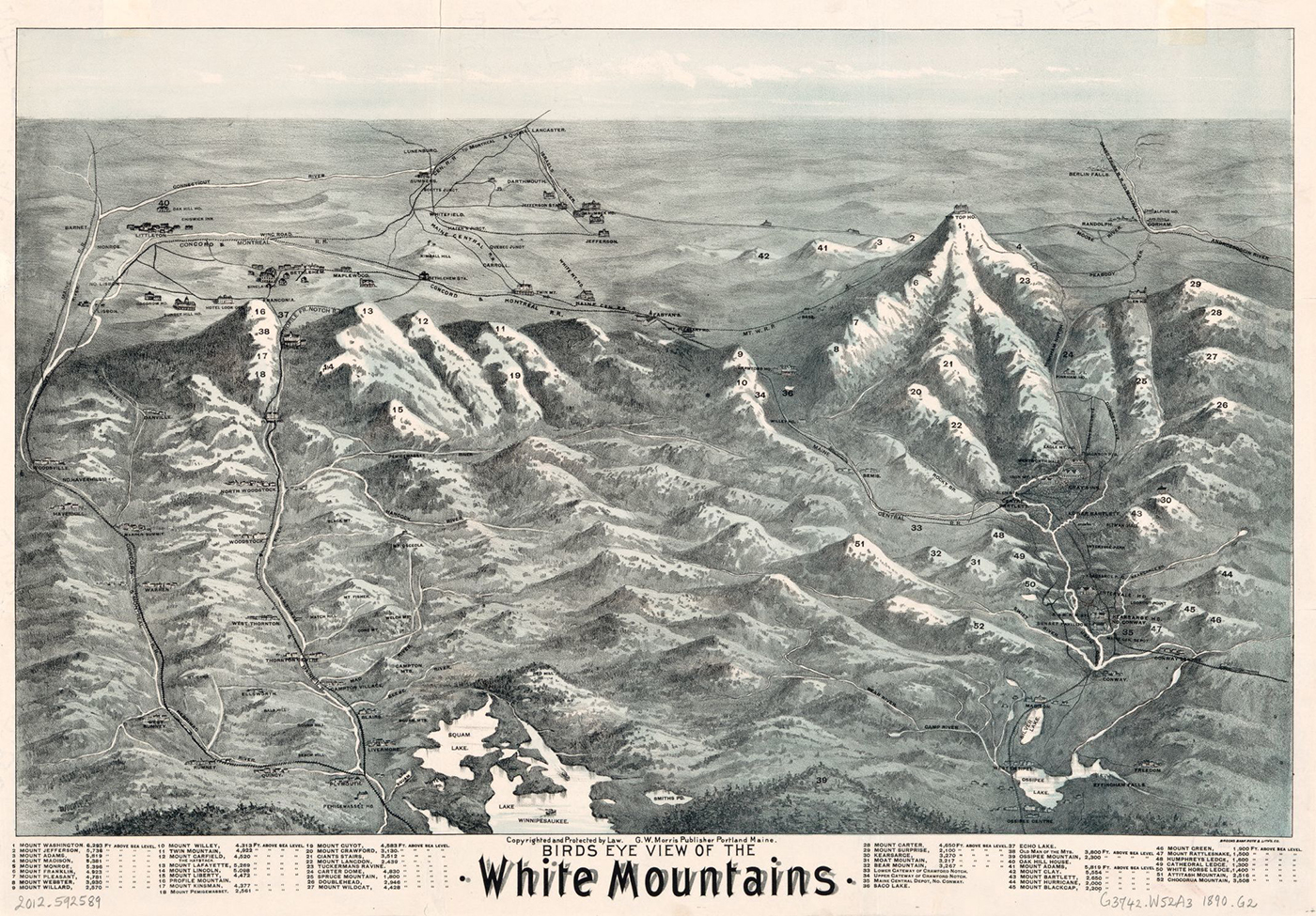

A G.W. Morris map from the 1890s shows a bird’s-eye view of the White Mountains, where wayfinding and backpacking at the time was quite different than it is today.

The following is a sneak peek at one of the presentations scheduled for AMC’s 146th Annual Summit. Summit gives members of the AMC community a chance to hear from outdoor experts, honor volunteers and sit in on AMC’s annual business meeting.

This year’s event will be held virtually on Saturday January 22, 2022. To learn more and register please visit: https://www.outdoors.org/summit/

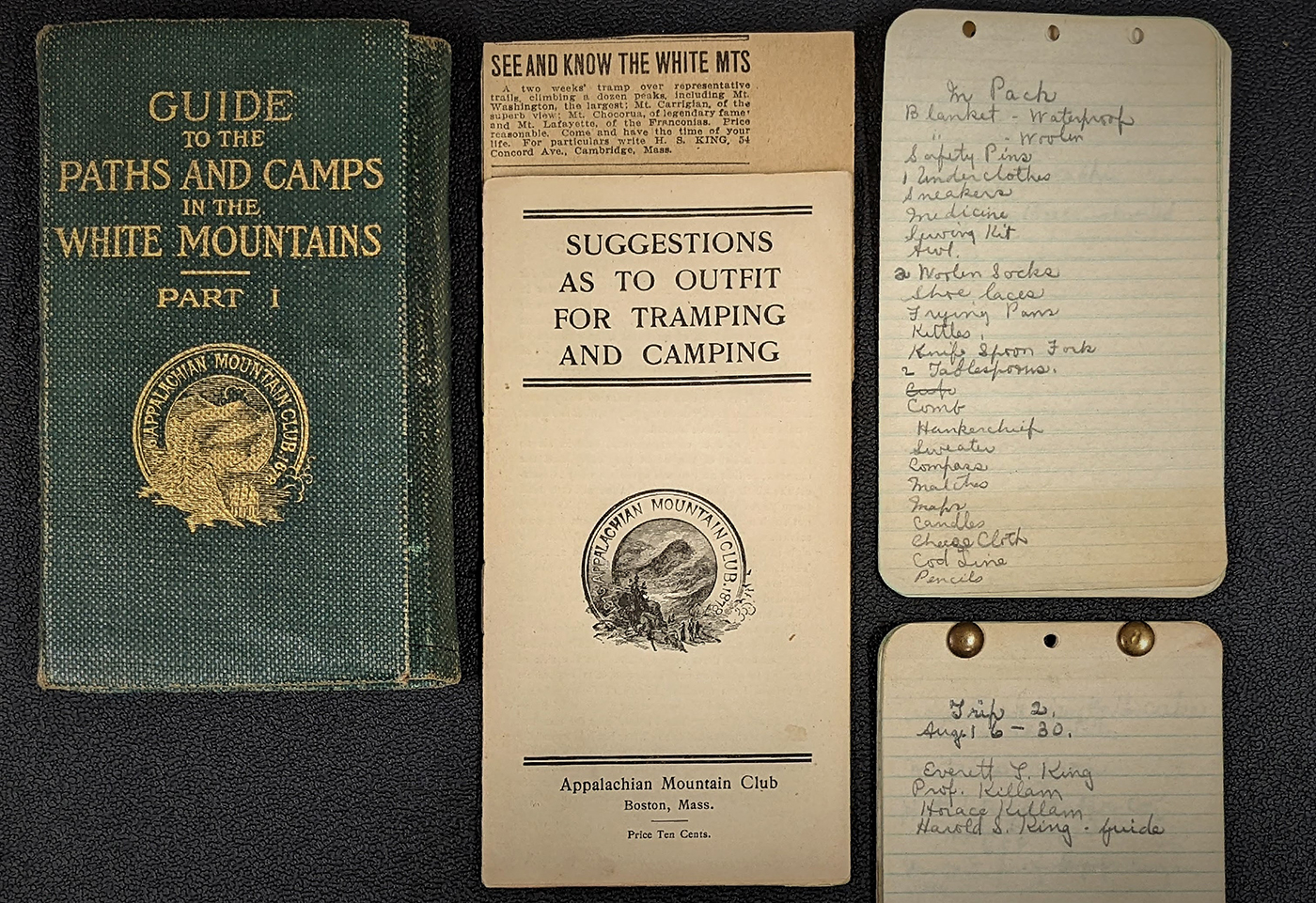

Have you ever tried to retrace the steps of an explorer from before your time? Attempted to use an old map to guide you around a modern landscape? AMC Archivist Becky Fullerton has been sifting through early 20th century hiker journal excerpts and historical and contemporary photos and maps from the White Mountains to determine how wayfinding and backpacking have changed over the past century or more—and how they’re exactly the same. Fullerton will share these journals, old maps, and photos—as well as her thoughts on what we can learn from these early adventurers—in a 2022 AMC Annual Summit session titled, “Wayfinding: Historical Journals, Maps, and Hikers of the Pemigewasset Wilderness.”

We sat down with Fullerton to learn more about what drew her to the topic of wayfinding and what Summit attendees can expect in her session.

AMC Archivist Becky Fullerton pored over century-old maps and hiker journals to analyze how wayfinding and backpacking has changed—and how it’s the same.

How did you land on the topic of maps and wayfinding?

I’m not a map expert, but I have an appreciation for maps and people who make maps—particularly from the 19th century and earlier, where they were doing this all fresh. You don’t have GPS. You don’t have aerial photography. You must physically go out on the land and explore and find some way to make sense of where you are and what you’re looking at. In the AMC Archives we also have a lot of handwritten journals with the recorded words, thoughts, and feelings of early hikers. Some of the journals describe walking in places where there aren’t established trails, so you’re trying to figure out where they are on the map. Here are these people who wrote about this trip they took, and we can look at maps made around the time they were hiking and try to determine where they were and how it compares to what the landscape looks like now.

Plumes of smoke from the 1907 Owl’s Head fire at the head of the Franconia Brook Trail as seen from a logging camp miles away.

The terrain of the White Mountains has changed pretty significantly from then to now, right?

Yes, it has. For example, there are lots of instances [in the journals] where they’re walking through landscapes that were, at the time, being cut over by logging operations or recently burned in a forest fire. It’s starkly different from what we see today, especially in the White Mountain National Forest, where it’s just this solid green carpet. It’s hard to imagine charred trees all around us, walking through a logging cap, or finding these little pockets of civilization in the forest. I find that really fascinating.

Hikers take a rest in their Pemigewasset Wilderness camp site in around 1910.

How has wayfinding and backpacking changed since the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and how is it the same?

The gear has changed quite a lot, of course. But from reading these journals and accounts of people’s trips—especially when they’re venturing into the wilderness to find a new route—a lot of their knowledge about where they’re going is based on word of mouth or looking at very general maps, if there are any. They tended to follow landmarks like rivers or a ridgeline, and oftentimes hired a local guide who knew the area because they had hunted or fished there. There’s an element of adventure I don’t think we see quite as much anymore. Today the trails are so well established, you can (and should) read ahead about exactly where you’re going and what the conditions are like. You can go on the Web and find out exactly how muddy or icy the trail is. So much information is out there. At the same time, if you’re going somewhere you’ve never explored before, there’s still room for a feeling of discovery.

Hikers rest in the krummholz along the abandoned route of the Old Bridal Path on Mount Lafayette in 1920.

Can you give us a preview of one journal entry that has stayed with you?

There is a segment I talk about in this lecture from a trip taken in 1882 by AMC’s supervisor of trails. He advertised that he was going to cross the Pemigewasset Wilderness, which at the time was still pretty much trailless. He didn’t get any interest except from three women who signed up to go with him. At first, he thought, “I’m not completely sure about bringing ladies into this vast, trailless wilderness, but if they’re willing to go then let’s do this.” He hired a couple of guides, and led the party over North Twin, the Bonds, all the way through the wilderness, and they popped out at the Crawford House site days later. It was almost entirely bushwhacking. They really weren’t on trails. But what struck me is that climbing North Twin Mountain the first day, they had to bushwhack through about a mile of krummholz—these gnarly, short spruce trees. You walk up a trail now, and it’s all cleared out, but this party was forcing their way through this dense mass of krummholz, being scratched and grabbed at by limbs for hours. It just blows my mind that they would do these things. A trail was eventually cut based on their explorations, but they had to go through this incredible trial first.