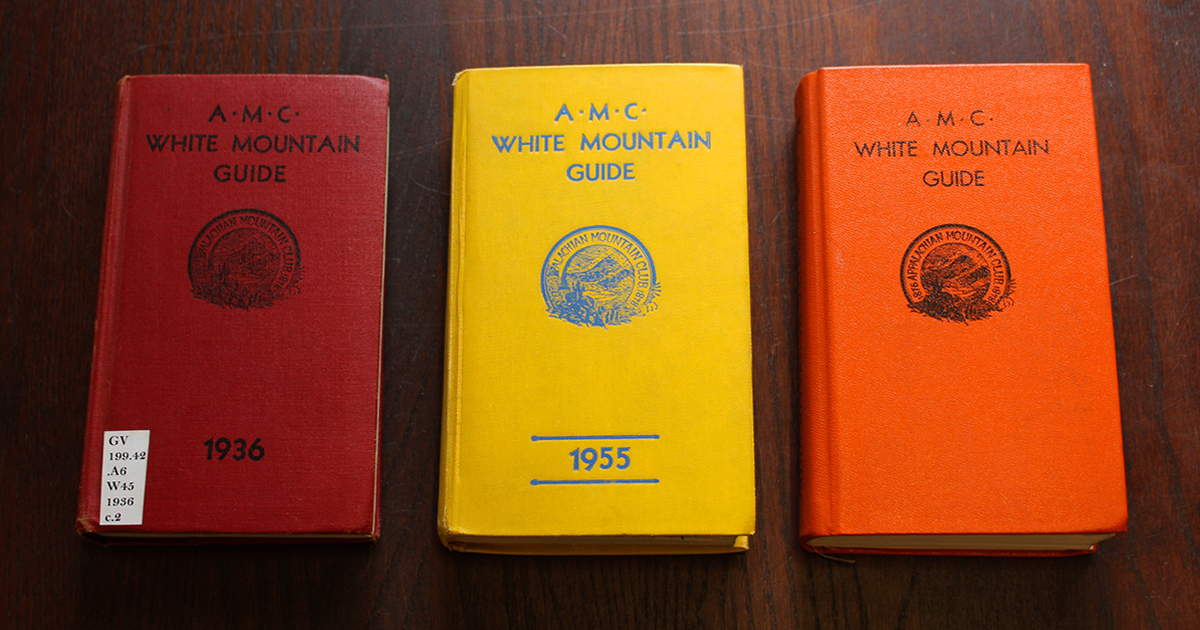

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

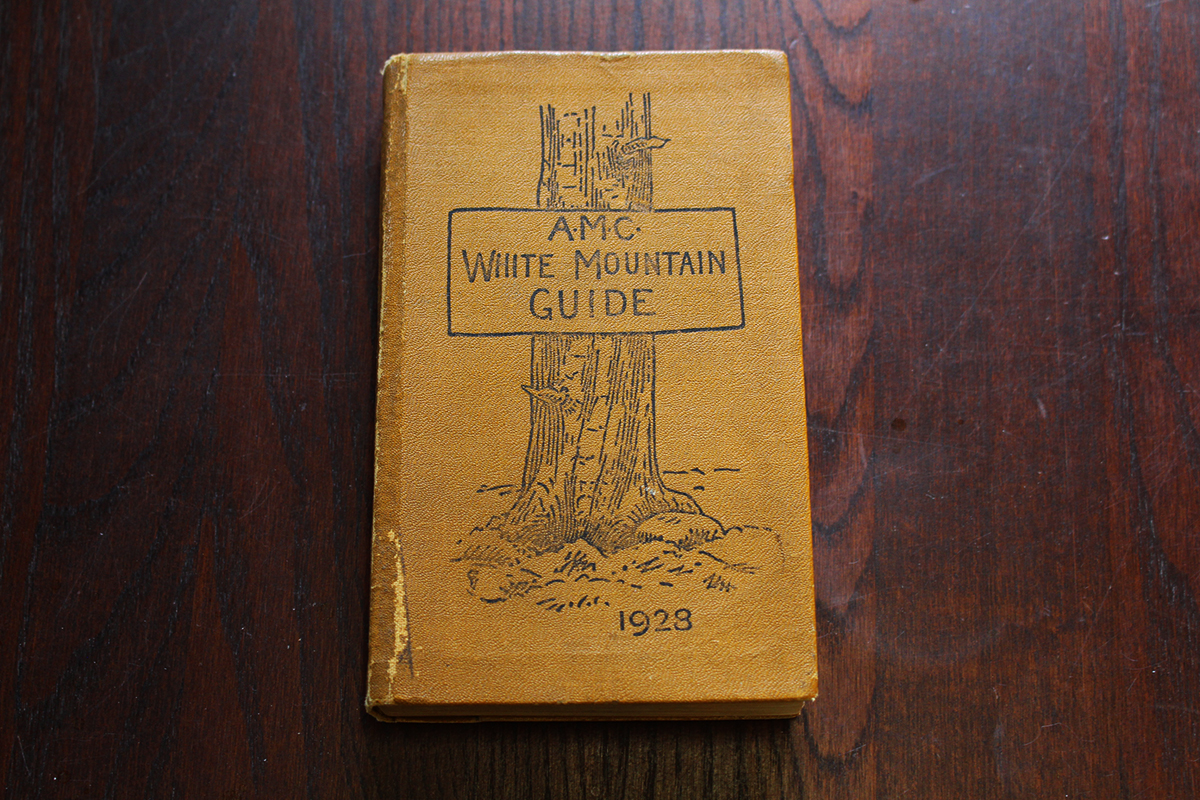

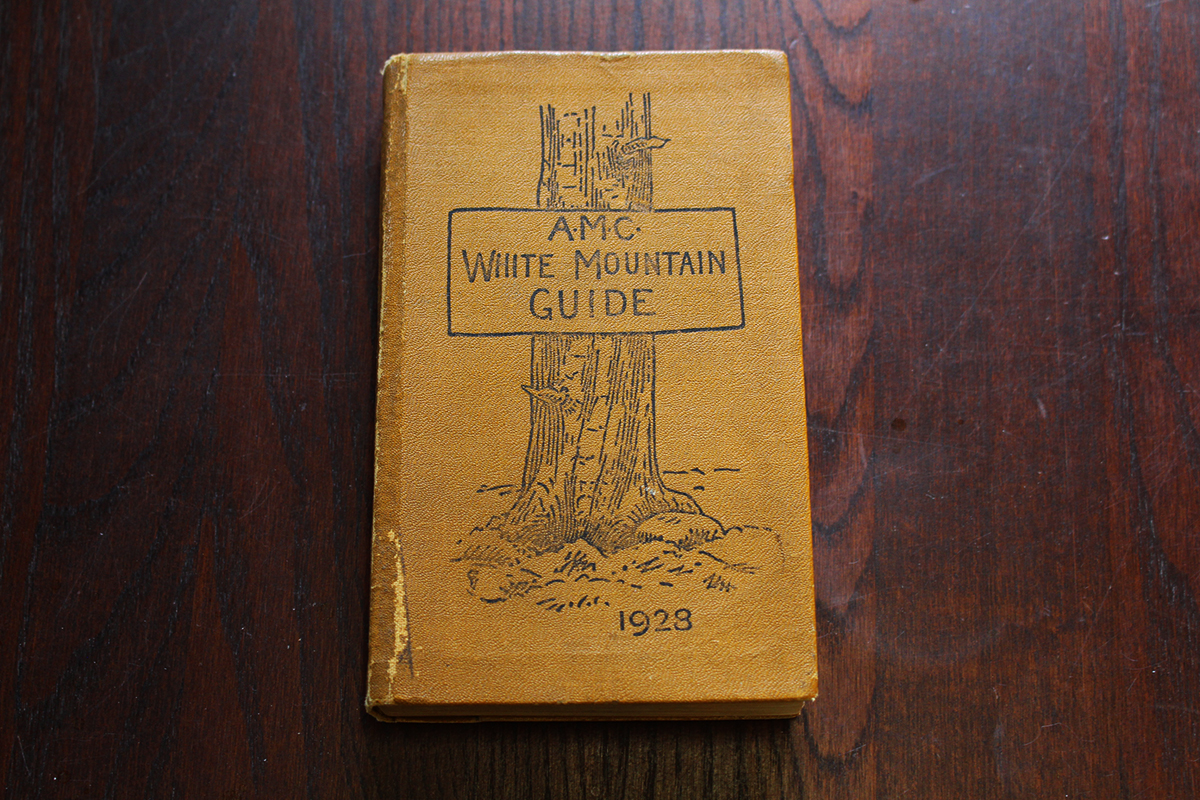

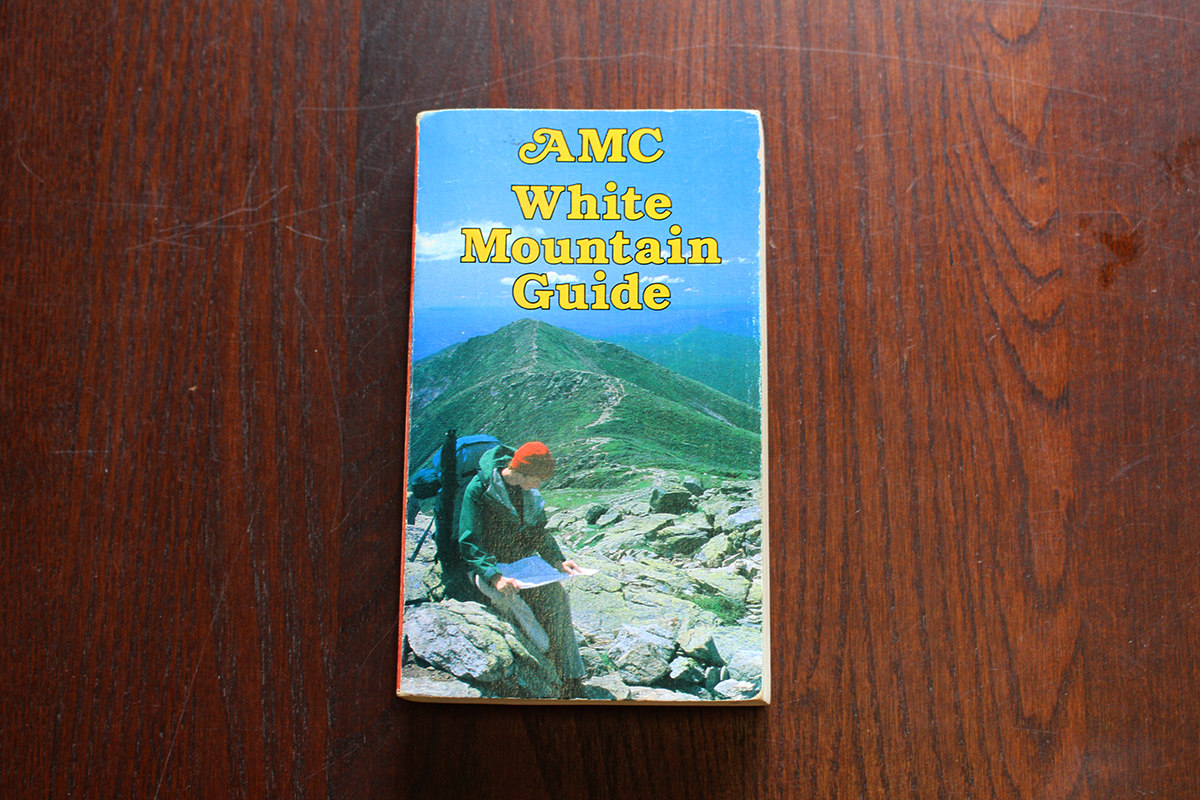

White Mountain Guide covers kept to a simple motif for a few decades.

“This is a pathfinder, pure and simple. Therefore, it is about as colorful as a railroad timetable.”

Ralph Larrabee, White Mountain Guide editor from 1917 to 1935, saw his publication in simple terms. But while the White Mountain Guide may be succinct, it has inspired more than a century of winding trails and colorful adventures.

The White Mountain Guide is the oldest, continuously published hiking guide in the United States; its first edition hit the shelves in 1907, and its 31st edition is now available. A lot has changed in that time: The White Mountains became a National Forest, the Appalachian Trail was created, and a few paths became a network of trails, shelters and huts. With each edition, the guidebook also changed with the times.

Through it all, however, the White Mountain Guide has remained “the Hiker’s Bible,” a definitive account of the footpaths of the region. Here’s to another 115 years of vibrant ecosystems, great trails, and outdoor adventure in the White Mountains!

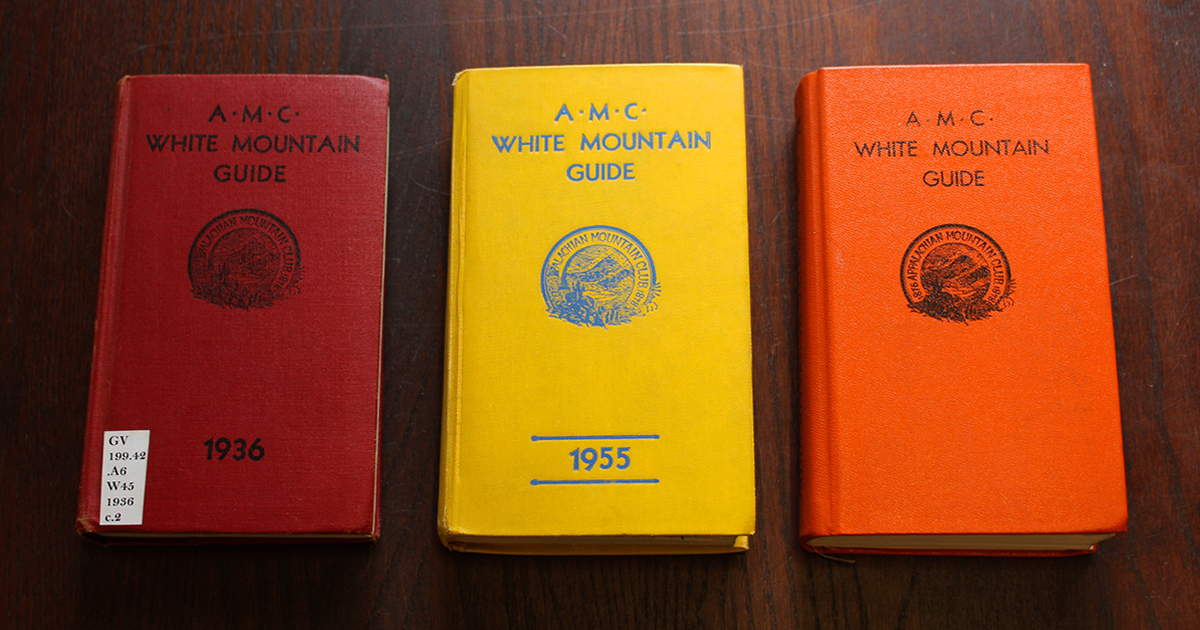

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

The one that started in all!

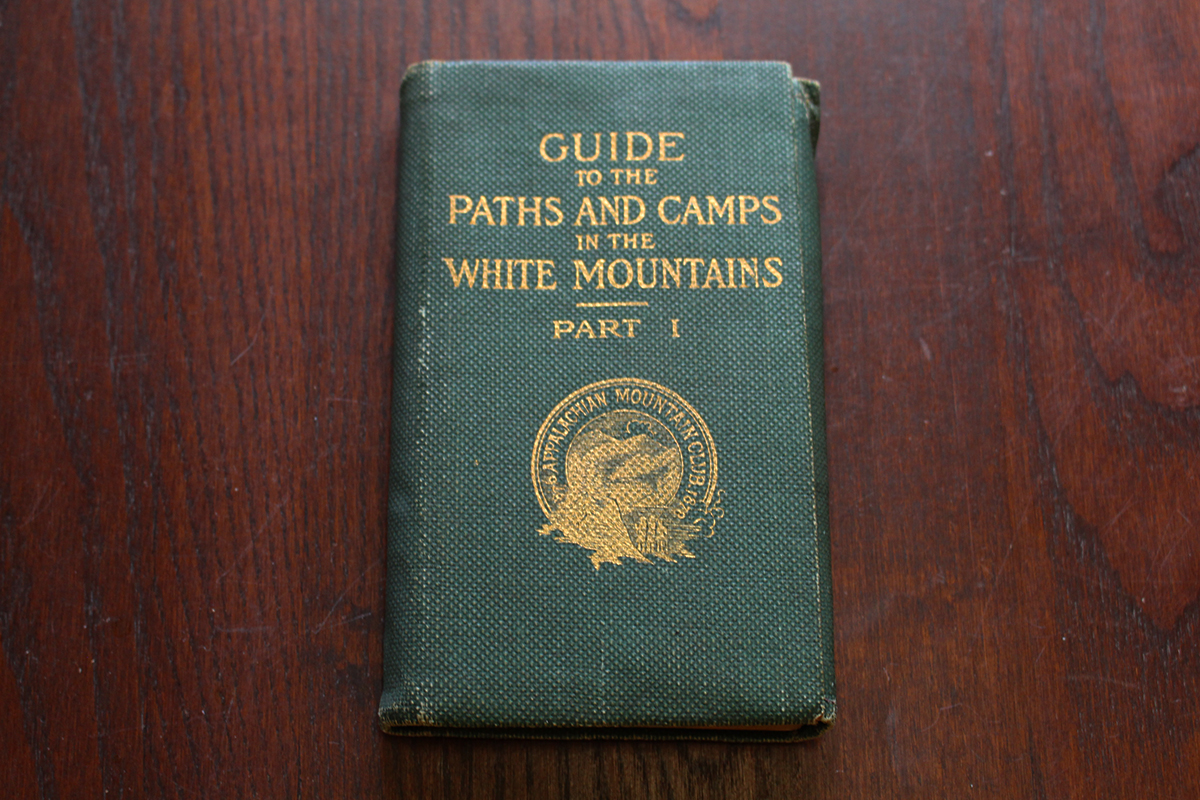

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

A 1915 cartoon of Louis Cutter and his cyclometer.

Origins

The first White Mountain Guide was a true team effort. While guidebooks had existed before the White Mountain Guide, most were geared toward tourists visiting the area’s luxury hotels and contained limited information on the region’s dense backcountry. To fill in the blanks, AMC leadership put out a call for information to its membership:

“A proposition, which it is hoped will prove of great value to the tramping [hiking] fraternity, is a Guide to the Paths and Camps, to be issued in the early summer, giving in condensed form descriptions and all available information as to [the] condition of the Club’s trails and camps. The hearty cooperation of Club members familiar with or having notes on this subject is earnestly required.”

Turning inward to the AMC’s membership made sense since the club was still in the process of building many of the trails referenced within the guide. In its earliest decades, key members of the guidebook committee included Harland Perkins, who helped design many of AMC’s White Mountain Huts and Paul Jenks, who was responsible for painting and placing thousands of trail signs. Other committee members from the early 20th century helped build the Kinsman Ridge and Wildcat Ridge trails, as well as reopen the Old Bridle Path and Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail.

The first edition of the book, Guide to Paths and Camps in the White Mountains, Part I, was released in July 1907. The text featured a comprehensive list of trails, divided into 11 geographic sections, and several maps. Impressively, the entire project was completed in just a year.

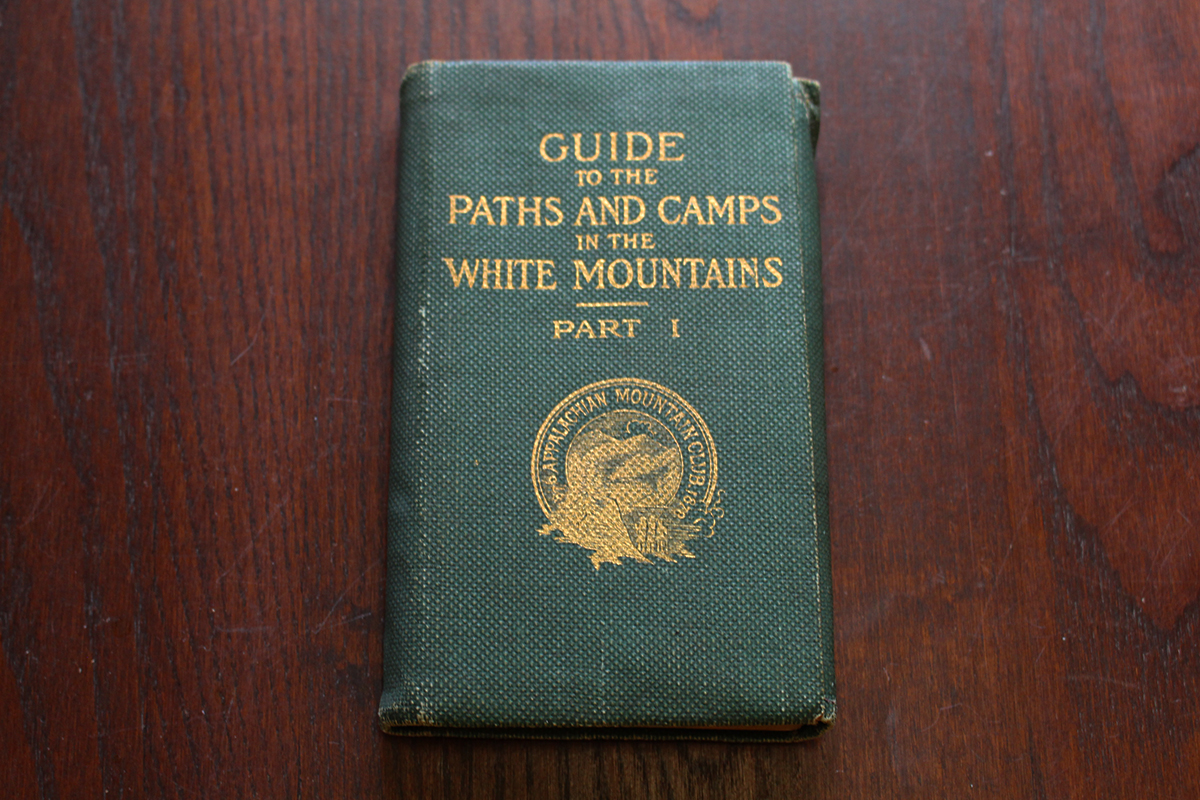

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

The “tree and sign” design lasted for several editions.

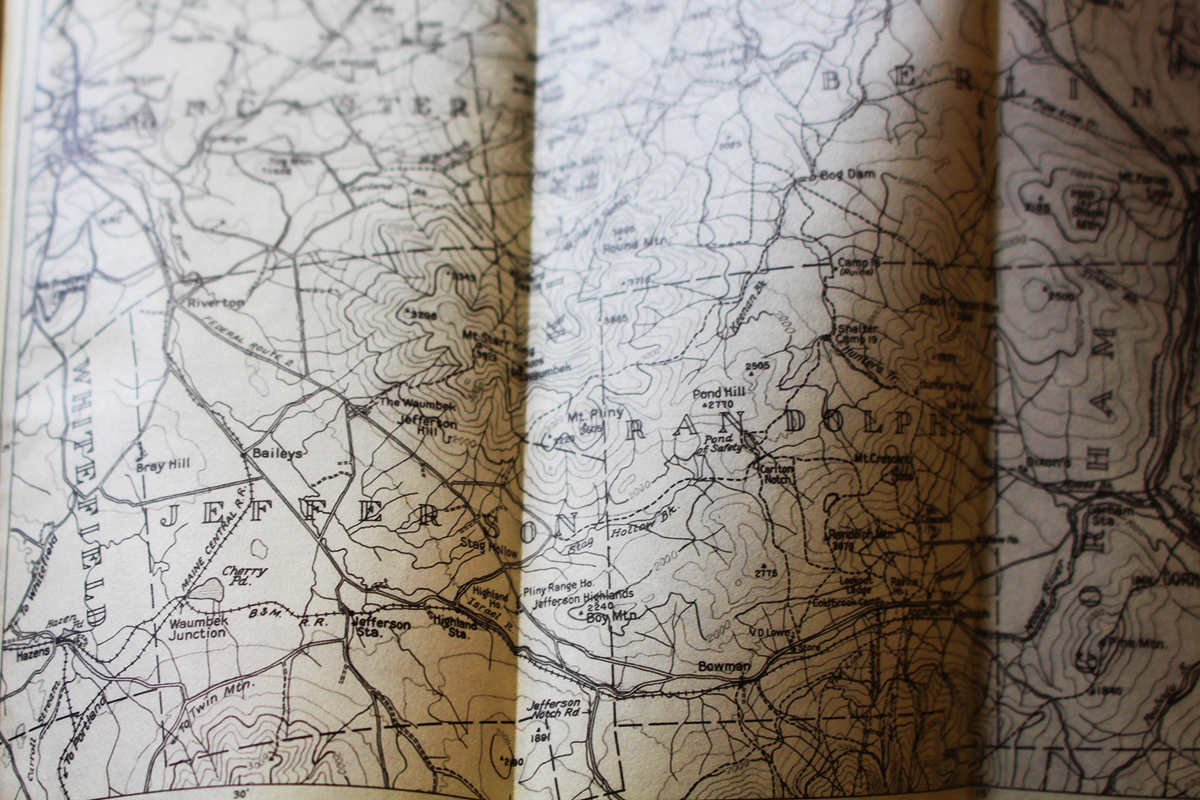

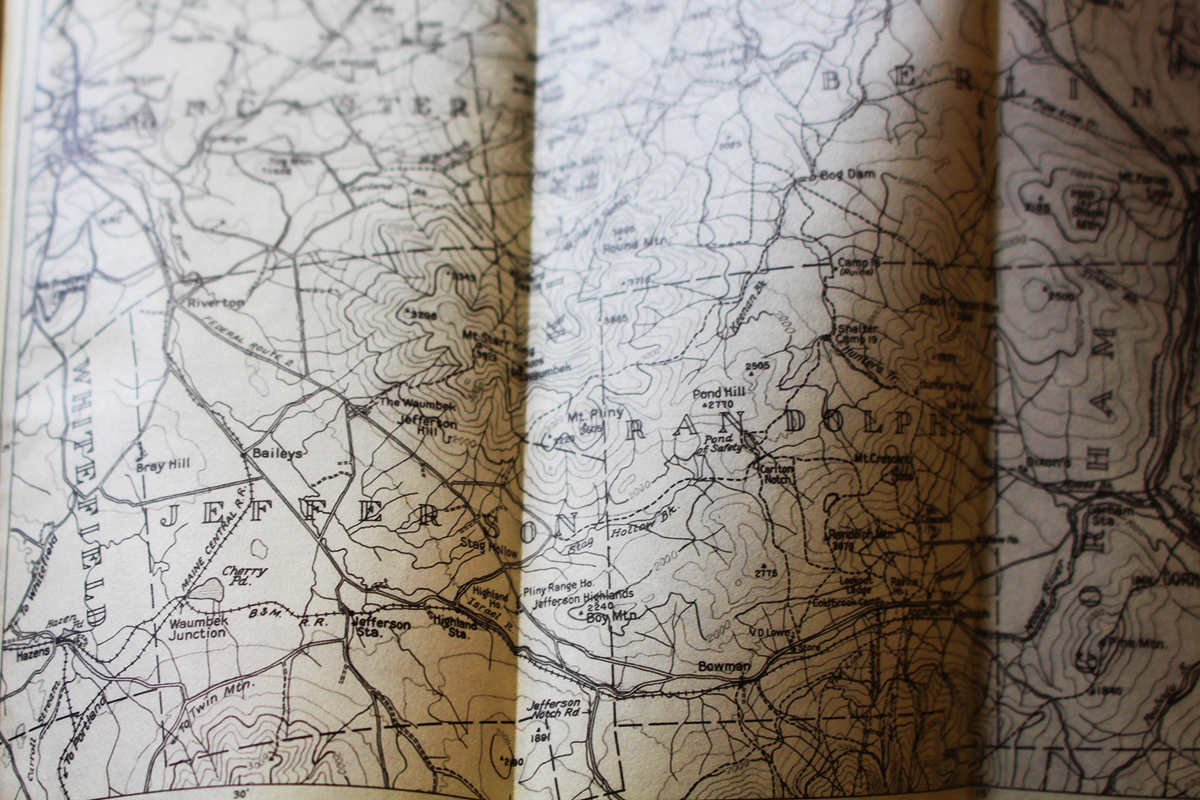

Mapping the White Mountains

The White Mountains of the early 20th century were a wilder place than they are today, and mapping them was a monumental task. In addition to tips from AMC members, the editors of early editions of the White Mountain Guide relied upon data from the U.S. Geological Survey and, often, simply hiking the trails themselves with whatever topographical equipment was available. For the first edition, AMC cartographer Louis Cutter fastened a cyclometer, a device that measures distance based on the rotation of a wheel, to the front half of a bicycle and walked it into the mountains.

As topography techniques have advanced, so have AMC’s methods. Today’s maps utilize Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) based topography for proven accuracy. That’s not to say that a human element isn’t still essential to the process.

“Having hiked most every trail we publish allows me to be ‘in the map’ when composing it and literally ‘draw upon’ and share my experience,” said Larry Garland, AMC’s current staff cartographer, in an interview with Avenza Maps.

Garland’s not exaggerating — in the 1990s, as GPS equipment was becoming readily available, Garland led an initiative to map the White Mountain National Forest by walking every trail with the device. While the technology may have improved, the spirit isn’t dissimilar to Cutter’s early hikes with half a bicycle and a cyclometer.

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

The first White Mountain Guide to feature a color photograph on the cover arrived in the 1980s.

More Than Hiking

Over time, the White Mountain Guide has expanded to include other forms of backcountry advice, and information for activities besides hiking. These have ranged from safety tips to a 1936 recipe for “Pinkham Notch Fly Dope,” a bug repellent concoction that included pine tar, olive oil, and a large tube of Vaseline.

Throughout its history the book has changed its emphasis, just as the club and the region have. Years with heavy snowfall included additional safety language, while editions created during periods of drought adjusted accordingly. During the backpacking boom of the 1970s, guides included more tips for beginners and even featured a “Carry In/Carry Out” logo at the end of each chapter to educate new outdoor enthusiasts on backcountry ethics.

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

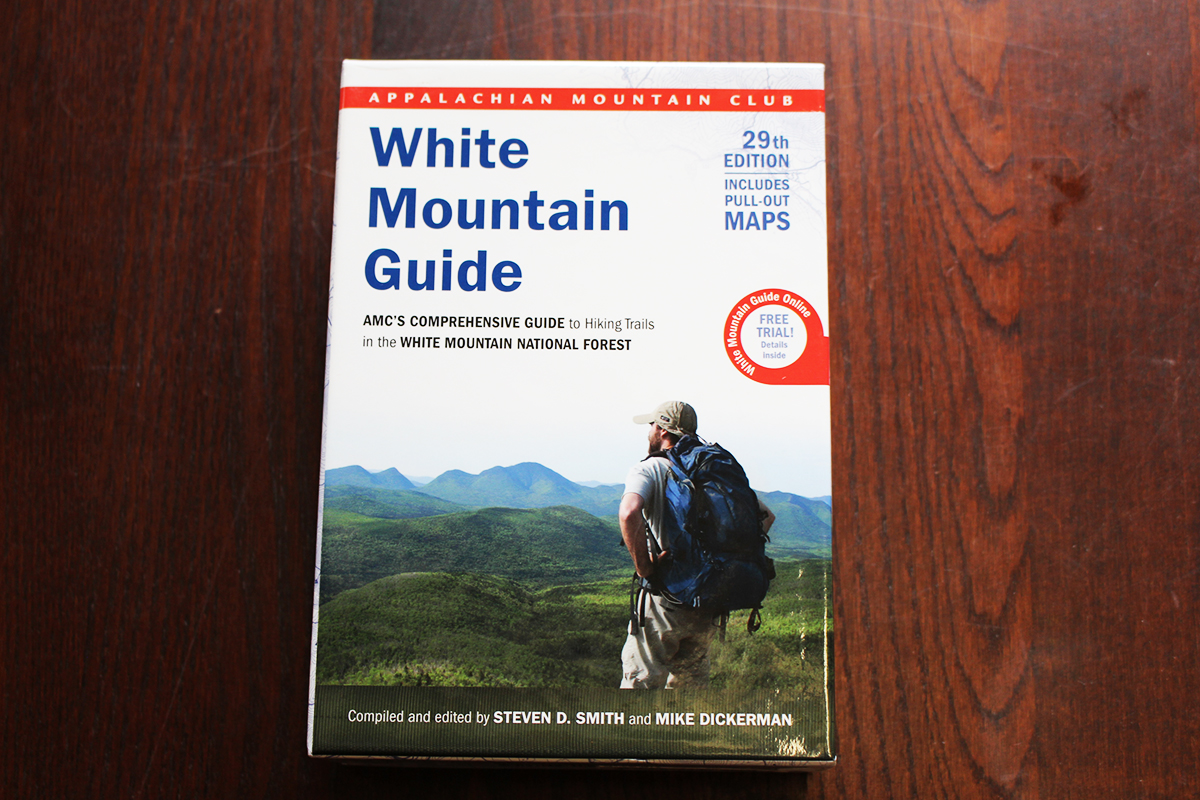

The 21st century White Mountain Guides would be unrecognizable to an early 20th century hiker.

The newest edition continues this tradition with suggested hikes for all ability levels, and at-a-glance icons for easy trip selection. The book also comes with six full-color, pull-out topographic maps, with trail segment mileage, and shuttle stops. Like each new edition of the White Mountain Guide, the book updates hikers to new reroutes and closures since the last publication.

All of this is designed to give readers the tools they need to explore and enjoy the outdoors, a fundamental part of the AMC mission. With each passing edition, the guidebook continues to inspire new generations to hit the trails. Take it from former editor and current author Steven Smith, who described the first White Mountain Guide he ever owned, the 1976 edition, like this,

“This compact little book… opened up a wondrous new world.”

Courtesy of AMC Library & Archives

A pullout map from an early White Mountain Guide.