This story was originally published in the Winter/Spring 2021 issue of Appalachia Journal.

For some a single ascent of a rock wall is challenging enough, but others choose to push further.

At a secluded crag near my house, there’s a climbing route called Malevolent Eye. It’s 32 feet high, with a 3-foot overhang and a difficulty rating of 5.10–. It’s tricky enough to challenge a good climber, with several blade-thin holds and a slippery, insecure lunge in the middle.

A couple of decades ago, the prolific Connecticut climber and guidebook author Ken Nichols ascended Malevolent Eye 50 times in one day. His record stood unchallenged until early 2020, when a mutual friend of ours—Brian Ludovici, then an undergraduate at the University of Connecticut and president of its climbing club—climbed it 70 times in a day. When I heard, I told Nichols—who is in his early 70s and still climbs religiously—that I wanted to try to set a new record and possibly break 100.

Connecticut doesn’t boast the soaring cliffs of New Hampshire and Maine, so climbers here have to get creative to do long routes.

Connecticut doesn’t boast the soaring cliffs of New Hampshire and Maine, so climbers here have to get creative to do long routes —especially when outdoors areas are closed because of a new coronavirus. The American Alpine Club in March discouraged climbers from visiting cliffs so as to not spread the virus, while New Hampshire’s sport climbing area of Rumney and New York’s Shawangunk Ridge altogether closed. But under controlled conditions at local crags where social distancing is the norm, climbing in small groups appeared to be in keeping with the Connecticut’s governor’s executive order that “individuals should limit outdoor recreational activities to non-contact and avoid activities where they come in close contact with other people.”

Still, he loved the idea of a competition developing around who could do the most ascents of Malevolent Eye.

Nichols was skeptical of my goal for Malevolent Eye. I’d fallen repeatedly when first trying the route two years ago and since then had only managed ten ascents in a day. My wife, Jenna, and I had recently had a baby, a fact that earned me endless ribbing from Nichols that my climbing days were numbered. Still, he loved the idea of a competition developing around who could do the most ascents of Malevolent Eye. Since he was recovering from a shoulder injury and couldn’t climb himself, he volunteered to belay me for the effort—while of course maintaining a six-foot social distance.

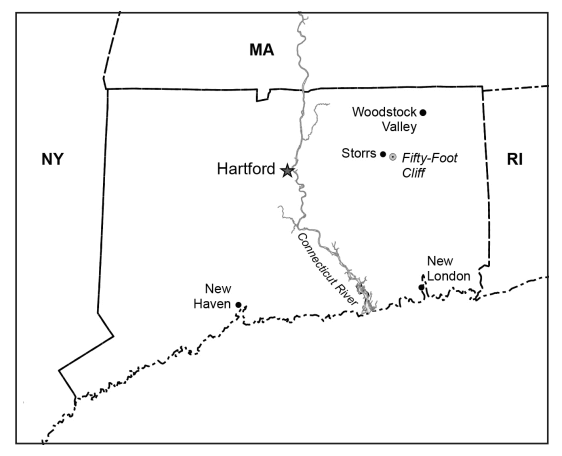

Stephen Kurczy’s objective, Malevolent Eye, is a route on the Fifty-Foot Cliff near the University of Connecticut, in the Storrs section of Mansfield, Connecticut.

I started climbing at 8 a.m., feeling infinitely far from 100.

On a cool morning in early April, we hiked the half-mile into Husky Rock (so named because nearby University of Connecticut’s mascot is a husky), tied an anchor around a tree at the top of the cliff, and hung a static rope. I had a coffee canteen. Nichols had his peanut M&Ms. We were prepared to be there all day.

I started climbing at 8 a.m., feeling infinitely far from 100. My plan was to do reps of five, with a five-minute rest between sets. The climbing sequence went like this: Side pull with left hand, high crimp with right hand, step feet onto blade-thin edges, bump right hand to higher crimp, cross left hand over right hand to medium pocket, match hands, shuffle feet, bump hands up to deep pocket, shuffle feet, move left hand up to a rounded and downward sloping hold, high step right foot, bump right hand to the “malevolent eye”sloping hold and then to a deep pocket for a hand jam. Shake out. Reach high, reach high, reach high again, and mantel to a stance on the cliff top.

I kept a tally with rows of stones so I wouldn’t lose count of my total. The first three hours I averaged 20 ascents per hour, falling for the first time as I was about to surpass Nichols’s record. He promptly lowered me to the ground, as per his rules of climbing: The ascent only counted if I didn’t fall. There would be no hangdogging. By 11 a.m. I had finished 60 reps. I gave myself a half-hour rest.

The temperature was in the 60s with full sun. My fingers were pink and burning. My head felt foggy, partly from the climbing but also from sleep deprivation, having been kept awake the previous night by a crying baby. I lay on the ground and closed my eyes.

People who run around a city block 5,649 times (or who endlessly climb Malevolent Eye) “are driven by something more secular than spirituality—they could be hungry for meaning, in general.”

What was propelling me onward? It seems absurd to suggest I was climbing for the “glory,” as who cares how many times an obscure, short cliff in the boondocks of Connecticut has been top-roped? There’s an arbitrariness to all athletic “achievements,” be it sprinting in a circle or running 26.2 miles, hitting a ball over a net or throwing one into a 10-foot-high hoop. And what I was doing was nothing compared with the monotonous pointlessness of the Sri Chinmoy Self- Transcendence 3,100 Mile Race, which consists of 5,649 laps around a city block in Queens, New York. What motivates humans to such endeavors? They drive “people to persevere through unpleasantness in the hope of grander rewards in the distant future,” social psychologist Adam Alter wrote in a 2015 essay on long-distance runners in The New Yorker. People who run around a city block 5,649 times (or who endlessly climb Malevolent Eye) “are driven by something more secular than spirituality—they could be hungry for meaning, in general.”

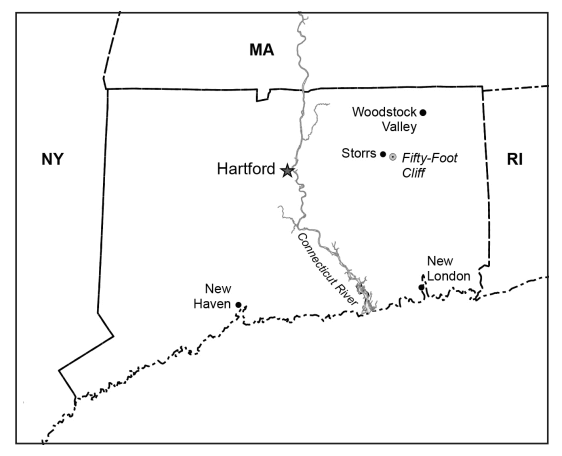

Ken Nichols, grinning, was Stephen Kurczy’s support for most of the day. Below him, the stones that recorded each climb.

Once I got there, my goal became to hit 122, which was the personal single- day record for Nichols—and in all likelihood the all-time single-day ascent record for any cliff in the Northeast.

My new goal was to do 110 reps, which sounded like a nice round number. Once I got there, my goal became to hit 122, which was the personal single- day record for Nichols—and in all likelihood the all-time single-day ascent record for any cliff in the Northeast, he said. Because who else in their right mind does stuff like this?

Just as I topped the cliff for number 122, Nichols reappeared. It was as if the momentousness of my surpassing his record had conjured him back. He retook the belay from Shah, who headed home for dinner. I popped two more ibuprofen with fresh water. My fingertips had gone numb. My hands were bleeding. An oozing rash appeared near my wrist from repeatedly doing a hand jam. I had also memorized the route so completely that I felt totally confident in ascending, save for one move toward the start. Before each ascent, I would tell myself two things: “It’s just one move,” and, “My fingers are pillows,” as a way of convincing myself to ignore the pain in my fingers. The recitations became my mantras.

Now my goal was 130. Then 140, which would double the previous record. Once I got to 140, I figured I might as well round up to 150. Nichols was periodically breaking into chuckles. As I approached 150, he suggested a few more. “If you climb it 157 times, you’ll have done more than 5,000 feet of climbing!” he said.

It was now 6 p.m. All I’d eaten that day were two pieces of toast, a chocolate bar, a Clif bar, an apple, and some Goldfish crackers. I was exhausted. I wanted to be done. I stared at the ground.

“You’re so close to 5,000 feet,” Nichols said. “Why not just do seven more?”

When I hit 157, I figured I might as well do another three to reach an even number. As I neared number 160, Nichols moved the bar again. He was scribbling numbers on a piece of paper.

“Steve, I am not kidding,” he said, “but I did the math and if you climb 165 times it would be exactly 5,280 feet—a vertical mile!”

As much as I was ready to be done, I was charmed by Nichols’s enthusiasm. He’d been belaying me all day, fueling me with chocolate, refilling my water, and giving constant encouragement—despite the fact that I was trying to break his old records.

“You just have to do 165!” Nichols said. “It’s too perfect. And then, I promise, I won’t egg you on anymore.”

I’d climbed the equivalent of both The Nose of El Capitan and Half Dome in Yosemite in a day.

When I completed the 165th ascent, Nichols dubbed me a new inductee of the Mile-High Club—I don’t think he realized “mile-high club” is slang for people who have sex on airplanes. I’d climbed the equivalent of both The Nose of El Capitan and Half Dome in Yosemite in a day. We turned back-to-back and elbow-bumped. I arranged my 165th stone on the ground.

Climbing Malevolent Eye 165 times was absurd, a trivial repetition of human movement. But isn’t this how life in general can feel, perhaps especially amid self-quarantining and a pandemic?

Climbing Malevolent Eye 165 times was absurd, a trivial repetition of human movement. But isn’t this how life in general can feel, perhaps especially amid self-quarantining and a pandemic? Hit the alarm clock, drink coffee, log online for work, walk to the table for dinner, climb back into bed, repeat. Life is a series of repetitions that can feel like an endless loop.

But by embracing life and putting a shoulder to the boulder, I can create meaning.

But in the words of the philosopher Albert Camus, meaning comes from embracing the absurd. This theme is at the heart of his philosophical essay, “The Myth of Sisyphus.” In Greek mythology, Sisyphus was condemned by the gods to repeatedly roll a boulder up a hill. Camus argues each human lives a kind of Sisyphean life. But by embracing life and putting a shoulder to the boulder, I can create meaning. “Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world,” Camus wrote. “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

It was dusk as Nichols and I coiled the ropes and walked back to our cars. I got home at 8 p.m. Jenna shook her head when I recounted my day. “It sounds

like a hot dog eating contest,” she said of my endeavor on Malevolent Eye.

My hands were so red and raw they felt like they were burning when I ran them under water. That night I was on baby duty, and I winced in pain when my 5-month-old grabbed my fingers. In the morning, I could hardly pick up a cup or type on a keyboard. My finger pads were sensitive to the touch. My hands hurt to clench. My right pinky finger had a subungual hematoma (bleeding under the nail). For days, I woke with burning fingers and needed to run my hands under cold water, apply lotion, and pop ibuprofen to ease the throbbing. And I was happy.

“Bravo!” Nichols emailed. “What a feat! Very impressive! If you were not sore today, I would have written you off as an extraterrestrial.”

Stephen Kurczy is a Connecticut-based journalist. His book The Quiet Zone, about an Appalachian town where cell phones and Wi-Fi are banned, will be published in 2021 by Dey Street Books.

If you enjoyed this story, you might consider subscribing to our Appalachia Journal.