Despite making many meaningful contributions to outdoor recreation and environmental movements, women are often less celebrated than their historical male counterparts. These nine adventurers and conservationists are just a few examples of women who have paved the way for a more equitable and inclusive outdoors.

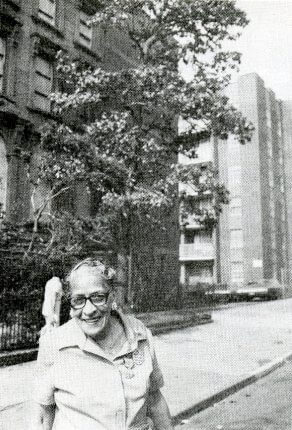

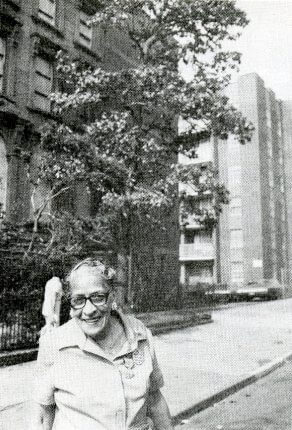

Arlene Blum

Arlene Blum / Arlene Blum Collection

Arlene Blum is a renowned alpinist and chemist. In 1978, Blum led the first American and all-women’s ascent of one of the world’s most dangerous peaks, Annapurna I in Nepal. She’s also led the first women’s team up Denali, completed the Great Himalayan Traverse, and hiked the length of the European Alps. Blum has a doctorate in biophysical chemistry from UC Berkeley. In the 1970s, her research helped persuade policy makers to remove toxic flame retardant chemicals from fabrics, such as those used for children’s pajamas. Blum founded the Green Science Policy Institute in 2008. As Executive Director, she continues her research to help prevent harmful chemicals from being used in consumer products.

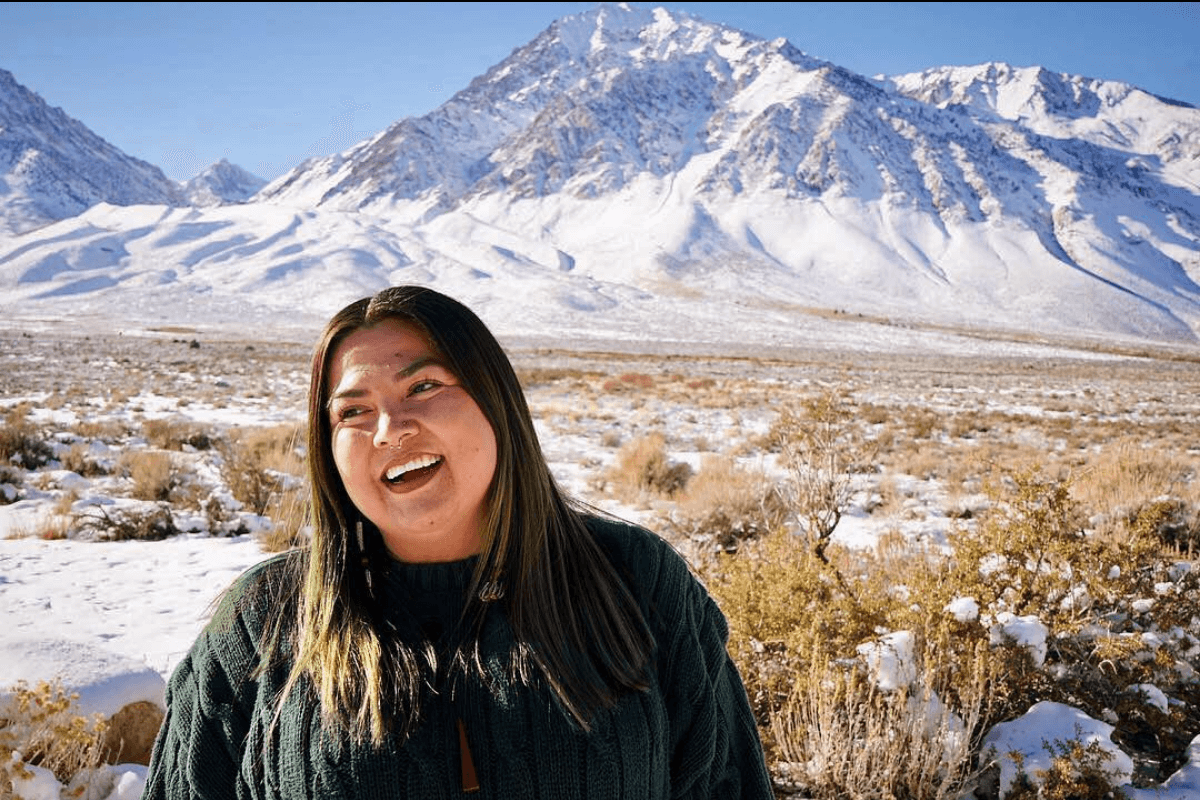

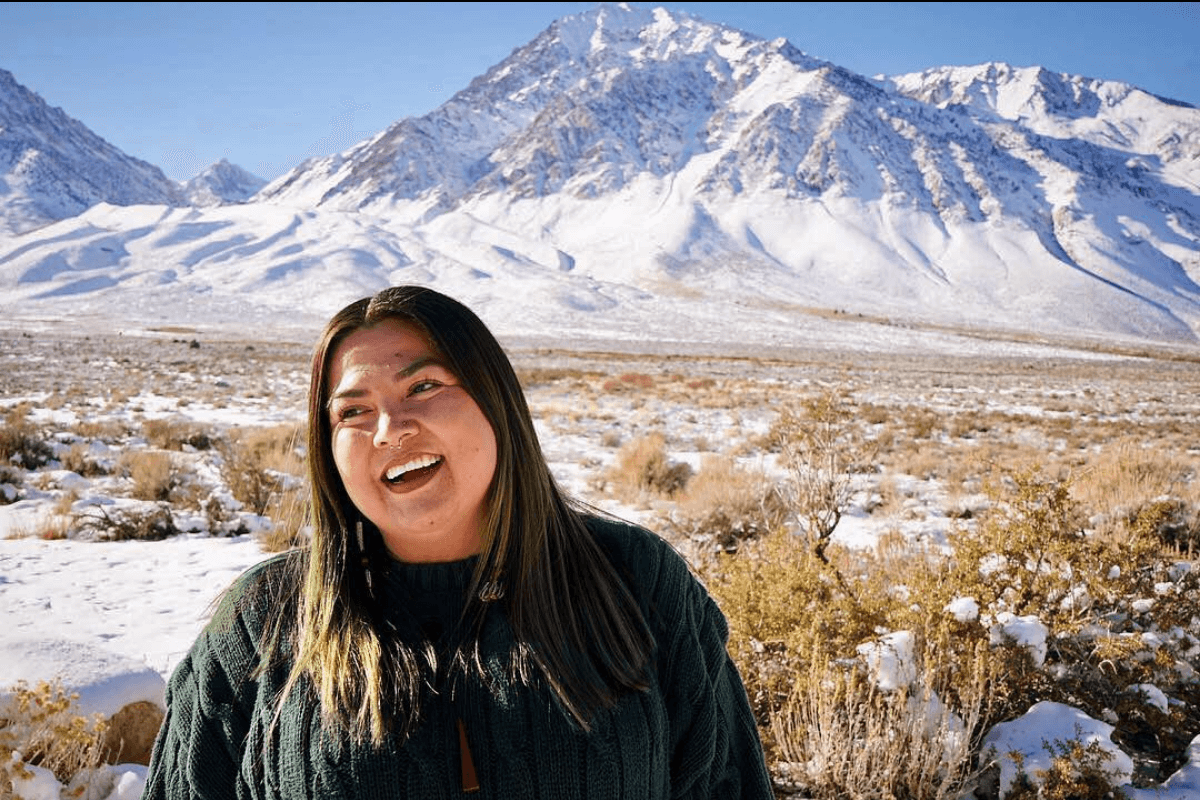

Jolie Varela

Jolie Varela / Photo by Autumn Harry @numu_wanderer

Jolie Varela is a hiking enthusiast and an environmental and social justice activist. She lives in Payahǖǖnadǖ – also known as the Owens Valley – and is a citizen of the Tule River Yokut and Paiute Nations. Varela first began hiking in her late 20s as a way to cope with depression and bipolar disorder. In 2017, she founded Indigenous Women Hike to help women in her community reconnect with the land and to promote both physical and mental health. In 2018, seven indigenous women, including Varela, hiked the Nüümü Poyo (directly translated as “the People’s Trail” – also known as the John Muir Trail). Through this trek, the group retraced their ancestor’s trading routes. Varela continues to lead hikes, has created a gear library to increase access to the outdoors for people in her local community, and is a tireless advocate for environmental protection and the decolonization of indigenous spaces.

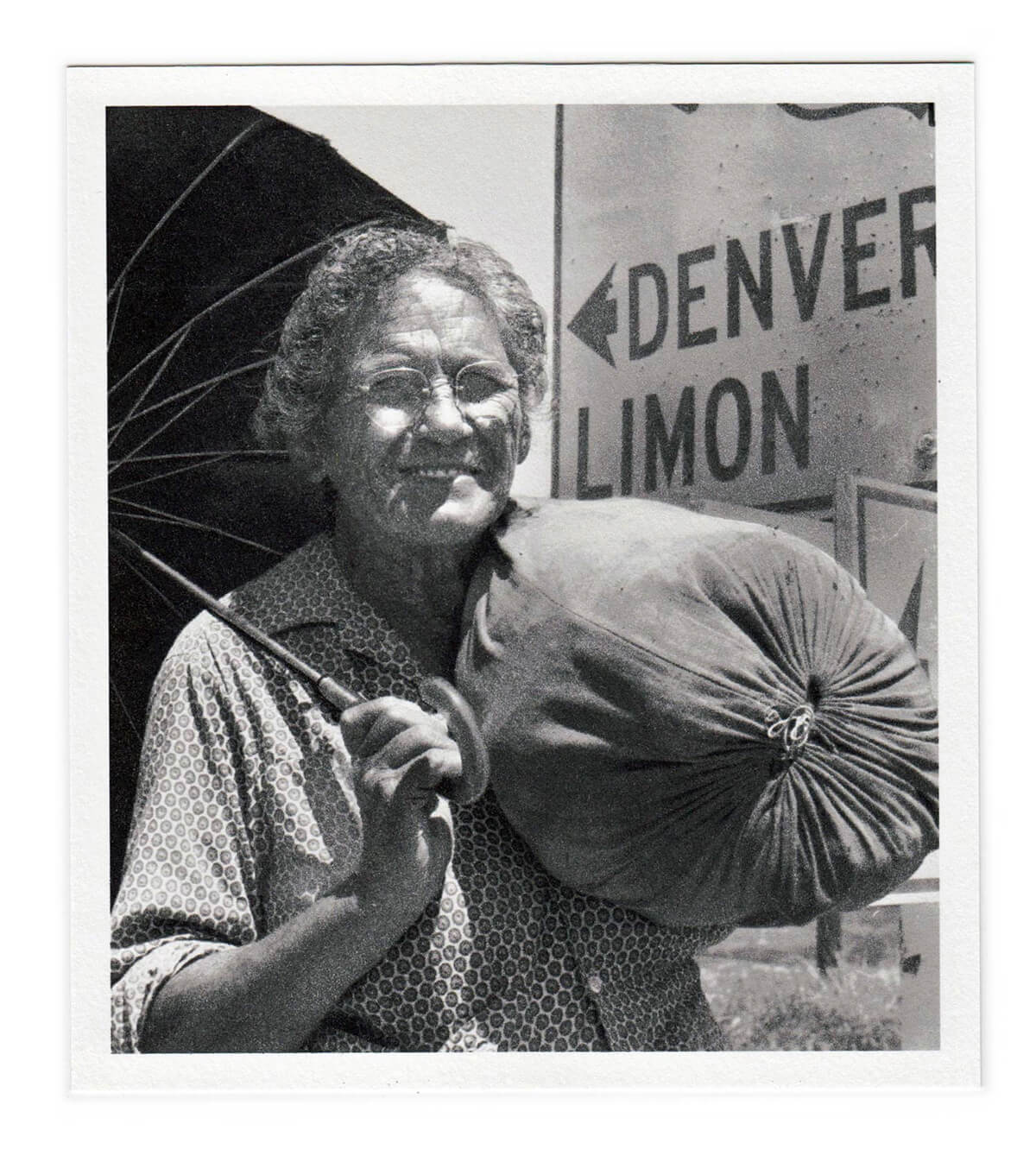

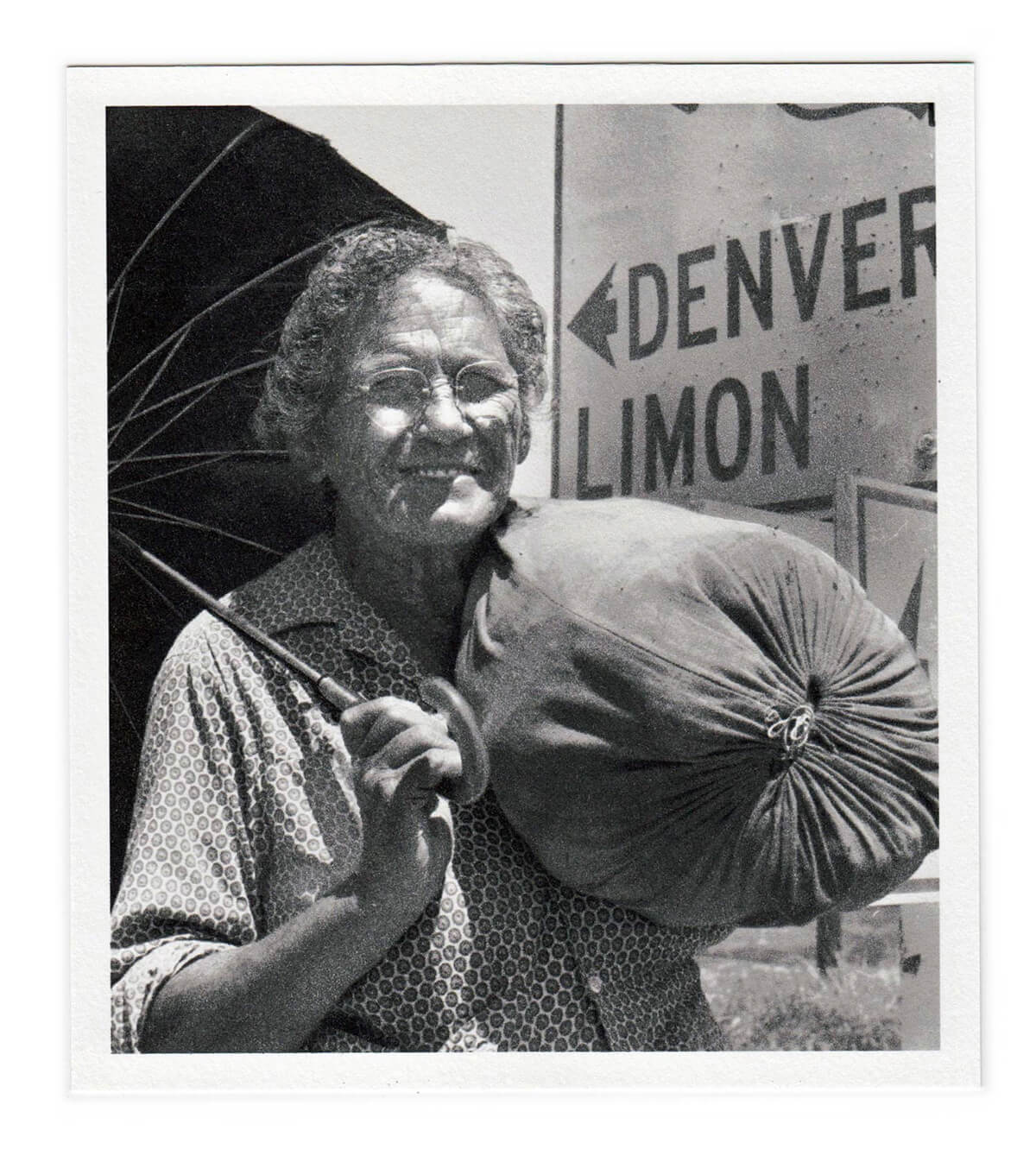

Emma Gatewood

Emma Gatewood

In 1955, Emma “Grandma” Gatewood became the first woman to hike the entire Appalachian Trail alone in one season. In her previous marriage, Gatewood had suffered 30 years of sexual and physical abuse from her husband and had often sought solace in the wilderness. After reading a National Geographic article about Earl Shaffer, the first man to thru-hike the AT, Gatewood reportedly said, “If those men can do it, I can do it.” At age 67, the great-grandmother traveled to Georgia from her home in Ohio to begin the 2,190-mile hike to Maine. Packing light, Grandma Gatewood carried only a few items – including a shower curtain to stay dry that she kept in a sack she had sewn. She reached Maine after 146 days, averaging 14 miles a day. Gatewood’s trek, which was widely published in newspapers at the time, continues to inspire people of all ages to try thru-hiking. By the time Gatewood died in 1973, she had hiked the length of the Appalachian Trail three times.

Hazel Johnson

Hazel Johnson meeting Al Gore at the White House / People for Community Recovery Archives, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature

Hazel Johnson is known as the “Mother of Environmental Justice” for her work on the South Side of Chicago. In 1969, her husband died of lung cancer at the age of 41. His death prompted Johnson to begin investigating and documenting the chronic health problems that were present in her local community. She discovered that a host of surrounding environmental hazards – including 50 landfills and multiple industrial facilities – were polluting the air, water, and land on the Southeast Side of Chicago. In the 1980s, Johnson’s organizing efforts caused city health officials to test the drinking water of South Side neighborhoods. After these tests revealed cyanide and toxins in the water, new water and sewer lines were installed in the area. Together with other environmental activists, Johnson’s advocacy led President Clinton to sign the Environmental Justice Executive Order in 1994. Johnson’s legacy has inspired hundreds of people to become involved in the environmental justice movement. Her organization, People for Community Recovery, continues to work to enhance the quality of life of residents living in communities affected by pollution.

Ynés Mexía

Ynés Mexía / The Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Ynés Mexía is considered to be one of the most influential and important botanists of the 20th century. In 1909, Mexía experienced a mental and physical breakdown that prompted her to move to San Francisco to seek medical care. While in recovery, she explored the mountains of Northern California and fell in love with the redwoods, plants, and animals of the region. In 1921, the 51-year-old enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley and found a new passion studying botany. Though she experienced some prejudice being an older Mexican woman at school, she went on to become one of the most prolific plant collectors of her time. During Mexia’s 13-year career, she traveled extensively in Mexico, South America, and Central America. During these trips (which were often carried out alone), Mexia collected nearly 150,000 specimens, described about 500 new species, and discovered two new genera. 50 plants are named in her honor and her collections are still used by researchers today.

Sophia Danenberg

Sophia Danenberg on the summit of Mount Everest, taken by her Sherpa, Pa Nuru

In 2006, Sophia Danenberg made history by becoming the first Black woman and the first African-American to reach the summit of Mount Everest. After discovering rock climbing in her early 20s, Danenberg’s passion grew to include ice climbing and mountaineering. Over the years, she has climbed some of the world’s most notable peaks – including Washington’s Mount Rainier, Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro, and Alaska’s Denali. Her climb of Mount Everest in the Himalayan mountain range lasted six weeks. Though she had assistance from her Sherpa, Pa Nuru, she did not travel with a traditional guide, and chose her own route and pace in addition to carrying most of her own gear. At 7 a.m. on May 19, 2006, Danenberg successfully summitted the highest peak in the world.

Hattie Carthan

Hattie Carthan / Hattie Carthan Collection, Brooklyn Public Library

Hattie Carthan was one of the first African-American community-based environmental activists in the US. During the 1960s, she began advocating to regreen her neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn after local trees began dying at an alarming rate. Over 1,500 ginkgo, sycamore, and honey locust trees were planted throughout Bed-Stuy as a result of Carthan’s leadership and community organizing efforts. In 1968, she began leading a campaign in Brooklyn to preserve an endangered tree, a magnolia grandiflora, that was being threatened by developers. Carthan helped secure a “living” landmark status for the tree in 1970. This success led her to be known as the “tree lady of Brooklyn.” In 1972, Carthan founded the Magnolia Tree Earth Center of Bedford-Stuyvesant, which continues to work on greening urban spaces, earth stewardship, and community sustainability.

Wangari Maathai

Wangari Maathai / Paris Global Forum

In 2004, Wangari Maathai became the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. During the announcement, the prize committee commended her “holistic approach to sustainable development that embraces democracy, human rights, and women’s rights in particular.” Twenty-seven years prior, Maathai had founded the Green Belt Movement in 1977 in an effort to slow the impacts of deforestation and desertification in Kenya and alleviate poverty. Over her lifetime, Maathai mobilized Kenyans to plant more than 30 million trees and provided income to over 900,000 women. In 1986, the Pan African Green Belt Network was established and other African countries began implementing their own tree planting initiatives. Maathai’s work also inspired the United Nations to launch the Billion Tree Campaign in 2006 which has since planted 11 billion trees worldwide.

Clare Marie Hodges

Claire Marie Hodges / National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center, Historic Photo Collection

Clare Marie Hodges became the first female National Park Service ranger in 1918. Born in Santa Cruz in 1890, Hodges fell in love with Yosemite National Park while visiting as a teenager. In 1916, she returned to the area and began working as a schoolteacher in Yosemite Valley. During World War I, there was a shortage of male applicants in the US workforce. As a result, many of the National Parks were understaffed. This deficit inspired Hodges to ask the superintendent of Yosemite National Park, Washington B. Lewis, for a job. According to National Park Service records, she said to him: “Probably you’ll laugh at me, but I want to be a ranger.” He responded, “I beat you to it, young lady. It’s been on my mind for some time to put a woman on one of these patrols.” This paved the way for a more inclusive and diverse National Park Service staff in the years to come.