Fire lookout Barbara Mortensen carries wood to her Pine Mountain, New Hampshire tower.

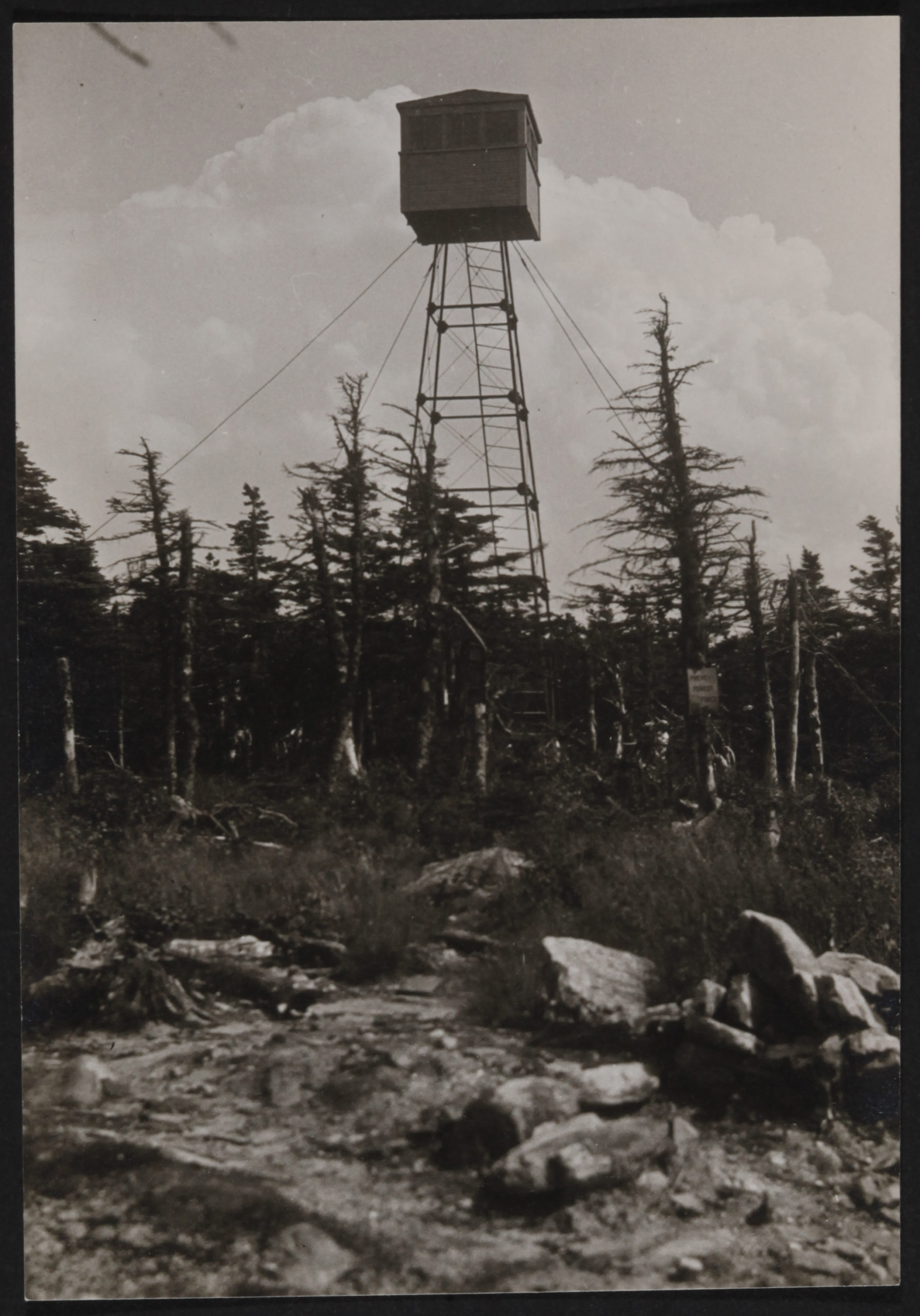

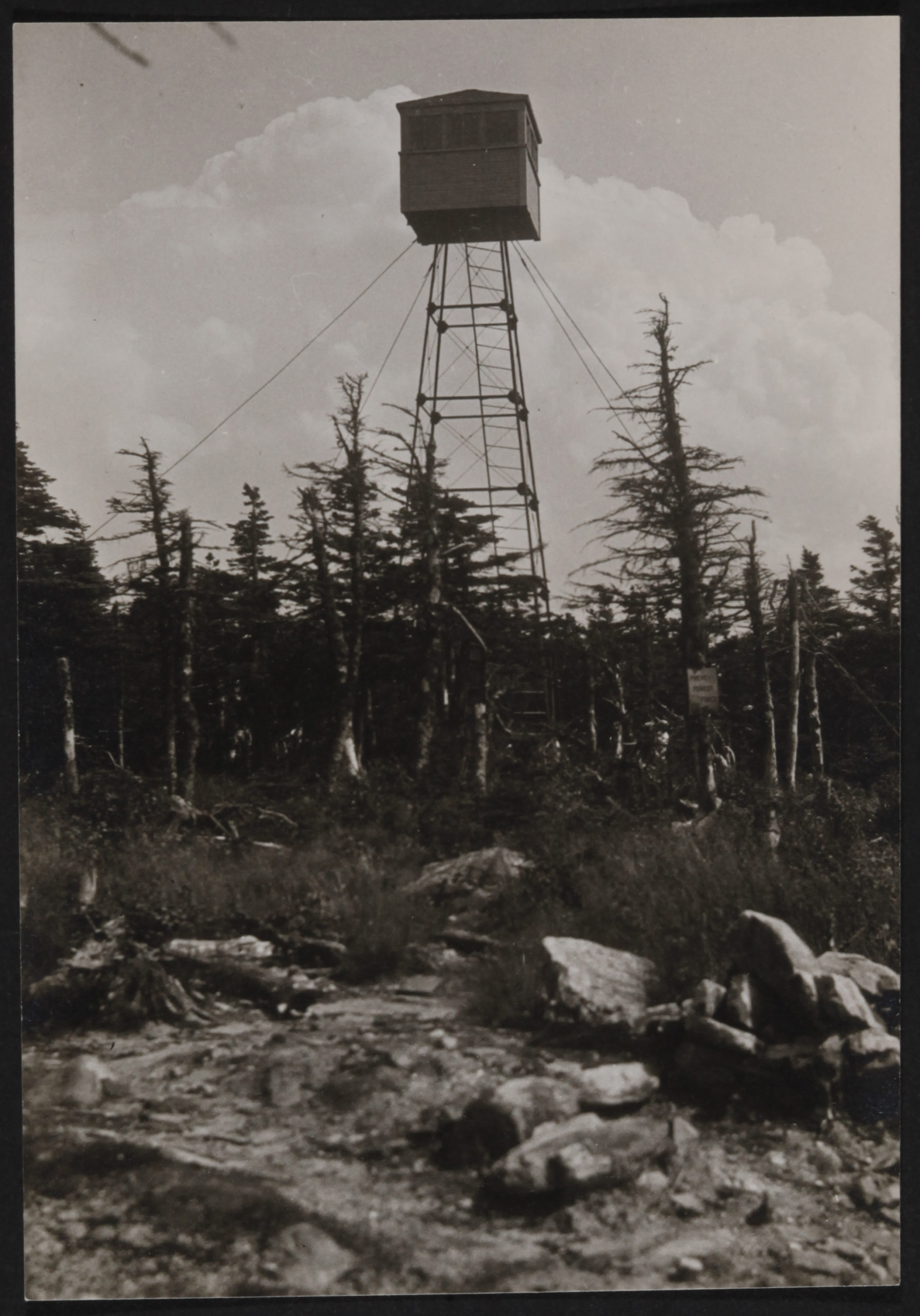

Forest fire lookout towers are a common feature of mountain summits here in the Northeast. Made up of a cement base with a wooden compartment above it on stilts, with a ladder or stairs leading to the top, it provides 360-degree views of the surrounding area. Sometimes hikers can climb to the top and take in that view, but many times the towers are blocked off for safety purposes or only the cement base remains.

It wasn’t too long ago, however, that these structures were an essential part of forest management, giving hired lookouts a vantage point to quickly spot forest fires and radio or telephone down the mountain, potentially saving lives and land from burning. The work was physically challenging and typically solitary, with lookouts working for months at a time and often going for extended periods without human interaction.

And almost from the beginning, many of these lookouts were women.

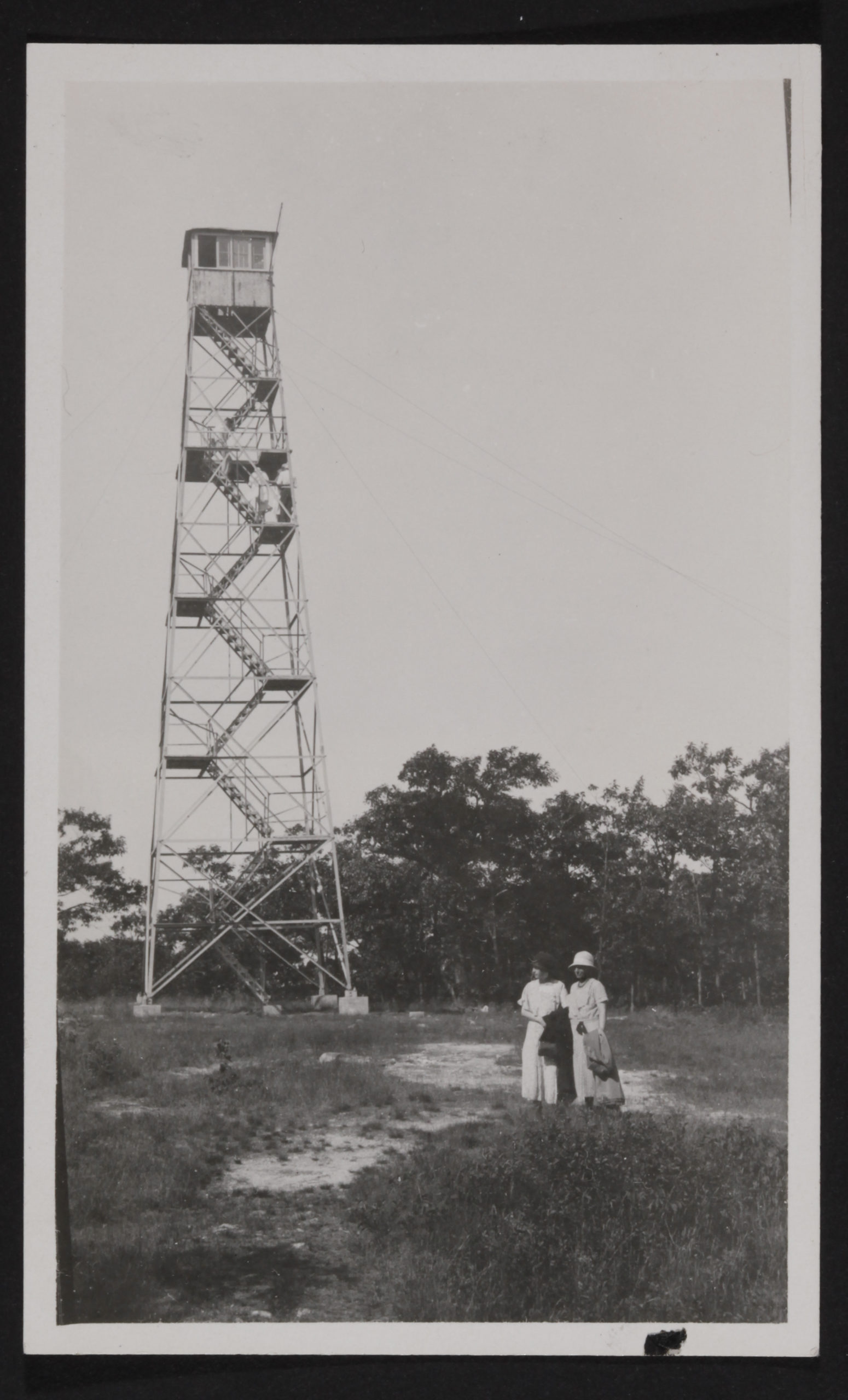

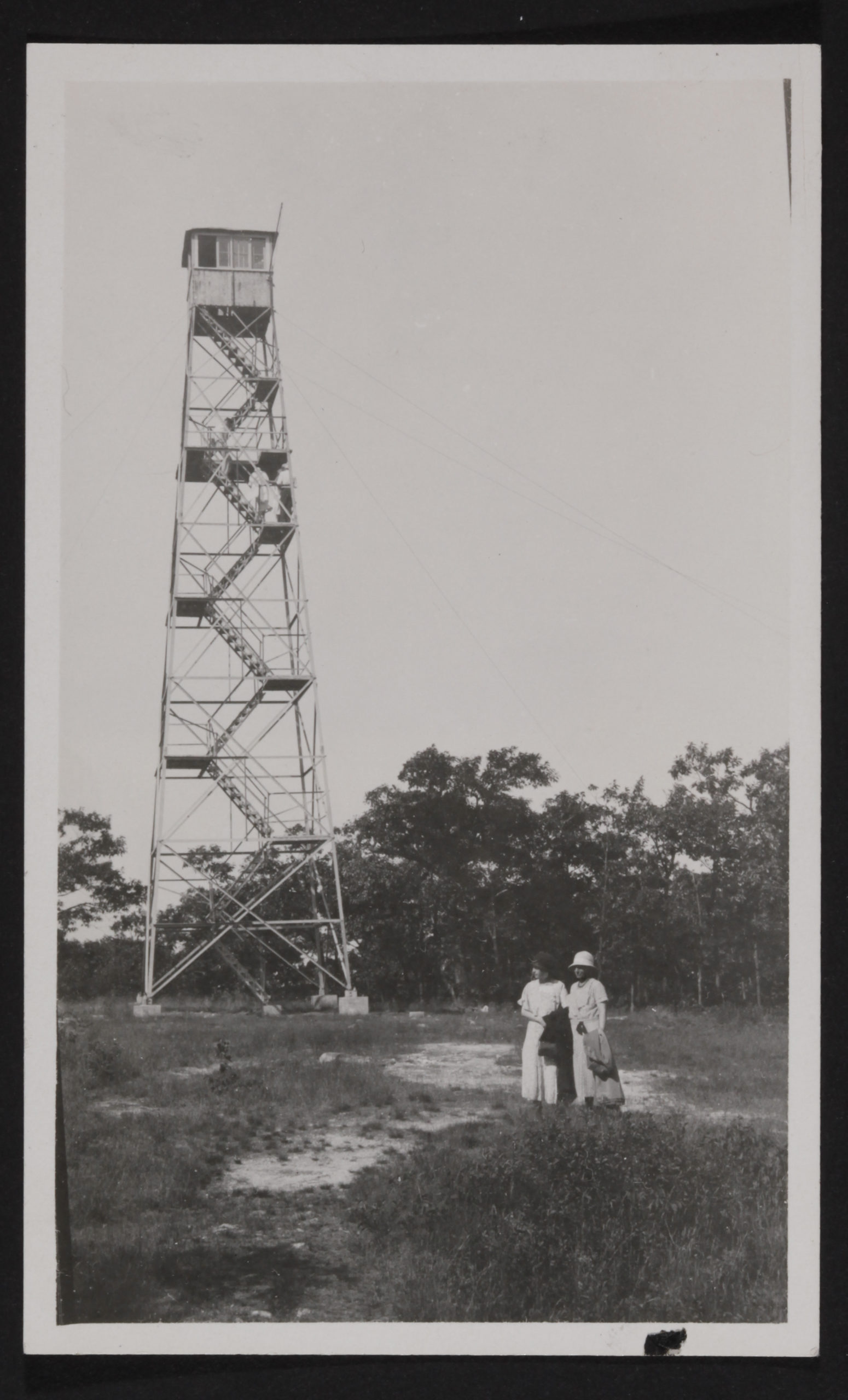

Two women stand in front of a fire tower at the summit of Mount Uncanoonuc in New Hampshire in the 1920s.

America’s First Fire Towers

While a few fire watch towers had been around since the late 1800s, construction projects nationwide ramped up following the “Big Blowup” of 1910, a series of devasting forest fires that burned down about 3 million acres across Idaho, Montana, and Washington state. In response to the tragedy, the U.S. Forest Service set aside funding to build new towers and hire lookouts as federal employees. Within a few years there were hundreds of towers across the country including 26 lookout stations in New Hampshire alone in 1913, according to the Conway Daily Sun.

It wasn’t long before women began serving in this new role, both out west and in New England. In 1913, Hallie Morse Daggett became the very first fire lookout employed by the U.S. Forest Service—trekking up to Eddy Gulch, in California’s Klamath National Forest for that season. Although Daggett was initially met with skepticism by many higher ups in the Forest Service (her supervisor had to write a letter defending his decision to hire her, in which he called it a “novelty.”), she quickly proved her mettle, preventing several fires in her first year then returning for another 14 seasons.

With the precedent set by Daggett, a small but growing number of women lookouts began to stake their claim to the job. In 1918, a 21-year-old named Alice Henderson became Mount Kineo’s, and New England’s, first female lookout. According to a Daily Kennebec Journal article from the time, Henderson told the forest commissioner who interviewed her that she could “do the work as well as any man.”

Mortensen, accompanied by her dog, Brenda, watches the mountains. The number of women hired as fire lookouts in the White Mountains increased during the World War II years.

“Lady Lookouts” in the White Mountains

During World War II, with so many men away for the war effort, women were encouraged to take on jobs that had previously not been available to them. While many women assumed the factory jobs previously held by their husbands, manufacturing the equipment and weapons used overseas, the boost to women’s employment extended to outdoor spaces, like game warden and forest fire fighter roles. Women also began applying for fire observer positions in increasing numbers.

The Appalachian Mountain Club did its part. In a 1943 Appalachia Bulletin, club president Irving Meredith put out a “challenge to club members”:

Owing to the current shortage of manpower, it is probable that it may be necessary to have women “man” the fire lookout towers in the White Mountain National Forest this summer. Mr. Graham, the United States Forest Supervisor, has asked the cooperation of the [Appalachian Mountain] Club in recruiting a group of women for this purpose…

The job is not an easy one, but anyone undertaking it will have the satisfaction that she is helping protect the natural resources and the beauty of a region we all love.

The new, female generation of lookouts in the White Mountains were called WOOFS, an acronym for either Women Observers on the Forest or Women Observers of Fire Towers. The term was most likely coined by a local newspaper, rather than any of the women themselves, according to the Conway Daily Sun.

Fire towers in the 1920s were usually made up of a roofed cabin or room atop a staircase. Today, you can still climb some fire towers (be sure to read all signs to make sure it’s allowed) and get spectacular views of the surrounding region.

A Day in the Life

Many of the conditions, routine, and chores of a forest fire lookout during the World War II probably wouldn’t have looked too different from what today’s AMC Hut Caretakers experience. Days began with a series of chores like cutting firewood, followed by long hours of observing the surrounding area and recording weather and fire risk. Lookouts were trained in skills like radio communication, orienteering, and the highest risk weather patterns for a fire.

Pay was limited and, in many cases, lookouts were required to purchase and pack-in their own food. According to New Hampshire fire tower historian Iris Baird, one local market would leave Barbera Mortensen, a WOOFS at the Pine Mountain lookout near Gorham, N.H., free food and cigarettes under the business’s stairs.

While the work was solitary, women observers weren’t alone for the entire stretch of the season. Lookouts were permitted to have overnight visitors, typically other women, and interacted with passing hikers. Mortensen even had her 105-pound Great Dane, Brenda, to keep her company.

In addition to continuing the traditional work of a lookout, women during World War II took on one new responsibility: keeping an eye out for potential enemy aircraft.

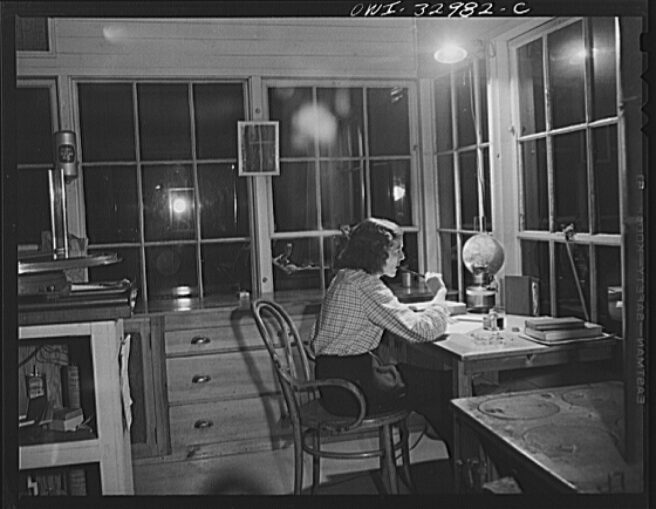

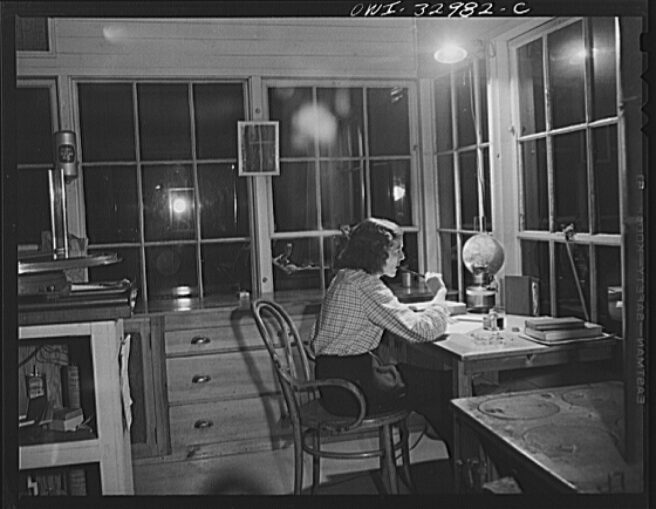

Mortensen at her desk at night. Although the work of a lookout was mostly solitary, many did have friends and family stay as guests.

Forest Lookouts Today

While the World War II years may have been a golden age for women fire lookouts in the White Mountains, it was also the beginning of the end for the profession in much of the Northeast. Following the war, the Forest Service began using aircraft to spot forest fires—covering large areas in a short period time, although still not offering the round-the-clock coverage that a lookout could. Despite the shortcomings, the forest service began phasing out many of the lookout towers and hiring fewer observers with each passing season.

Although the forest fire observer has faded from prominence, it’s still a seasonal position, especially in parts of the West. In 2012, Nancy Hood became the longest serving fire lookout of any gender in Forest Service history. Hood did most of her 55 years of service in the Klamath National Forest, the same area where Hallie Morse Daggett was first hired more than a century earlier.

Today, many towers in the Northeast remain in good condition. The Mount Kineo lookout tower in Maine, as well another tower on nearby Big Moose Mountain, are still standing. In the White Mountain region, hikers can spot towers at the summits of Mount Kearsarge, Mount Cardigan, Milan Hill, as well as Mount Magalloway in Coos County.