This story was originally published in the Summer/Fall 2019 issue of Appalachia.

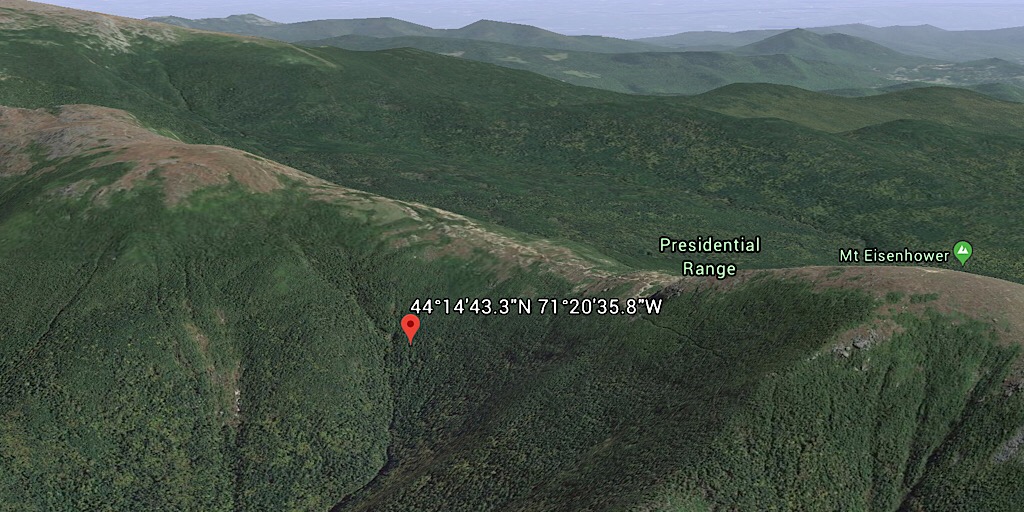

Dan McGinness is among the hiker elite in New England, where many of us admire his exploits. Four years ago, he endured a scary, unplanned overnight in mid-December. He agreed to show me where he’d hunkered down that night so that I could write this story. So we made our way to the ravine just north of Mount Eisenhower, where he’d spent that long night. We couldn’t drop down far enough, because we didn’t have the supporting snow underfoot. McGinness found a spot as low as he could reach to show the approximate arrangement. Nestled in the krummholz, it would have been a miserable experience, to be sure.

Four years ago, he endured a scary, unplanned overnight in mid-December. He agreed to show me where he’d hunkered down that night so that I could write this story.

We had made great time as we flew up the mountain, bounding strongly from rock to rock, gliding ever upward Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail. We both sweated and breathed hard as we progressed, but Dan had a lot more to give, whereas I had little speed left on the ascent. (In my defense, I had climbed another mountain that morning.) He could continue this for a mind-boggling number of hours. He has hiked not only the classic Presidential Traverse but has succeeded at this in both directions, back-to-back: from the Appalachia trailhead on Route 2 to the Highland Center, then back to Appalachia the way he came. That represents only a small sliver of what he has done since 2010, when he embraced the sport. Dan McGinness has performed some amazing feats beyond my ability and that of most people—even beyond that of most fit hikers.

This made me wonder: Can the strong win in the mountains? Can they prevail against all odds, coming out on top when pitted against nature?

This made me wonder: Can the strong win in the mountains? Can they prevail against all odds, coming out on top when pitted against nature? Well, sometimes they can, as I learned from Dan McGinness, but they need a bit of foresight, preparedness, and good old-fashioned fortitude. That’s what Dan had. He got himself into a bit of trouble in the White Mountains. But he saw himself through it. He had prepared fairly well, and he kept a clear head, but he is also quite simply a tough, resilient hiker. I’m not going to tell you a perfect story where our protagonist did everything right. That was not the case: Dan made mistakes that he has graciously shared with me so we can learn from them.

He learned the hard way, as we all do at one point or another. His compass, as you’ll learn, lay uselessly buried in his pack, for example. It should have been accessible, especially after his electronics quit on him; only a camera made it through the night. He also failed to take a sleeping pad, a sleeping bag, or many lower-body layers. All would have insulated him from the cold ground in an emergency. As a result, his night was far more uncomfortable than it needed to be. His lack of rest before the hike might have been too much for a lesser person. Dan also learned that once sweaty boots are exposed to freezing temperatures, getting them back on may be difficult, if not impossible.

What follows is an epic of self-rescue. A tale of involuntarily stranding overnight. A situation resulting not from injury but from an unrecoverable navigational challenge. The time and place is near-winter in the Presidential Range—which is like real winter everywhere else. It’s a tale of sound thinking, courage, and extreme fitness, together spelling the difference between life and death. After all, it doesn’t always end badly. Sometimes hikers save themselves.

What follows is an epic of self-rescue, a tale of involuntarily stranding overnight. A situation resulting not from injury but from an unrecoverable navigational challenge.

Let’s follow along on Dan McGinness’s adventure. Let’s learn from him.

Chapter 1: All According to Plan

Dan’s planned hike for the day was a “classic” Presidential Traverse, north to south from Mount Madison to Mount Pierce, with an atypical and difficult detour to Mount Isolation. He’d end up covering 26.5 miles with 11,700 feet of elevation gain when all was said and done. This route was extreme, yes, but Dan was “gridding,” meaning he was hiking all 48 of New Hampshire’s 4,000-footers in every month of the year, for a total of 576 summits. This sort of challenge was common for him. He could totally do this. He had a ton of practical experience, was super fit, and had completed similar—even tougher—hikes in the past.

The date was Sunday, December 14, 2014, when the forecast called for a good chance of awesomeness: a high temperature of 28 degrees Fahrenheit, winds maxing out in the 40s, with a lot of cloud cover and unsettled weather expected.

The date was Sunday, December 14, 2014, when the forecast called for a good chance of awesomeness: a high temperature of 28 degrees Fahrenheit, winds maxing out in the 40s, with a lot of cloud cover and unsettled weather expected. Visibility would be decent at ground level, and weather reports predicted a low chance of precipitation. All of this gave Dan’s plan a green light.

He started at the Appalachia trailhead on Route 2 in Randolph, New Hampshire. He met up with two friends and elite hikers, Jason and Andrew. They would accompany Dan for the first half of the traverse, bailing after Mount Washington. After a quick gear check, the trio set off at 8:35 a.m. up Valley Way, heading toward the col between mounts Madison and Adams.

Everything went according to plan. Stripped down to T-shirts and feeling great, they bagged Madison first, backtracked to the col, then hiked over to Adams to claim that mountain. The skies were littered with clouds, making for some interesting scenics. They experienced a momentary “fogbow” on Adams as they become enshrouded by a cloud. It was surreal, and McGinness and his companions loved it. The wind kicked up on this peak, but they hooted and hollered their pleasure.

They experienced a momentary “fogbow” on Adams as they become enshrouded by a cloud. It was surreal, and McGinness and his companions loved it.

They had business to attend to, so they didn’t linger. The clouds obscured their way off Adams—the cairns on Adams are notoriously small—and they began heading south on Star Lake Trail instead of west on Lowe’s Path. They quickly realized their error, backtracked to the top, and got on track. This happens up there more than people realize. Soon, they were moving westward across Edmands Col between mounts Adams and Jefferson. The latter was to be their next mountain summit.

The weather was better on Jefferson. Although they stumbled a bit on Adams, they made up for it on Jefferson and were treated to an undercast with clear, blue skies above them, while the clouds remained below. By 2:30 in the afternoon, the trio was taking a lazy break in Sphinx Col between mounts Jefferson and Clay. The temperatures were so mild they were shirtless during this stop. This is uncommon in the Northern Presidentials in mid- December. McGinness and his friends loved it. They didn’t forget their journey’s demands, though, so they moved on quickly.

They reached the 6,288-foot summit of Mount Washington at about 4 p.m. The clouds shrouded the sun, creating an unearthly orange glow. The temperatures dropped to freezing again, and some rime ice formed on their gear, signs, rocks, and cairns. These conditions, while really cool looking, slowed navigation. They removed their T-shirts and pulled on warmer layers.

Chapter 2: Going It Alone

Dan entered an area where he would see very few people, if anyone. His friends headed west down Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail, and Dan was now on his own, hiking south toward the aptly named Isolation.

As planned, Jason and Andrew left Dan about 0.4 mile below the Washington summit. The friends continued down toward the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Lakes of the Clouds Hut, while Dan veered off on Davis Path to bag Mount Isolation, taking a significant detour from a typical Presidential traverse. Dan entered an area where he would see very few people, if anyone. His friends headed west down Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail, and Dan was now on his own, hiking south toward the aptly named Isolation.

Unsurprisingly the trail resembled the mountain name. It was unbroken as Dan dipped into the boreal zone. Mount Isolation’s summit barely crests 4,000 feet. His progress slowed. Conifers lined the snowed-in path, heavy with encrusted snow and bent over the route, blocking Dan’s way. He pushed through with his body. Dogged determination drove him forward. Bear in mind that Dan wasn’t in over his head, nor was he out of his element. He was accustomed to this sort of difficulty. He often hiked at night, aligning his time in the alpine zone with astronomical events or significant dates in his calendar.

Dan reached Isolation’s dark, cold summit an hour and a half later. He didn’t linger, instead turning around and going back the way he came. He found the going slightly easier on the broken trail. He arrived at Boott Spur, then made his way across the flats toward Mount Monroe via Camel Trail. He enjoyed a brief Geminids meteor shower during this crossing, as he had hoped for. The skies cleared overhead long enough to allow this. His snowy detour to Isolation had soaked him with snow and sweat. “The heavy labor of ducking and crawling made me sweat on the way back,” he remembered. His outer layer “had become like a solid encrusted jacket.” Still, Dan felt strong, warm enough, and dry where he needed to be. He continued on through the evening accompanied by billions of stars, feeling exquisite and confident that the tough stuff was behind him. The weather at the moment was in his favor. That would change.

He continued on through the evening accompanied by billions of stars, feeling exquisite and confident that the tough stuff was behind him. The weather at the moment was in his favor. That would change.

Chapter 3: A Turn of Events

Reaching out to his family at around 10 p.m. while trying to stand out of the ever-increasing wind near Monroe’s summit, Dan used the last of his cell phone’s battery power. He expected to be done with his traverse by 1 or 2 a.m., and he managed to get a message out to his family before his phone went dead. It was time to move along to Mounts Franklin and Eisenhower. The end was near—and that was a relief, because Dan had to work in the morning. This was nuts, for sure, but for Dan, the “gridder,” it was pretty normal.

Dan descended the south side of Monroe toward Little Monroe then hiked toward Franklin and whatever unnamed mound comes next. He dropped steeply down toward the junction with Crawford Path, Mount Eisenhower Trail, and points south. It was dark, the wind cranked noisily, and the clouds now settled in around him, hampering his ability to see. Dan moved through an ice fog. This was not a hospitable place. He tried to stay on trail, but he struggled. Even in daylight, the area between Franklin and Eisenhower and its odd junctions can confuse hikers. He looked for the cairns that marked the way but couldn’t find them. He took out his GPS unit, hoping to find his precise location. But like his phone, that unit was dead, and the screen remained blank. The wind raged. A shiver went down his spine. He never set eyes on the junction sign. Dan was lost.

He continued on the best he could, still descending where he shouldn’t have been and heading more northwest than southwest, as needed. His compass sat deep in his pack. Instead of things getting easier, his way became more difficult. The stunted krummholz gave way to taller trees and deep, unbroken snow. Dan knew he was off-trail and felt pretty sure he had descended more than he should have. He yearned for and sought the hard-packed trail but instead found himself barely floating among taller trees, wading through deep snow, and seeking firm footing, “like a Plinko chip barely hanging on.” The forest poised to swallow him up and hide him until spring.

He looked for the cairns that marked the way but couldn’t find them. He took out his GPS unit, hoping to find his precise location. But like his phone, that unit was dead, and the screen remained blank. The wind raged. A shiver went down his spine. He never set eyes on the junction sign. Dan was lost.

The route was exhausting him as he tried to continue, discouraged, deflated, blinded, and maybe even getting a bit nervous. He was not one to be easily defeated, and admitting he felt anxious was new to him. Dan recognized he was wasting his time and energy, struggling to reacquire the trail. He was blinded by his own headlamp reflecting in the dense mist. If he continued, he might get himself into serious trouble by getting too wet, too tired, or too cold—as if the situation wasn’t already serious enough. At this point, Dan still had one really important thing going for him: He was lucid, thinking clearly, and not hypothermic. After all, losing one’s ability to reason can be fatal. Also in his favor, Dan had most of the proper gear and knew how to use it. He wisely decided it was time to employ it—while he still could.

Dan made a nest in the trees, first digging a narrow trench of sorts that he could slip farther into, out of the brisk wind and penetrating ice fog.

Dan made a nest in the trees, first digging a narrow trench of sorts that he could slip farther into, out of the brisk wind and penetrating ice fog. He then pulled supporting spruce boughs down over the trench bed. On top of these, he drew a tarp creating a fairly cozy home in the snow. He then donned the extra upper-body layers he carried. Thankfully it wasn’t an extreme night. The temperature had barely fallen below the freezing mark. The conditions still made up a recipe for hypothermia, but tonight freezing to death would be unlikely.

Unfortunately Dan didn’t have a sleeping bag or a pad, so he propped himself up on a hard-shell jacket to get off the cold, snowy ground. This was fine for a bit, but it didn’t work for long, because the snow kept melting underneath him. Dan was wet and cold. He would never get comfortable, this much was true, but survival situations are generally more about staying alive. He spent the night sitting up cross-legged in his makeshift shelter, boots removed, alternately rubbing his feet and shifting his butt. Dan felt no fear, but he wasn’t a happy camper. He felt discouraged. He waited for daybreak. He knew his trial could be much worse.

Chapter 4: The Aftermath

Dan made it. Morning came. All of his toes and fingers were intact, but his spirit was bruised. He struggled to put his now frozen boots back on—one of the worst experiences of his ordeal. Eventually he managed, then gathered the belongings that had probably saved his life and stuffed them back into his pack. He stood up and hiked up toward the top of the ridge in the col. He found himself just north of Mount Eisenhower, roughly at the Eisenhower/ Crawford Path junction. The sun was out, and Dan was feeling OK—so good that he decided to continue his traverse, first taking on Eisenhower, then summiting Mount Pierce.

Dan made it. Morning came. All of his toes and fingers were intact, but his spirit was bruised. He struggled to put his now frozen boots back on—one of the worst experiences of his ordeal. Eventually he managed, then gathered the belongings that had probably saved his life and stuffed them back into his pack.

After summiting Pierce he made his way back to Crawford Path and descended the trail toward his car. He called his family as soon as he could charge his phone. They had been worried, but they also had faith in Dan, his perseverance, his ability, and his will to live. Dan is strong, and those who know him know this truth. What might be too much for some, Dan can do—given enough gear and the experience and know-how to put it to use.

Dan said he will always pack a sleeping pad and sleeping bag for cold-weather treks in the Presidential Range. “I was very fortunate that temperatures did not drop too far below freezing that night,” he said. “It is always important to know your own limits, and if you find yourself in a similar situation, stay calm and focused enough to assess whether you are able to comfortably stop where you are or keep moving to keep warm.”

Mike Cherim is a search-and-rescue volunteer and a mountain guide and wilderness instructor for Redline Guiding in North Conway, New Hampshire.

If you enjoyed this story, you might consider subscribing to our Appalachia Journal.