recommended sites for skijoring.

- New England Sled Dog Club: New England’s oldest, formed in 1924

- Yankee Siberian Husky Club: Formed in 1968; membership is New England-wide

- Pennsylvania Sled Dog Club: Based in Pennsylvania since 1971, although membership extends to surrounding areas

- Lakes Region Sled Dog Club: A spinoff of the Laconia Sled Dog Club, formed in New Hampshire in the wake of the 1925 Serun Run to Nome, Alaska, which introduced dogsledding to the greater public

- Down East Sled Dog Club: Based in Maine

2. Get the gear. There are many skijor outfitters; below are a few to get you started.

- Nooksack Racing Supply: Based in Oxford, Maine

- Howling Dog Alaska: Based in Leavenworth, Kansas

- Ruffwear: Based in Bend, Oregon

3. Set your expectations low. It’s much easier to run after learning to walk. Similarly, it’s much easier to skijor after cross-country skiing. Likewise, skijoring on flatter, smoother terrain is easier than starting off on a wooded hillside.

4. Be mindful of your dog. Even dogs who like to pull may need to get accustomed to the feeling. Tie them to an old tire and have them pull that around before tethering yourself to your dog. As your dog gets used to the arrangement, increase the amount of time your work together.

5. Keep reading. I recommend the following resources.

- Skijor with Your Dog, Second Edition (University of Alaska Press, 2012), by Mari Høe-Raitto and Carol Kaynor

- Ski Spot Run: The Enchanting World of Skijoring and Related Dog-Powered Sports (KISATI Ventures, 2004), by Matt Haakenstad

- Skijor USA: Based in Minnesota, this organization is advocating for skijoring to become an Olympic sport

- Sled Dog Central: A nationwide community forum for winter dog sports

- United States Federation of Sled Dog Sports: The national governing body of sled-dog sports