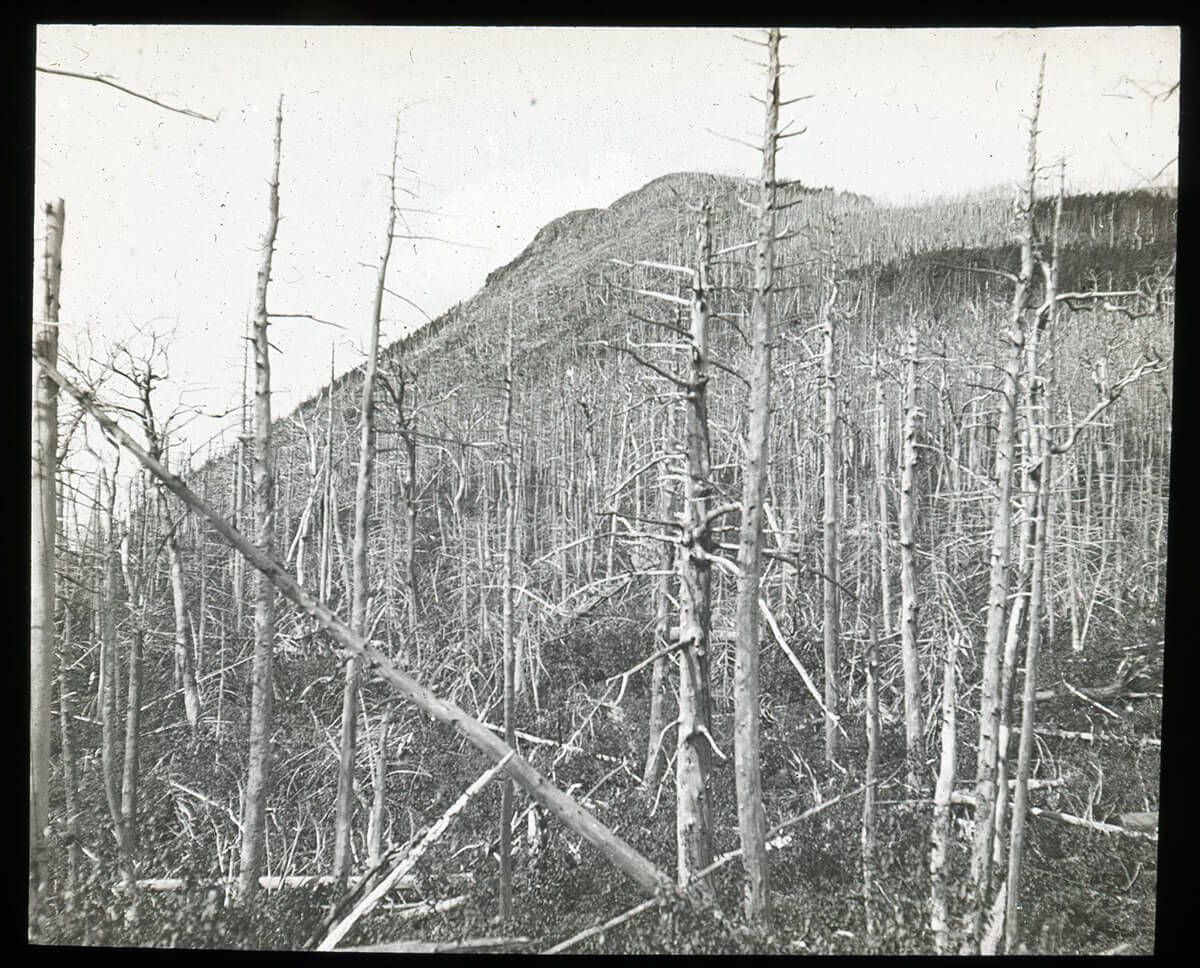

A view of a burned area between Mount Flume and Mount Liberty

It might be hard to believe that the now lush White Mountain National Forest was, just a century ago, barren and heavily logged. By the 1850s, about 70% of the land south of the White Mountains had been cleared of trees, due to the arrival of European settlers who used the area for agriculture and grazing. Logging interests extended north to the White Mountains with the creation of the Atlantic and St. Lawrence railroad, which made the northern forests more accessible. At the time, most of the land in the White Mountains was owned by the state, but in 1867, Governor Walter Harriman and the legislature sold the state’s White Mountain holdings to logging companies.

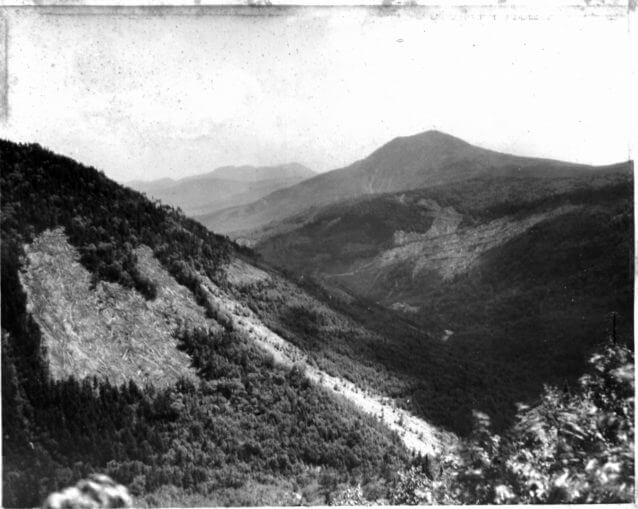

Without any sort of regulatory body, there were no restrictions on how much timber logging companies could strip from the mountains. This deforestation resulted in massive forest fires that caused ash to fall into nearby towns – blocking streams with silt and damaging watersheds that were vital to the industrial and agricultural towns located downstream. Members of these towns and regional tourists began to complain about the conditions of the forest and came to the consensus that something must be done.

A view of Carter Dome after a fire in 1903.

Despite significant Congressional action to set aside forest preserves in the West, not much was being done on a policy level in the East. In fact, Congress rejected over 40 bills calling for the establishment of eastern national forests for a variety of reasons: Some western congressmen were worried about losing funding to their eastern counterparts, and some representatives argued that funding should go to other causes. The House Speaker at the time, Joe Cannon, declared there would be “not one cent for scenery.” In addition, politicians noted that the federal government lacked the constitutional authority to purchase private land in a single state. Without proof of how purchasing the land would affect interstate commerce, the federal government had no jurisdiction to set aside forest preserves in individual states.

The impact of logging on the Pemigewasset Wilderness in 1910.

The momentum to conserve areas of the White Mountains slowed until Congressmen John Wingate Weeks, a Representative elected in 1905 from Massachusetts, proposed a bill that would allow the federal government to purchase private lands in order to protect the headwaters of rivers and watersheds in the East. As a frequent visitor to the White Mountains, Weeks was concerned about the damage that logging had done to the region. At first, his proposed bill went nowhere. He unsuccessfully presented to Congress numerous times, but could not build enough momentum for the bill to pass because there was still the concern about constitutional authority. Eventually, many New England and eastern organizations, like the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, got involved. Working together, these organizations began building support for Weeks’ bill.

At the time, the Appalachian Mountain Club was under the leadership of Allen Chamberlain, who advocated heavily for the protection of eastern forests. As a prolific journalist, he frequently wrote for the Boston Herald, Boston Post, Boston Transcript, and Appalachia, boldly lobbying for the protection of wild lands. A sample headline from one of his articles reads: “What Government Ownership Will Stop–Scalping the White Mountains.” Additionally, as a board member of the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, Chamberlain was perfectly positioned to accumulate support across different constituencies for the Weeks Act. He helped motivate and organize AMC members and other outdoor enthusiasts to get involved.

AMC’s involvement and mass support would prove crucial for the success of the Weeks Act. In 1904, AMC members were urged to exert their influence on Congressmen in support of a measure that would create a national reserve in New Hampshire. In 1906, the organization staged an equipment and forestry exhibit at the Boston Sportman’s Show, in part to educate the public about protection of the White Mountains. In 1908, a delegation of citizens from Massachusetts (including Harvey N. Shepherd who testified on behalf of the AMC) appeared at a hearing before the Committee on Agriculture of the House of Representatives on the issue of creating a forest reserve in the East. And in 1911, AMC formed a committee on the preservation of Crawford Notch Forest.

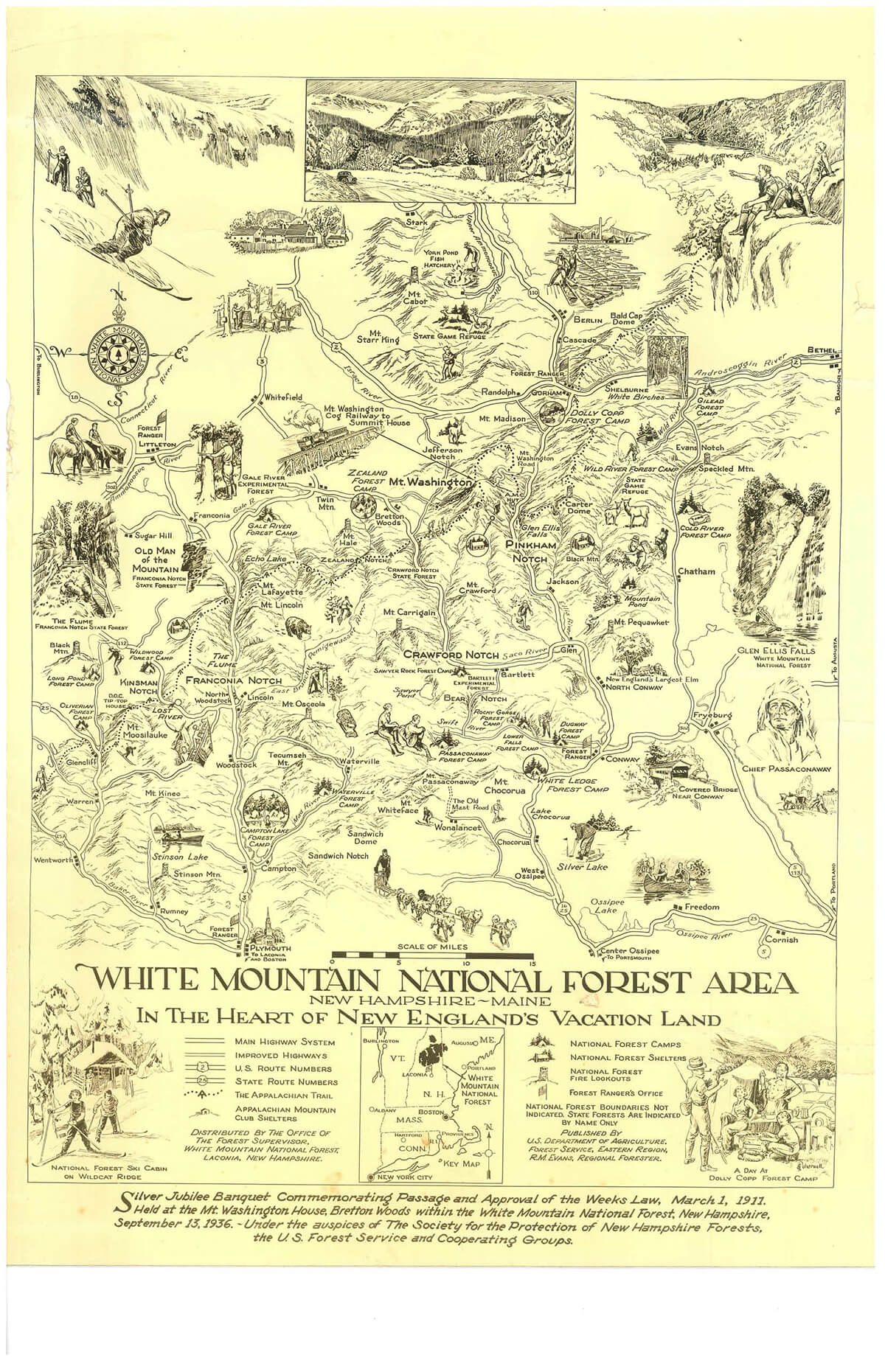

In addition to the support of AMC and other organizations, nature itself provided a strong argument for the necessity of forest cover in protecting watersheds. In March 1907, heavy rains brought flood waters racing through the East Coast, causing $100 million dollars in damage. As a result of this, the legislative branch was given the authority to create national forests. This allowed Weeks to amend his original bill. He added that the purchased lands would be permanently maintained as federal forest reserves, a move that would pass constitutional review under the commerce clause. Finally, after this amendment had been made, and after months of lobbying, delays, negotiations, and filibustering, Weeks’ bill eventually made it past both the House of Representatives and the Senate. On March 1, 1911, President William Howard Taft signed the Weeks Act into law. The AMC Council continued to get involved by appointing a committee in connection with the administration of the Weeks Act.

A map of the White Mountain National Forest following the passage of the Weeks Act.

The impact of the Weeks Act has been enormous, with conservationists calling it “one of the greatest pieces of federal legislation ever” and historians arguing that “no single law has been more important in the return of the forests to the eastern United States.” To date, nearly 20 million acres of forestland have been protected by the Weeks Act and over 40 National Forests have been established. In addition to the creation of the 780,000+ acre White Mountain National Forest in 1918, the Weeks Act also led to the creation of the Green Mountain National Forest, Pisgah National Forest, Allegheny National Forest, George Washington National Forest, and several others. Today, these forests prove extremely valuable for providing clean water, recreation, wildlife, forest products, economic opportunities, and several other services. Without the Weeks Act, it could be argued that there would be no White Mountain National Forest today.