Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory Library.

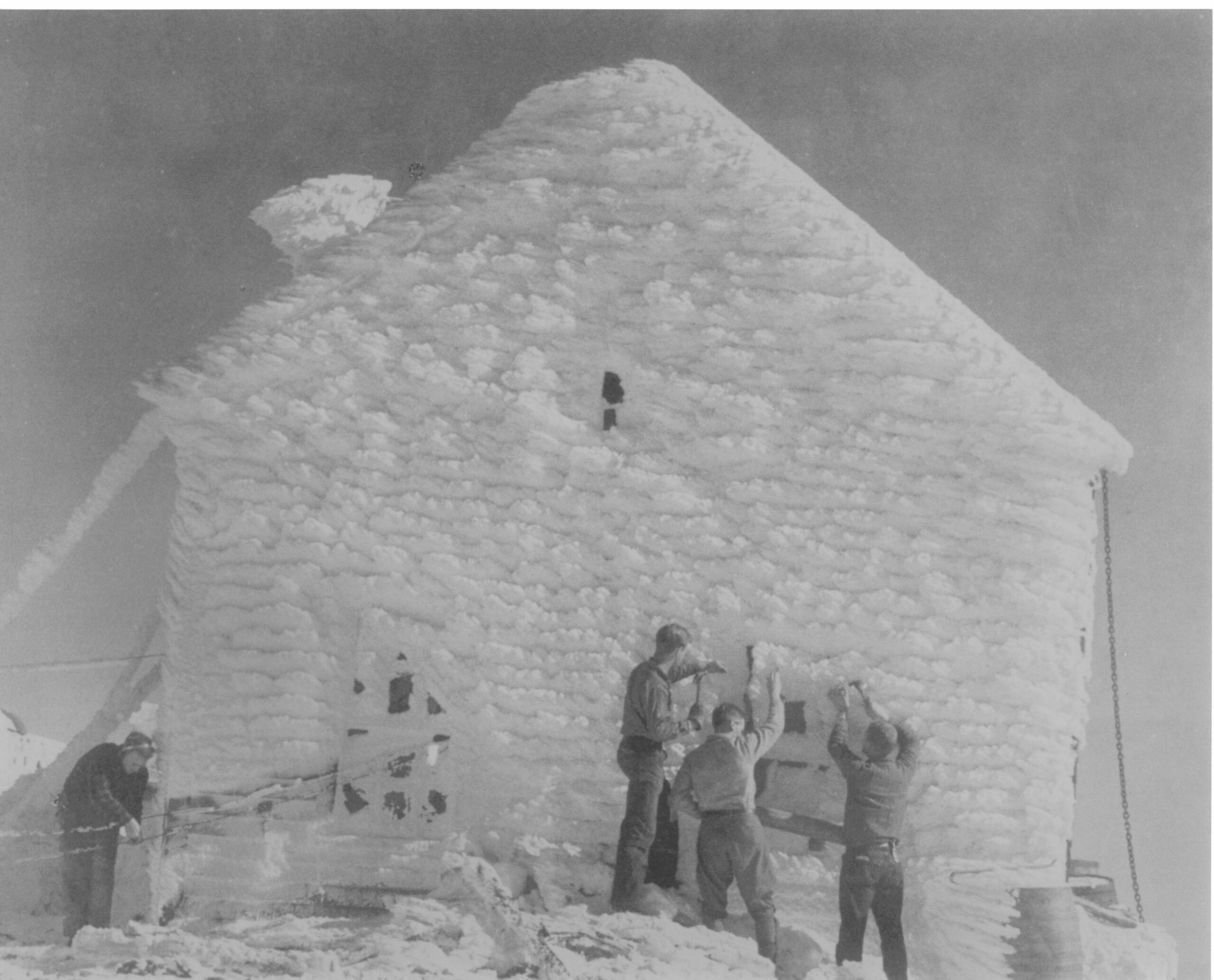

April 11, 1934: It was relatively warm on the summit of Mount Washington. Below freezing, but not by much. But more comfortable temperatures were not a reason for relief for the staff of the Mount Washington Observatory. Two walls of the observatory building were caked in ice nearly a foot deep and the wind was picking up. The observers decided to stay up in shifts that night, taking measurements with a radio to an anemometer (a special device for measuring wind speed) and a stopwatch.

“There was big weather out there, and the instruments would need tending,” wrote William Lowell Putnam in his history of the Observatory, The Worst Weather on Earth.

The wind picked up all night. By mid-day on April 12, Observatory staff were recording gusts of more than 200 miles–per hour. Then it happened.

231 miles–per hour. A world record for the highest wind speed ever recorded to date. Still the highest wind speed ever witnessed in person.

Capturing the measurement was a major scientific achievement for the fledging Mount Washington Observatory, then just eighteen months old. But it was also a victory for the Appalachian Mountain Club and its Huts Manager, Joe Dodge. Dodge was a life-long advocate for scientific research on New England’s highest peak and a co-founder of the observatory. All the men on the summit that day had been AMC employees at one time.

Today the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Mount Washington Observatory’s work and missions remain entwined. AMC’s backcountry huts in the White Mountains depend on forecasts from the observatory to prepare staff and guests for the day’s adventures. Scientists from the two organizations frequently collaborate to study the impacts of climate change on our region.

Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory Library.

The Beginnings

As long as people have been living near Mount Washington, they’ve been in awe of its wild, unpredictable weather.

The Abenaki name for the mountain is Agiocochook, which can be translated as “Mother Goddess of the Storm.” In the winter of 1870, Dartmouth College professor Charles H. Hitchcock and a small team built a temporary weather station in a railroad building, sharing reports via telegraph. The next year the U.S. Army Signal Service established a full-time weather station on the summit of Mount Washington. But when the government closed the project in 1892, the high peaks of the White Mountains were without consistent meteorological data for almost 40 years.

Until AMC Huts Manager Joe Dodge came along.

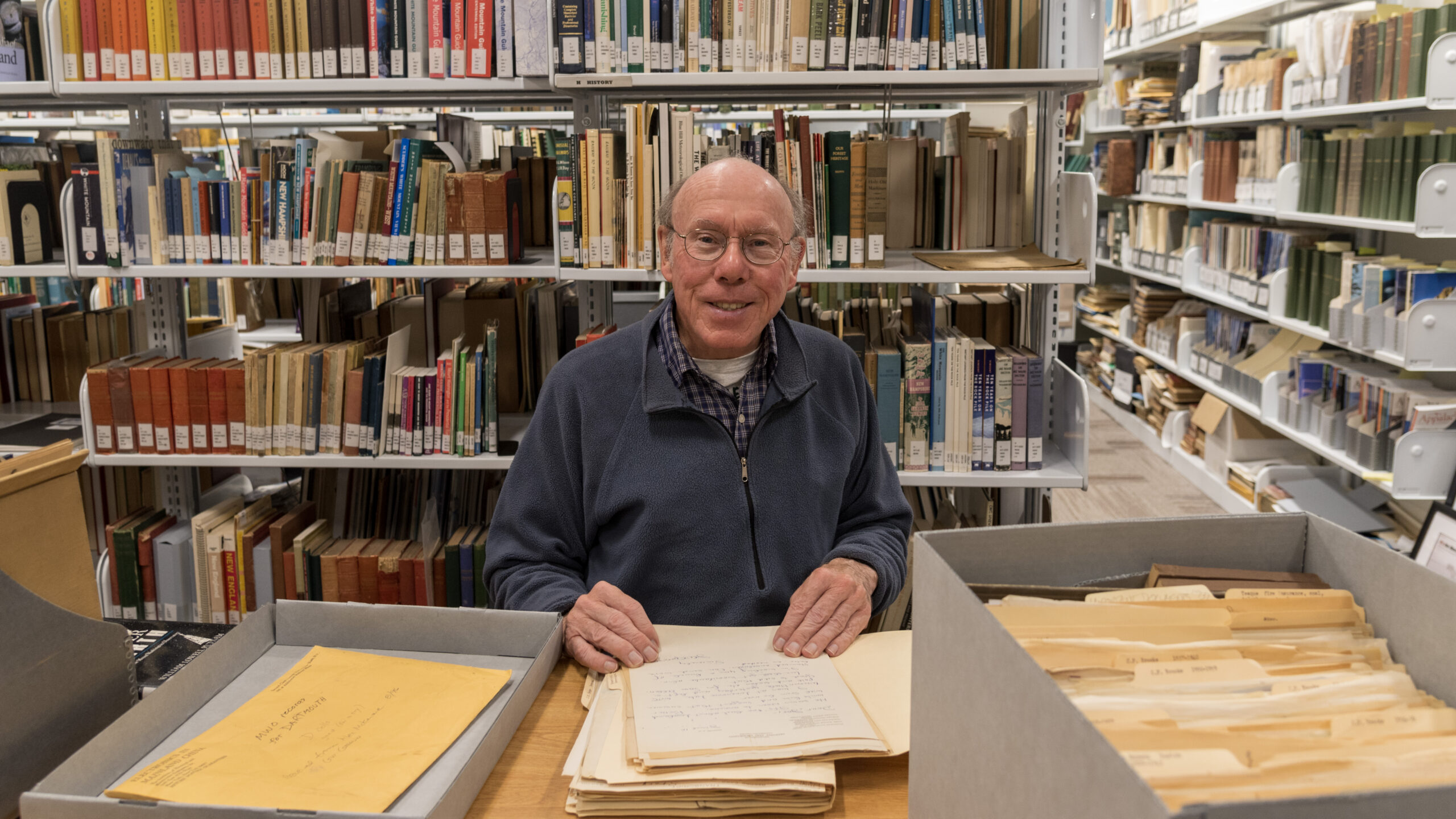

“Often, folks that have some knowledge of Joe think of him as just a long-time AMC huts manager. But he also had a very strong technical streak and scientific streak,” said Dr. Peter Crane, Mount Washington Observatory Curator.

Crane’s workplace, the Mount Washington Observatory’s Gladys Brooks Memorial Library in North Conway, New Hampshire, is filled with reminders of Dodge’s legacy: letters from Dodge to friends and donors, made out on both AMC and Observatory letterhead. Studious notes on the newest innovations in radio, a lifelong passion of his that would play a role in his co-founding a weather observatory.

Dr. Peter Crane in the Mount Washington Observatory Gladys Brooks Memorial Library, North Conway, New Hampshire. Photo by Matt Morris.

Joe Dodge was enamored with radio as a teen, even building his own amateur setup. When the U.S. entered World War I, he dropped out of high school and worked as a radio operator on a naval submarine. A few years after returning home, he moved to New Hampshire’s North Country and found work as the hutmaster at AMC Pinkham Notch Lodge. Today it’s called Joe Dodge Lodge.

Dodge soon saw the impact of the White Mountains’ volatile weather – and what it could mean to understand and predict it. In 1927, after historic flooding in New England, he worked with a Dartmouth College professor to set up precipitation recording at AMC’s backcountry huts. He then became a U.S. Weather Bureau official observer for the area.

Dodge made another Dartmouth connection around this time, future Observatory co-founder Bob Monahan. Monahan was just a college sophomore when he organized a Christmas break trip to take weather data on the summit of Mount Washington. He met Dodge passing through Pinkham Notch, and the two bonded over a shared desire to rebuild a year-round weather station on the mountain.

“[They] decided that that example given by the 19th century weather observers was too good to pass up. They talked about reinstalling or reoccupying Mount Washington,” said Crane.

Scientific funding during the Great Depression was hard to come by, but the pair found a way. In 1932 Dodge gave a presentation on the potential of an observatory at a meeting of the New Hampshire Academy of Science. His talk impressed Academy President James W. Goldthwait so much that the organization decided to make a major donation.

“[The Academy of Science] figured out how much they would need for their basic operations for another year. They set that money aside and everything else in the treasury was given to Joe Dodge for starting up the observatory,” said Crane.

Just like that, the Mount Washington Observatory was on its way to becoming a reality.

From left: McKenzie, Monahan, Dodge, Pagliuca. Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory Library.

The Early Observatory

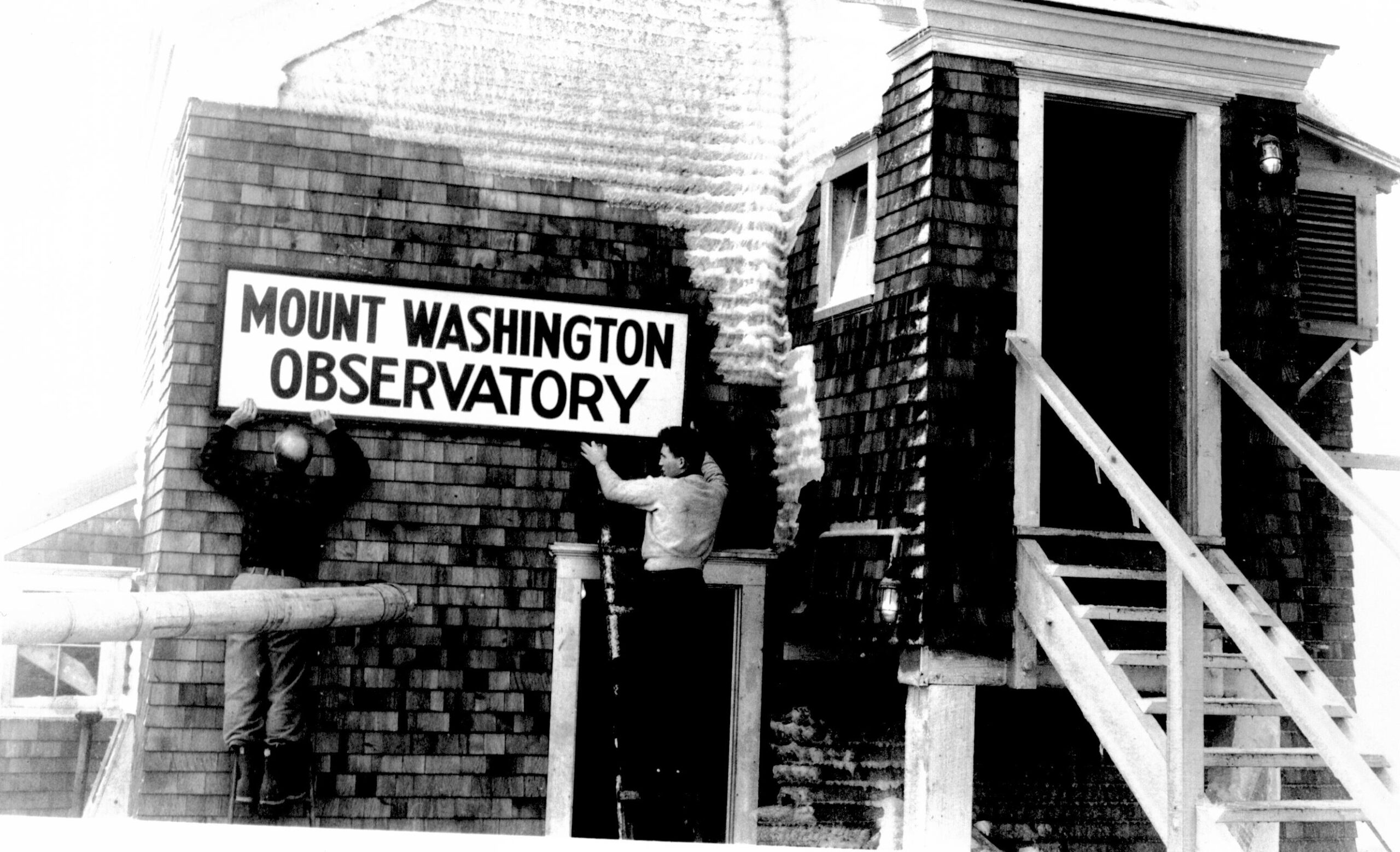

With funding secured, Dodge and Monahan set to work turning a seasonal office building on the summit (courtesy of the Mount Washington Summit Road Company) into a modern scientific station that could withstand inhospitable conditions. In written reflection on this time, Observatory mainstay Alex McKenzie remembered days of hard work, surrounded by friends from across the AMC hut system:

After the storm windows had been placed, the chains over the roof tightened, and all the work of making the place livable had been finished, we were free to start making our Observatory, installing instruments, wiring the house for electricity, building and setting up radio equipment. Joe had enlisted Itchy Mills… Ralph Batchelder, mule skinner and hutmaster par excellence, and Wen Stephenson, prospective hermit of Carter Notch, to help the Observatory crew at the start.

When construction was completed, a small crew hunkered down for the Mount Washington Observatory’s inaugural winter. Each had previously worked for the Appalachian Mountain Club. Monahan stayed on the summit full-time while Dodge split his duties between the Observatory and Pinkham Notch. Joining them was Galehead Hutmaster Salvatore Pagliuca and backcountry skiing pioneer Albert Fleetford Sise. McKenzie replaced Sise later that year.

Winter on the mountain was challenging. Trips halfway down the mountain for supplies could involve high winds and limited visibility. Most observatory staff only took five days off a month, and contact with the outside world was limited to the radio and occasional visitors.

“At the moment our last remaining friend had disappeared into the fog, we became men rather than boys,” recalled McKenzie.

But there were moments of joy. In Worst Weather on Earth, Putnam recounts a visit from Joe Dodge’s wife, Cherstine, carrying a batch of oatmeal cookies that “disappeared like magic.” The crew were kept company by a “monumentally unhousebroken” dog and a cat. While, supposedly, no one was excited to have the cat there, the tradition of the observatory cat continues to this day. By 1934 eight cats were living on the summit.

What attracted those early crews to the summit of Mount Washington? Conditions were tough and isolation near constant. Observers served on a volunteer basis, only receiving room and board. While the pay is much improved, the draw of working on New England’s highest peaks, whether as a meteorologist or AMC Hut Croo, remains the same for many: adventure and the comradery that comes with living in an environment unlike any other.

Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory Library.

Keeping the Backcountry Safe

With the tradition established by its founding staff and worldwide publicity after measuring a world record wind, the Mount Washington Observatory continued to grow. Staff moved from their borrowed office to a new facility and began a partnership with the U.S. Weather Bureau. They also integrated Joe Dodge’s first love, the radio, into their work. The results were pivotal not just for science, but for the outdoor recreation culture Dodge and the AMC were creating in the White Mountains.

“Reports about ski conditions and the weather forecasts were in part for safety reasons and part to encourage tourism… From a commercial angle for Joe [Dodge], he wanted to have a successful winter. He wanted skiers who came all the way up from Boston,” said Crane.

From the start Dodge and Alex McKenzie, a skilled radio technician in his own right, intended for the Observatory to share their weather reporting with the world. They began broadcasting their forecasts to the Blue Hill Observatory down in Milton, Massachusetts. From there, reports were shared with the U.S. Weather Bureau’s Boston Office and sent to a broadcast in Washington D.C., according to an article by McKenzie in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. The pair also found an important use for the radio closer to home.

In 1933 a young hiker named Simon Joseph went missing in cloudy conditions on his way to AMC Lakes of the Clouds Hut. To aid the search, Observatory staff sent the hut’s Croo a newfangled device they’d built over the winter – a twenty-pound portable radio system. While Joseph’s body was unfortunately found too late, the impact of using radio to coordinate a search did not go unnoticed. According to author Nicholas Howe in his book Not Without Peril, the effort had global implications for how rescues are carried out.

Alex McKenzie works the Observatory radio. Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory Library.

“The AMC was so impressed by reports of the Joseph episode that their high-elevation huts – Lakes, Madison, and Greenleaf – were equipped with portable two-way radios… Word spread, and by 1938 the Swiss were equipping their mountain refuges with thirty-pound portables.”

Perhaps more important than the searches the radio system aided are all the missions that never happened because radio communication between huts and the Observatory kept hikers informed about changing weather patterns.

Aside from improvements, it’s generally the same system both organizations use today.

Each morning at 7am sharp, hut Croos tune their radios to the Observatory’s daily forecast. Croos share these reports with their guests at breakfast and write them down for passing hikers to see. In a place where phones quickly lose battery and cell service is limited, radio reports give hikers the information they need to make smart decisions.

Understanding Climate Change

The Mount Washington Observatory doesn’t just collect its data for the daily weather forecast. Reports are stored for posterity, creating a reliable, consistent scientific record almost a century-long. Data sets like these are rare, especially in the backcountry. Between the Observatory and AMC’s 90 years of weather reporting at nearby Pinkham Notch, the Mount Washington area is fortunate to have two such records. By sharing their resources, scientists from the two organizations have taken advantage of a unique opportunity to understand the fragile environments they steward.

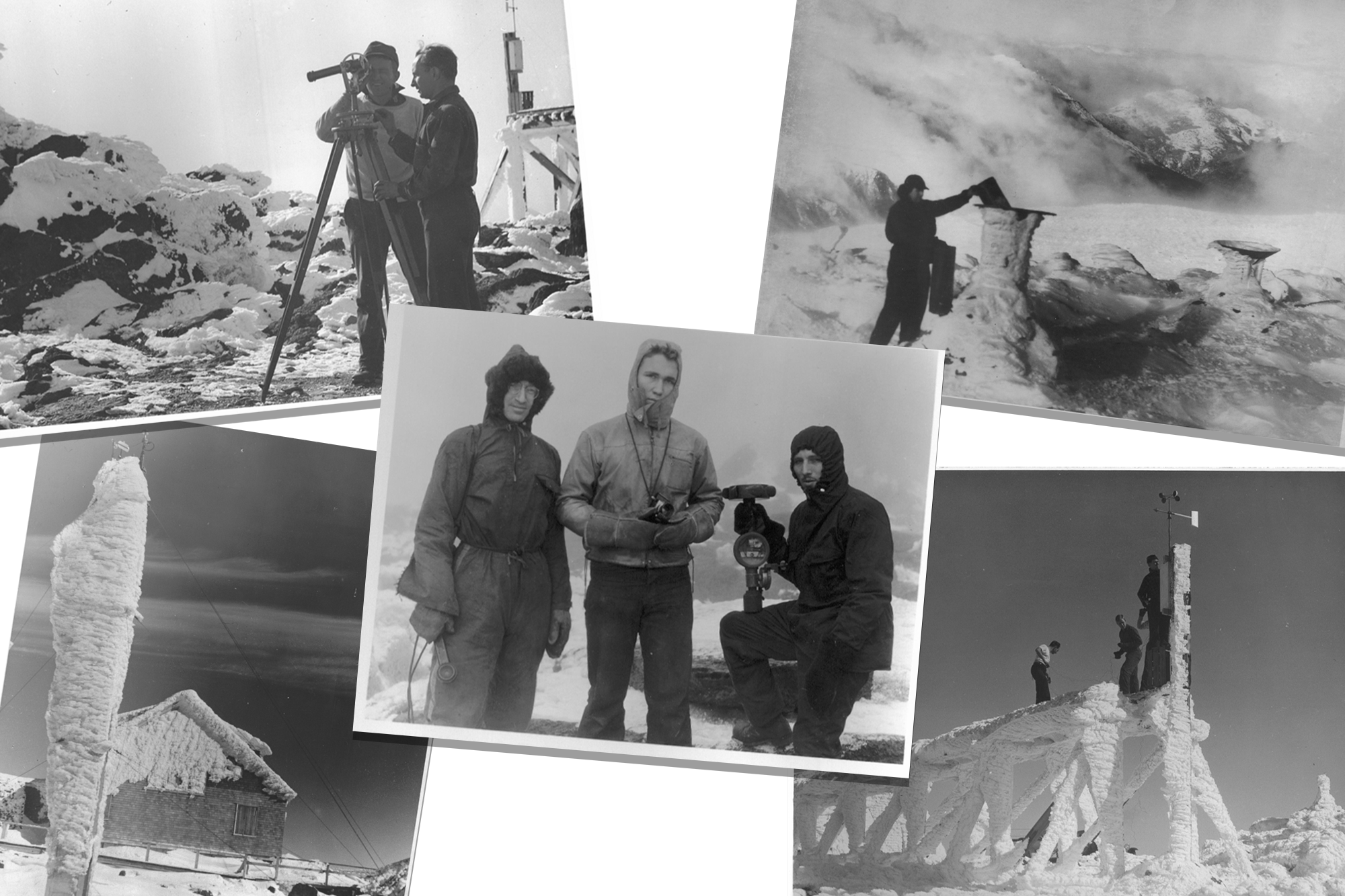

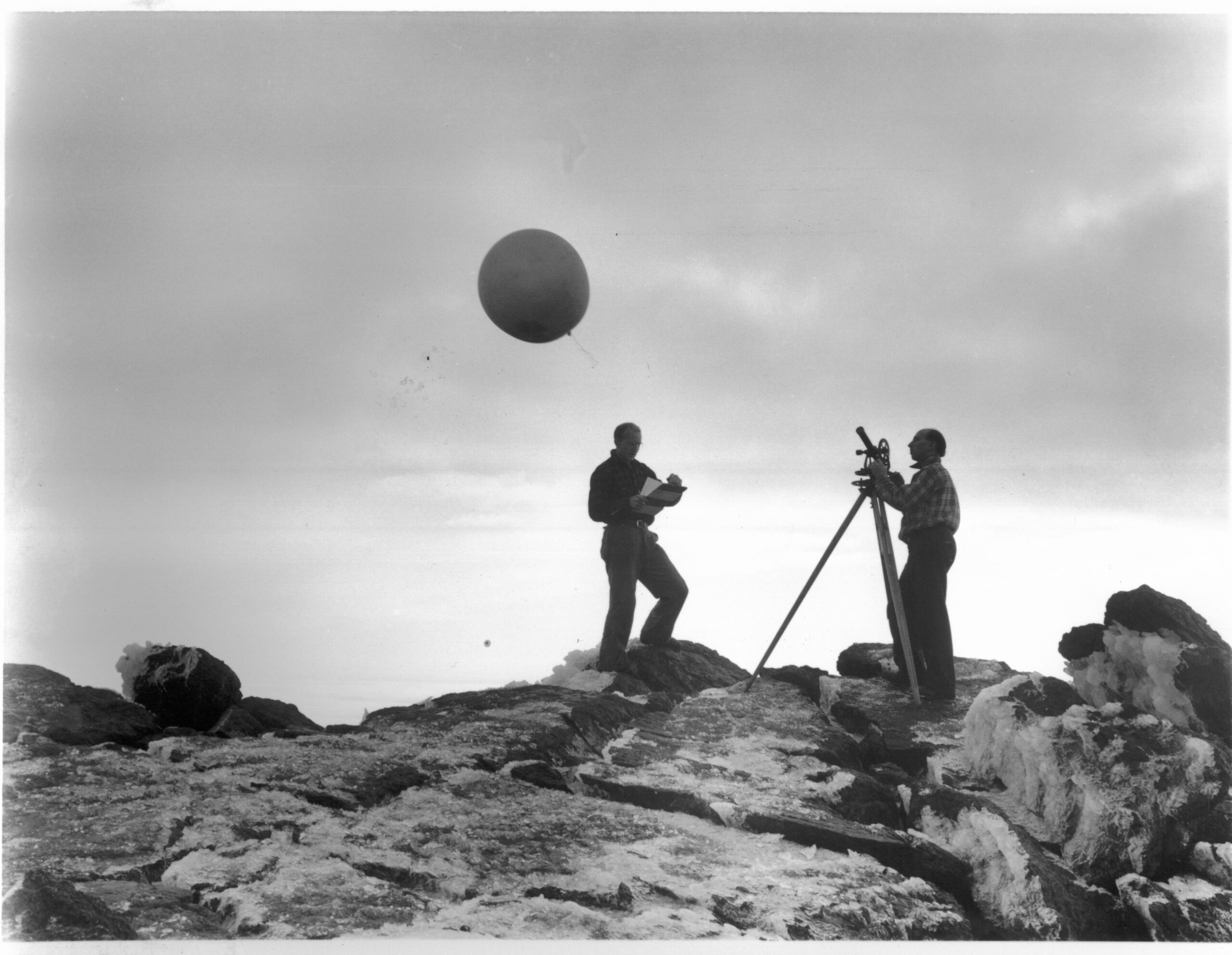

Observers using a weather balloon in the 1930s. Historic data helps today’s scientists understand climate change in the region. Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory Library.

In 2021 AMC Staff Scientist Georgia Murray published a study utilizing Observatory and Pinkham Notch data focused on temperatures and snowfall on Mount Washington from 1917 to the present. Murray found that New England’s highest peak, once relatively insulated from the impacts of climate change, is now warming at a statistically significant rate. Since 1917 the mountain has seen 20 fewer “frost days,” or days where the temperature is below freezing. Snowpack is declining, and the growing season for plants is getting longer.

Much of that change has been in the last 20 years.

“Our paper found that for the first time, the summit is tipping to what we call significantly warming,” said Murray, speaking to WMUR.

The founders of the Mount Washington Observatory may not have had climate change on their minds, but their measurements have proved instrumental to our understanding of its effects in the Northeast.

“Since 1932, Mount Washington Observatory has built one of only a few high-altitude, long-term records of weather and climate worldwide. This record provides huge benefits to scientific research, including our own climate studies, grant-funded projects, partnerships with universities, and product testing,” says Observatory Executive Director Drew Bush.

Research like Murray’s informs policymakers and the public about the real, immediate, and close-to-home impact of climate change. Without the longstanding scientific relationship between AMC and the Mount Washington Observatory, a big piece of the report would have been missing.

“Our missions are different, but the passion is the same… We couldn’t do this climate work without what they’re doing up there,” says Murray.

The Mount Washington Observatory in the 21st century. Photo by Kristina Folcik, AMC Photo Contest.

Staying in Touch

From shared staff and research grants to radio calls and rescues, it’s impossible to tell the history of AMC without the Mount Washington Observatory, and vice versa. Peter Crane, the Mount Washington Observatory Curator, doesn’t just record this history. He’s lived it. Before working at the Observatory, he was a ten-year AMC veteran, starting as a caretaker in Carter Notch Hut in 1978. In a 2006 article from the Hut Croo’s alumni association, the OHA, Crane says the skills he learned in his decade with AMC, from understanding the alpine environment to living in isolation, prepared him for his new job on the summit. In many ways, it’s a metaphor for the relationship between the two organizations.

“The trend is toward working more closely with some of the things that both organizations have been involved in for many, many decades. Hiker safety and hiker awareness. Protection of the environment. Climate awareness… It’s a big mountain, and there’s plenty of room for many organizations that are working for better experiences for the public and for the environment.”

Nothing is safe from the passage of time, even in the seemingly constant mountains. Observatory staff (and beloved “Obs” cats) come and go. The Pinkham Notch outpost that Joe Dodge helped turn into the center of White Mountain recreation is now named in his memory. Weather patterns shift and temperatures rise. But the partnership between AMC and the Mount Washington Observatory remains strong.

“It’s great that we’ve stayed in touch for 90 years,” says Crane.