This story was originally published in the Summer/Fall 2020 issue of Appalachia Journal.

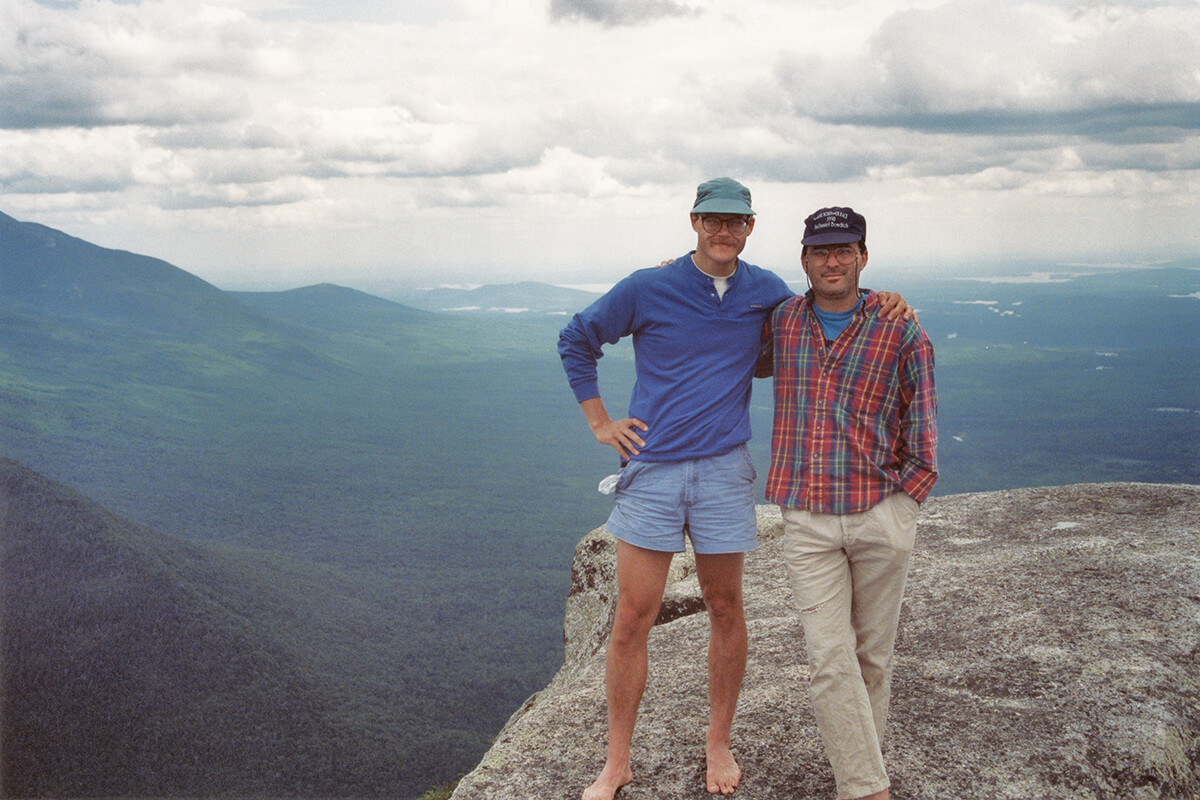

David Heald, left, with his friend Nat Bowditch on the south peak of Doubletop Mountain in Maine’s Baxter State Park, in 1991.

Last night’s rain clinging to the trailside underbrush soaked our thighs as we pushed up the lower part of the trail up Doubletop Mountain, in Maine’s Baxter State Park. The day was clear and bright, and a warming midsummer sun promised to dry us out when we reached the north peak.

This was our third trip to Baxter. On the first two excursions, we had stood exhilarated on Katahdin’s Baxter Peak. This year, 1991, we had begun exploring the surrounding mountains. We spent the night in a lean-to at Nesowadnehunk Campground and set out early the next morning for the summit of Doubletop.

Doubletop’s symmetrical shape and steep cliffs rise strikingly from the Nesowadnehunk valley, where the rutted perimeter road wends around the park.

Doubletop’s symmetrical shape and steep cliffs rise strikingly from the Nesowadnehunk valley, where the rutted perimeter road wends around the park. The view from the mountain’s twin peaks is of forests as far as the eye can see, ponds reflecting the sky, and to the east, mile-high Katahdin—the great mountain—above the east and west branches of the Penobscot River.

My hiking companion, Nat Bowditch, had been my dearest friend since childhood. These trips were our means of reconnecting, an open space apart from our increasingly busy lives. Quiet talks by the campfire, tramps through the woods, strenuous hikes up steep mountainsides, paddling the ponds of the park and, at the end of the day, bracing swims in frigid mountain streams, strengthened the bonds of love that drew us close together.

Nat and I saw no other hikers on our way up the slopes and shoulder of Doubletop. The crowds, no doubt, were amassing atop Katahdin. We reached the north peak in two hours’ time and ate cheese and bread, content to stretch out our legs and linger in the sun.

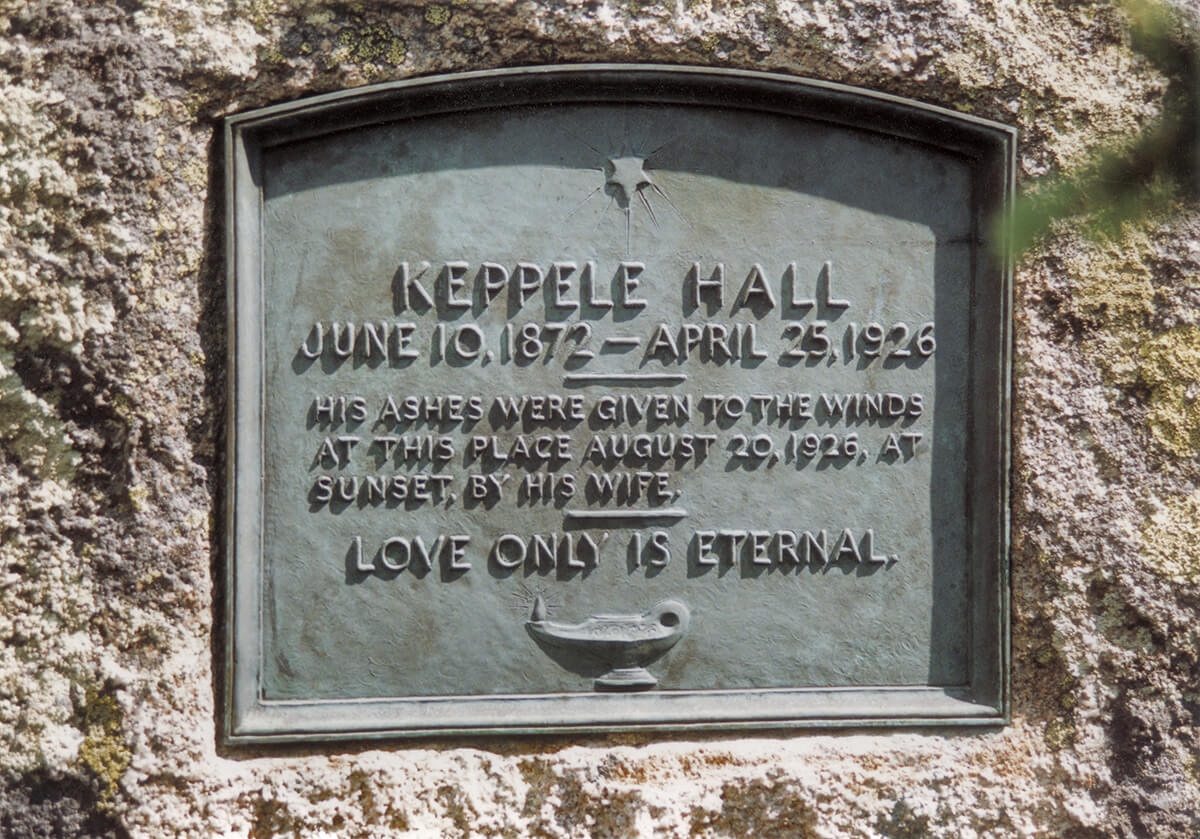

As we hiked into the saddle on our way to the south peak, I spotted a plaque affixed to a granite boulder just off the trail. A six-pointed star with rays extending outward crowned the inscription and, beneath the words, an oil lamp, evocative of undying light.

As we hiked into the saddle on our way to the south peak, I spotted a plaque affixed to a granite boulder just off the trail. A six-pointed star with rays extending outward crowned the inscription and, beneath the words, an oil lamp, evocative of undying light. The plaque faced south, and the sun, having risen high in the morning sky, illuminated its face, throwing the words into sharp relief:

KEPPELE HALL. JUNE 10, 1872 — APRIL 25, 1926. HIS ASHES WERE GIVEN TO THE WINDS AT THIS PLACE AUGUST 20, 1926, AT SUNSET, BY HIS WIFE.

And beneath this the words: LOVE ONLY IS ETERNAL.

I called Nat over. We gazed at the memorial, wondering who this man was and, even more so, who the woman was who scattered her husband’s ashes to the winds as the sun set and daylight began to fade. Many years later, by means of an online search that linked to the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women at Harvard University, I began to unfold the story of their lives.

This plaque on Doubletop memorializes an electrical engineer who died of influenza.

Keppele Hall was a Princeton graduate who became a successful electrical engineer and was a pioneer in the field of “scientific management,” a business model to enhance labor productivity. He married Fanny Southard Hay in 1896 in Trenton, New Jersey. The Halls lived briefly in Maine, where they apparently retained ties over the years, before moving to Ohio, eventually settling in Cleveland.

Fanny was a member of the Ohio delegation that marched in the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. After World War 1, she became involved in many Cleveland civic associations, her work focusing primarily on women’s penal reform. A member of the Women’s City Club, the League of Women Voters, and the Women’s Council for the Promotion of Peace, she was instrumental in organizing the 1924 women’s Peace Parade for the Prevention of Future Wars in Cleveland. She was the first American woman to serve as forewoman of a grand jury.

The Halls moved to New York City in 1926 where Keppele died from an outbreak of influenza. Having subsequently lost a great deal of money in the stock market crash of 1929, Fanny continued her civic involvement and became a home visitor in the Great Depression era Emergency Work Bureau. Later in life, she continued her interest in prison reform and was a frequent visitor at the Reformatory for Women at Framingham, Massachusetts. She died in Brattleboro, Vermont, in June, 1968, at the age of ninety-four.

I wonder if she climbed the tower. Was she alone? If not, who accompanied her? And what was said as she gave her husband’s ashes to the winds? Or was the call of a raven cruising the mountain slopes, and the rushing of the wind on the summit, sound enough for such a solemn occasion as this?

In 1926, the year of her husband’s death and the scattering of his ashes on that mountain summit in Maine, Fanny was 54. The trail to the south summit of Doubletop from the Kidney Pond Camps—then privately owned—covers just under four miles. The lower part of the route, because of the occasional confluence of stream and trail, is often wet and muddy. Higher up, the trail climbs a steep, timbered slope to the summit. The Appalachian Mountain Club Maine Mountain Guide notes that the traveling time from pond to summit via this trail—somewhat different than the one Fanny would have used—is three and a half hours. I imagine her climbing up there in the hiking attire women wore in the 1920s. She was carrying her husband’s cremains in her rucksack. In 1926, a fire lookout tower stood atop the north peak. I wonder if she climbed the tower. Was she alone? If not, who accompanied her? And what was said as she gave her husband’s ashes to the winds? Or was the call of a raven cruising the mountain slopes, and the rushing of the wind on the summit, sound enough for such a solemn occasion as this?

The walk down the mountain and back to the camps was through the waning light of dusk; perhaps a Swainson’s thrush serenaded her on the way. Cabin lamplight in the dark, and a dinner—such as only the old wilderness camps provided—welcomed her on her arrival back at the pond.

On that strikingly beautiful July day in 1991, Nat and I lingered on the mountain. After lunch, we made our leisurely way back down the north side of the mountain to our lean-to at Nesowadnehunk Campground.

Zen calls it the “great matter of life and death.” What is it? A woman standing on a mountain summit giving her beloved’s ashes to the winds. Just that.

For the Penobscot Tribe the Katahdin wilderness is a sacred place where the Spirit roams freely. Dennis Kostyk, in his film Wabanaki: A New Dawn, tells us, “To be with the mountain is to make a commitment to participate fully in life itself, to encounter the forces of life and to be in balance with them.”1

For all people, mountains embody a mystery beyond our control, just out of reach. Edwin Bernbaum wrote in Sacred Mountains of the World:

Floating above the clouds, materializing out of the mist, mountains appear to belong to a world utterly different from the one we know . . . Mountains have a special power to evoke the sacred as the unknown. Their deep valleys and high places conceal what lies hidden within and beyond them, luring us to venture ever deeper into a realm of enticing mystery. Mountains seem to beckon us, holding out the promise of something on the ineffable edge of awareness.2

As she gave her husband’s ashes to the mountain winds, perhaps Fanny felt herself standing at the ineffable edge of a great mystery.

As she gave her husband’s ashes to the mountain winds, perhaps Fanny felt herself standing at the ineffable edge of a great mystery. As she walked back down into the lowlands, perhaps she did so sensing a renewed commitment to embrace life and to serve others at the margins of society.

In my work as a hospice chaplain, I often find myself aware of a mystery just at the edge of awareness. But I stand not on a windy mountain summit but at the bedside of the dying. As a chaplain, my challenge is to give voice to that mystery; it is to stand hand-in-hand with grieving family and friends and to speak words that will invite depth and meaning.

For people aligned with no particular religious tradition or who are uncomfortable with the formulaic trappings of formal religion, I have had to find other words. The simple act of holding hands around the bedside of the dying gave birth to a different language, a new way of speaking. And what emerged was the language of love.

The simple act of holding hands around the bedside of the dying gave birth to a different language, a new way of speaking. And what emerged was the language of love.

But before words there is silence; to hold meaning, words must come forth from silence. In the silence I often gaze out the window at the sky or at the trees or am soothed and made still by falling snow or a gentle rain. I listen, too, for the song of birds or the “caw” of a crow passing over on its way to a perch in the woods. Or I listen to the breathing of others—whether family or friends—gathered in the room, or to my own breath. Coming to our senses grounds us in the moment.

And then these or similar words come:

This is a sacred time, a time of crossing over. We stand in awe at the edge of a great mystery. As we gather together in a circle of love, may our dear one be embraced by love. And may our lives be renewed by the love that we carry out into the world.

Love only is eternal.

Even as we minister to the dying, we are also mindful of their legacy. Each of us will leave a legacy of how we experience our death, of how we are able to be with our own dying. Joan Halifax, a Zen Buddhist priest and founder of the Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, writes of this legacy of how people cross through the ultimate rite of passage. In Being with Dying (Shambhala Publications, 2008), she recalls the story of Martin Toler, who died in the 2006 Sago Mine accident in West Virginia along with eleven other miners:

Slowly dying in the thickening air of the mineshaft, the oxygen wicked up with every breath, Toler used what little energy he had left to write a note of reassurance to those closest to him—and to the millions of us who later heard about it, too.

From deep inside the earth, Toler addressed the entire world, beginning his note: ‘Tell all—I see them on the other side.’ . . . He expresses for all of us the deep human wish that our connections will transcend the event of separation we suffer at the moment of death. ‘It wasn’t bad, I just went to sleep,’ the note continues, and scrawled at the bottom, with the last of his ebbing strength, are the tender, unselfish words “I love you.”

Halifax further explains that Toler’s last words honored the lesson that life is sacred and relationship holy.

In October, sixteen years after our hike up Doubletop, Nat’s wife called me from the intensive care unit of the local hospital. “Can you come?” she asked. “Nat is very sick.”

In October, sixteen years after our hike up Doubletop, Nat’s wife called me from the intensive care unit of the local hospital. “Can you come?” she asked. “Nat is very sick.” Nat’s father had died in August. After the memorial service, I was taken aback by how poorly Nat looked. Word eventually came that he had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer. He started on chemotherapy in preparation for a stem cell transplant that he hoped to have in Boston later that autumn. In the meantime, the chemotherapy had little effect; he developed a secondary condition resulting in congestive heart failure. Now the simple act of walking from his bedroom down the hall to the kitchen left him breathless.

View from Katahdin’s famous Knife Edge Trail.

During one of my last visits, sitting on the edge of Nat’s bed, I asked him, “What lifts your spirits? What gives you hope?” And he responded, “You do—my friends and family. I’ve got so much to live for. I love you, brother.”

Seeing the pain and grief in my eyes, Nat said, “Don’t worry . . . I’m OK.” When words failed, we would lie next to each other on the bed, holding hands. He died a few weeks later.

A week before his memorial service, I returned to Doubletop. My wife, Sukie, and I were staying at a cabin on Kidney Pond. I climbed the mountain alone this time and was feeling my age as I scaled the steep slope to the summit. In the low 50s down below, it was cold up top, a stiff wind blowing from the south. I found the flat expanse of granite where Nat and I stood arm in arm for our photo. A mourning cloak, a black butterfly with blue spots dotting the gold fringes of its wings, flitted across the ledge and was gone. After lingering for an hour or so in the sun sheltered away from the wind, I put my pack on and reluctantly headed back down the mountainside. Turning once to gaze up at the south summit, I spoke under my breath and then aloud, “I love you, my brother.”

After lingering for an hour or so in the sun sheltered away from the wind, I put my pack on and reluctantly headed back down the mountainside. Turning once to gaze up at the south summit, I spoke under my breath and then aloud, “I love you, my brother.”

Farther on, walking along an old logging road down below, the trail was littered with fallen yellow birch leaves and, here and there, a red maple leaf. The autumnal equinox was just hours away and the turning of the seasons was everywhere evident. Just before 4 o’clock, Sukie greeted me back at the cabin with a hug and the promise of hot tea.

A woman stands on a mountain summit at sunset, at the edge of a great mystery, and gives her beloved’s ashes to the winds.

On that same mountain, two friends stand shoulder to shoulder in the warming sun, smiling at the camera. A raven cries as it rides the gusts along the ridges and then veers off, out into the vast open sky.

If you enjoyed this story, you might consider subscribing to our Appalachia Journal.

The Rev. David Heald is an Episcopal priest. This essay is based on a sermon he gave in Scarborough, Maine, in 2014.

1 See wabanakicollection.com/videos/wabanaki-a-new-dawn/.

2 Edwin Bernbaum, Sacred Mountains of the World (University of California Press, 1998).