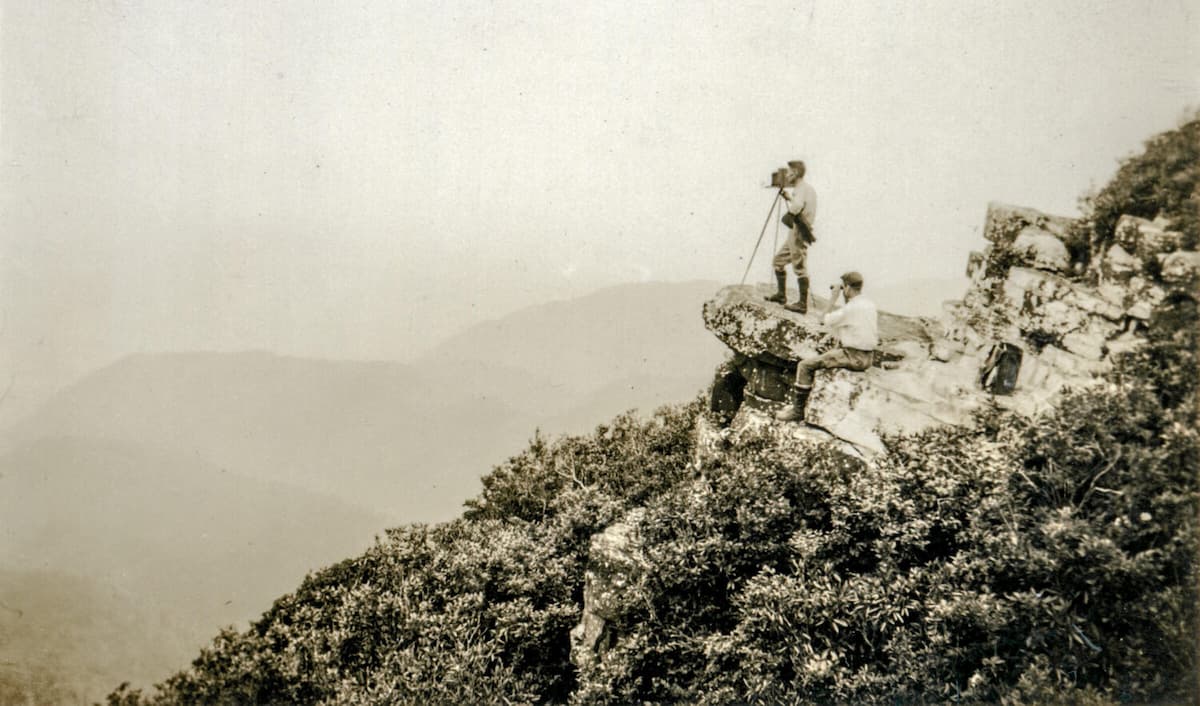

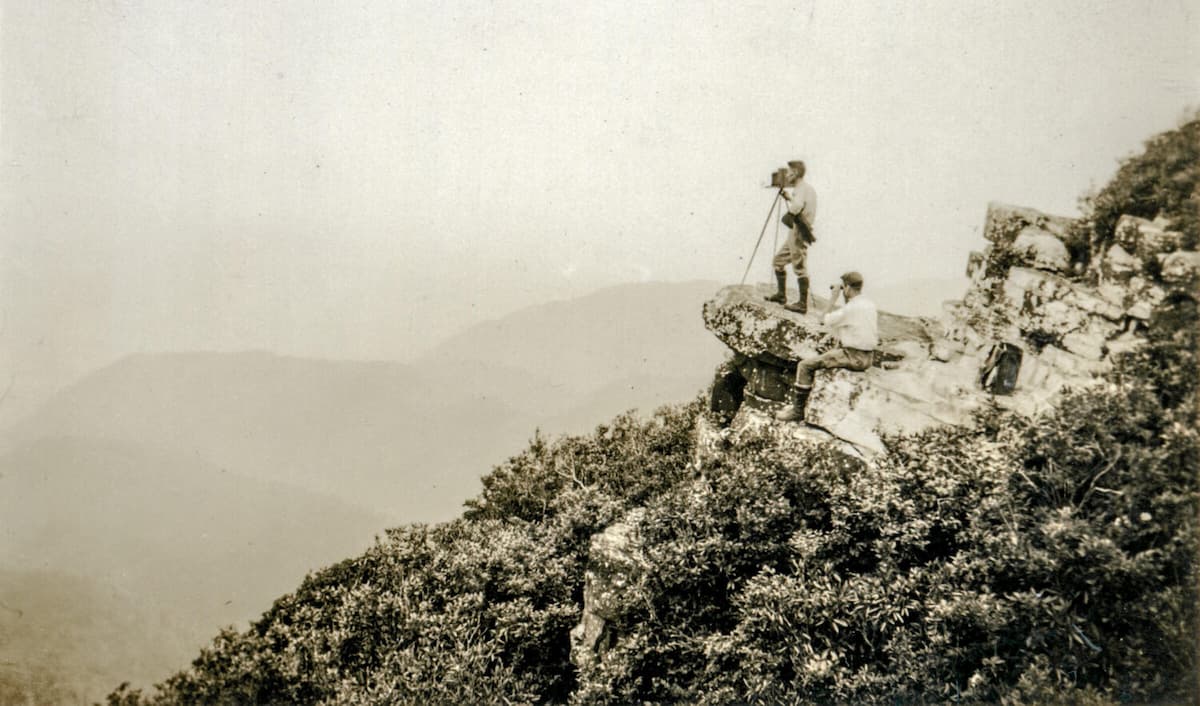

George Masa using his camera in North Carolina

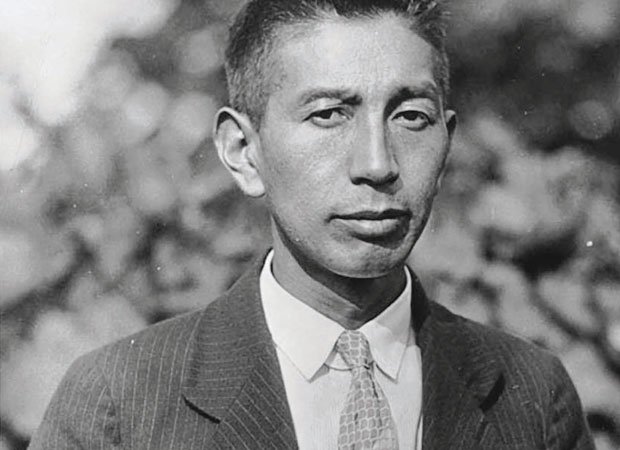

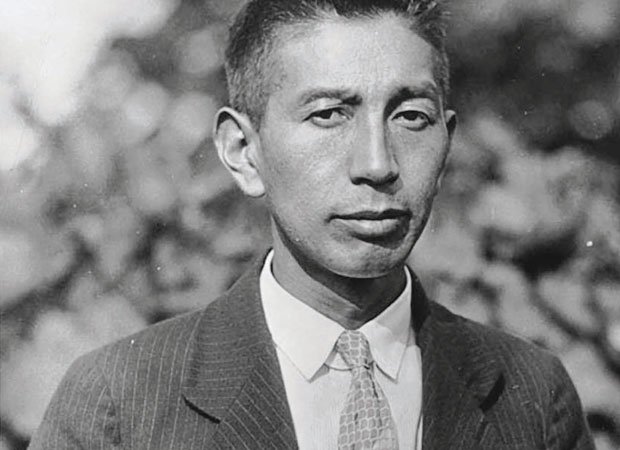

George Masa, a Japanese immigrant to the United States, is often referred to as the Ansel Adams of the East Coast. His work photographing and mapping the southern peaks of the Appalachian Trail proved crucial for the establishment of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the U.S. today. In the 18 years before his death, Masa captured photographs that beautifully depicted the Smoky Mountains, and used these images to convince philanthropists, politicians, and local community leaders to preserve the area. An avid mountaineer, Masa hiked several trails in the region, taking meticulous notes, and carrying half his body weight in photography equipment. Though Masa is one of the most influential conservationists in the region, much of his life and work remain unknown by the general public. Historians have been able to piece together parts of his life from his journal entries and accounts from friends and colleagues.

George Masa was born Masahara Iizuka in Osaka, Japan around 1889. He likely entered the U.S. in the early 20th century. At the time, rapid urbanization and industrialization brought a changing economy and great social disruption to Japan. As a result, many young men from farming and middle-class families emigrated to the United States in search of new opportunities. According to the Library of Congress, “between 1886 and 1911, more than 400,000 men and women left Japan for the U.S. and U.S.-controlled lands,” George Masa being one of them. Though most Japanese immigrants stayed in Hawaii and the Pacific Coast, Masa headed east on a train from San Francisco in 1915. His motivations for traveling east remain unknown.

George Masa

Masa arrived in Asheville, North Carolina and found a job in the laundry room of the Grove Park Inn, where he was quickly promoted to a valet position. Masa became a popular figure among the wealthy and influential guests and started making valuable connections. He often developed film on behalf of the guests and shared his own photos – showcasing his photographic skills.

However, in the early 20th century, anti-Japanese sentiment had already been forming. Many American citizens were suspicious of the newly immigrated Japanese and feared the “yellow peril.” Though the worst of anti-Japanese xenophobia occurred after Masa’s death during World War II with the establishment of Japanese Internment Camps, discrimination and prejudice were still rampant at the start of the century. Masa experienced this discrimination first hand in 1916 when he told Fred Seely, the manager of the Grove Park Inn, that he planned on leaving in search of an opportunity in a bigger city. Seely grew suspicious that Masa might be involved in espionage and reported him to the U.S. Department of Justice, citing his photographs and his planned departure as evidence.

These claims of espionage proved baseless and Masa continued to work at the Grove Park Inn, despite mistreatment from his employer. In his spare time, Masa joined a hiking club and spent a lot of time surveying and photographing the peaks and valleys of the Smoky Mountains. In 1918, he finally left the Grove Park Inn and took a job with a local photographer, Herbert Pelton. Together, Pelton and Masa formed a business partnership and started a studio called The Photo Craft. Less than a year later, Pelton moved to Washington D.C., leaving Masa as the sole owner of the studio.

Santeethlah Lake as captured by George Masa in 1928

His studio quickly gained local importance and the Chamber of Commerce started using his work to promote the area. As his business grew, Masa spent more and more time in the Smoky Mountains, often in the backcountry for days and weeks at a time. On these adventures, Masa met like-minded people like Horace Kephart, a local journalist, nature lover, and author who had already written two books about the Smoky Mountains. After witnessing firsthand the devastation caused by industrial-scale logging, Kephart was determined to turn the area into a National Park. Masa quickly joined him in his efforts and the two of them became best friends, working closely together – Masa taking pictures and Kephart writing articles – to preserve the beautiful landscape they both admired.

Masa and Kephart recorded every stream, mountain, and valley that fell within the proposed park boundary, often consulting the Cherokee people about the names. They trekked into the mountains to draw sketches, meticulously label photos, and measured the distance of trails. Masa made his own measurements with a DIY odometer that he created with the front half of a broken bicycle. During these long trips, Masa often sacrificed himself for his work, using his shelter to protect his equipment and to prevent his photographs from getting ruined, while he spent many sleepless nights in the rain.

In 1929, when the Great Depression hit the United States, Asheville closed its banks and Masa lost all of his savings. Despite this setback, he continued mapping and photographing the southern portion of the Appalachian Trail. He leveraged the connections that he gained at the Grove Park Inn and sent his photographs of the proposed park land to former first lady, Grace Coolidge and John D. Rockefeller Jr. After seeing Masa’s photographs, Rockefeller Jr. donated five million dollars to help purchase the lands for what would become the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. According to Janet McCue, a biographer of Masa, “the park might have never happened” without this donation.

The Chimneys as captured by George Masa

Unfortunately, neither Masa nor Kephart was able to see the opening of the park. In 1931, Horace Kephart was killed in a car accident. Two years later, in 1933, Masa fell ill. Unable to pay for the proper medical attention, he died alone in a county hospital from complications of the flu. However, their impact has not been forgotten. In 1934, one year after Masa’s death, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established. Today, it receives over 12 million visitors annually. In 1935, conservation hero Myron Avery chose one of Masa’s images for his Scientific American article that convinced authorities to finish the southern part of the Appalachian Trail.

Masa’s fellow hiking members also wanted his life’s work to be memorialized in the park. On June 4, 1939, James H. Caine of the Asheville Times wrote: “When George Masa died some six years ago there was a movement afoot to fittingly recognize what he had done to preserve in pictorial history the scenic grandeur of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. But like Mark Twain’s weather, nothing has been done about it.” That changed in 1961, when a 5,685 foot peak in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was named Masa Knob – a fitting honor for someone who selflessly dedicated his life to preserve an area that millions are able to enjoy today.

More of Masa’s photos can be found here.