Thru-hiker Kim Shaffer makes her way along the Appalachian Trail near AMC’s Mohican Outdoor Center in New Jersey’s Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Throughout the history of the Appalachian Trail, tens of thousands have made the nearly 2,200-mile trek.

It’s been a century since regional planner Benton MacKaye first published his vision for an Appalachian Trail (A.T.)—a recreational route “to establish a base for a more extensive and systematic development of outdoors community life.” What transpired since 1921 is a testament to human ingenuity, volunteerism, teamwork, and love of the outdoors—values that thrive along the 2,192-mile route between Maine and Georgia today. What follows is a brief photo history of the A.T., along which the Appalachian Mountain Club maintains more miles of trail than any organization. Many thanks to the AMC Library and Archives, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, and the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College for their assistance compiling this history and these images.

COURTESY OF DARTMOUTH LIBRARY

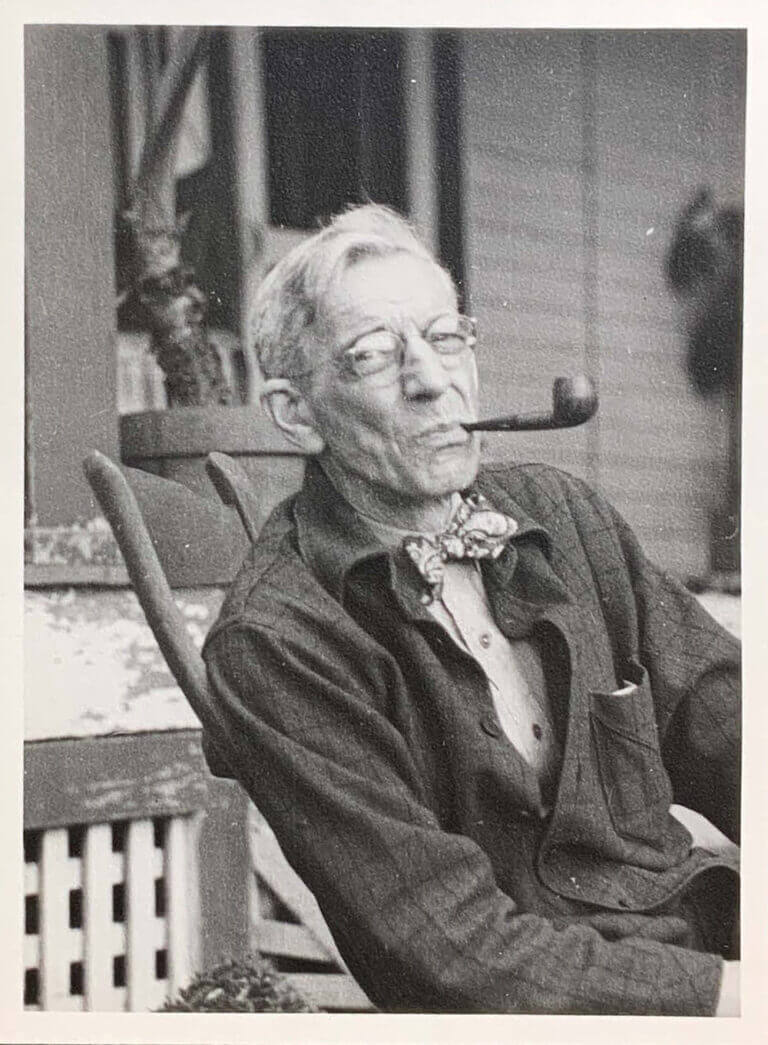

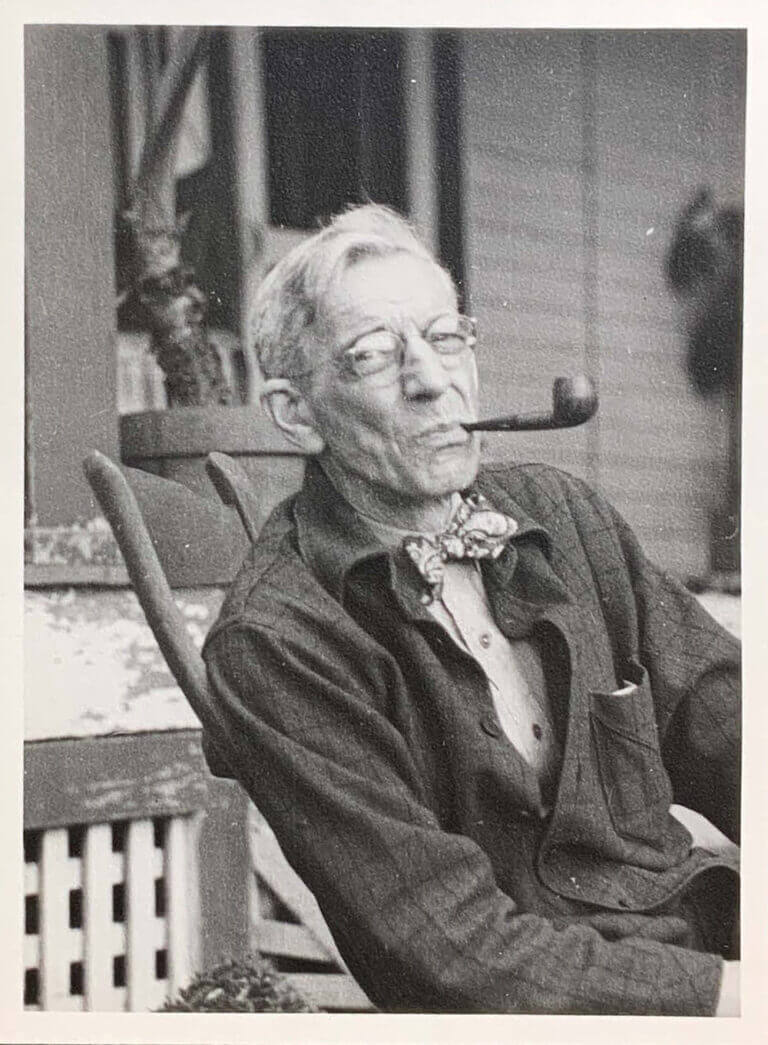

Regional planner Benton MacKaye, shown here later in life, is considered the “father of the Appalachian Trail.”

COURTESY OF DARTMOUTH LIBRARY

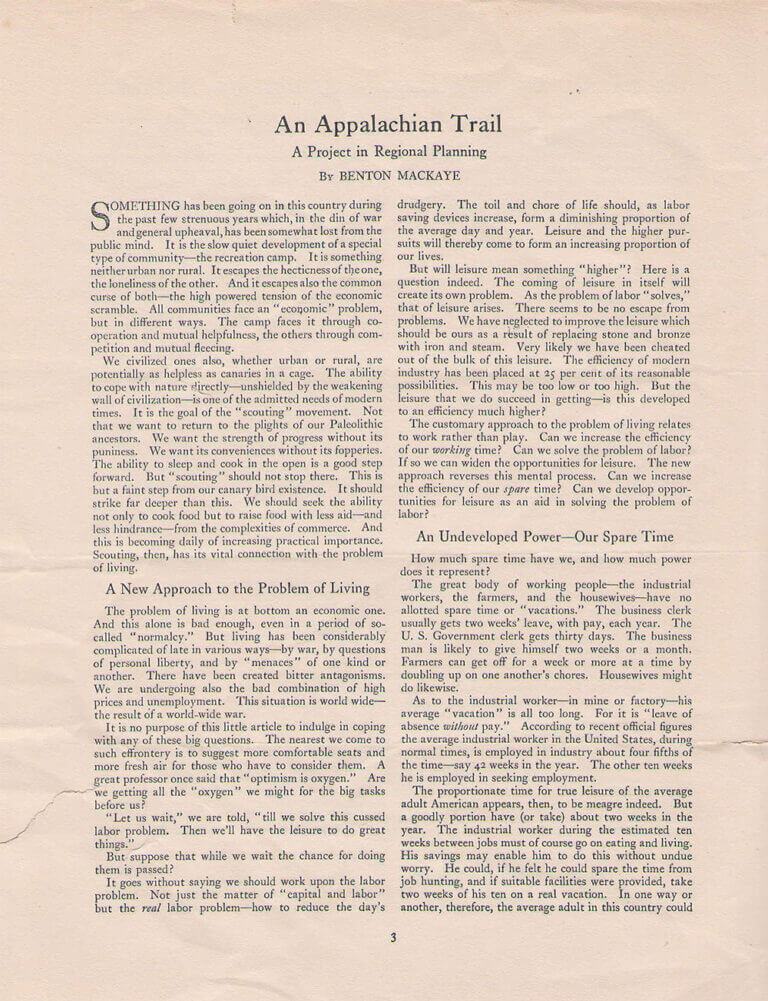

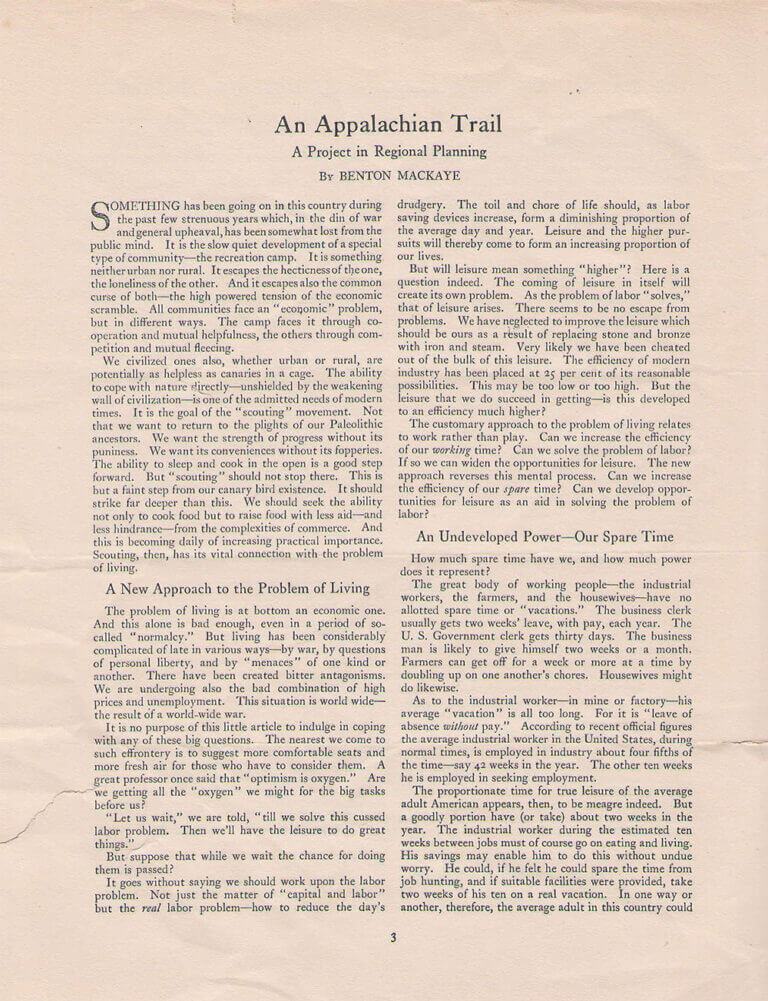

MacKaye first published his vision for a contiguous hiking trail between New England and the American South in the October 1921 issue of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. (Read MacKaye’s entire vision here.)

COURTESY OF DARTMOUTH LIBRARY

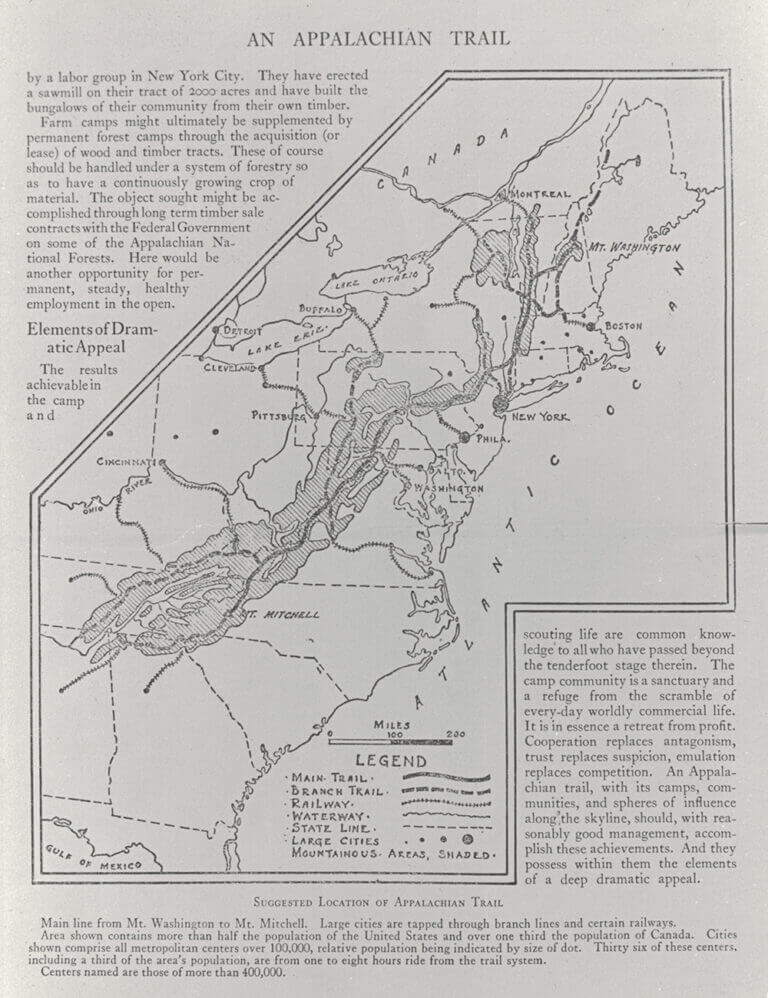

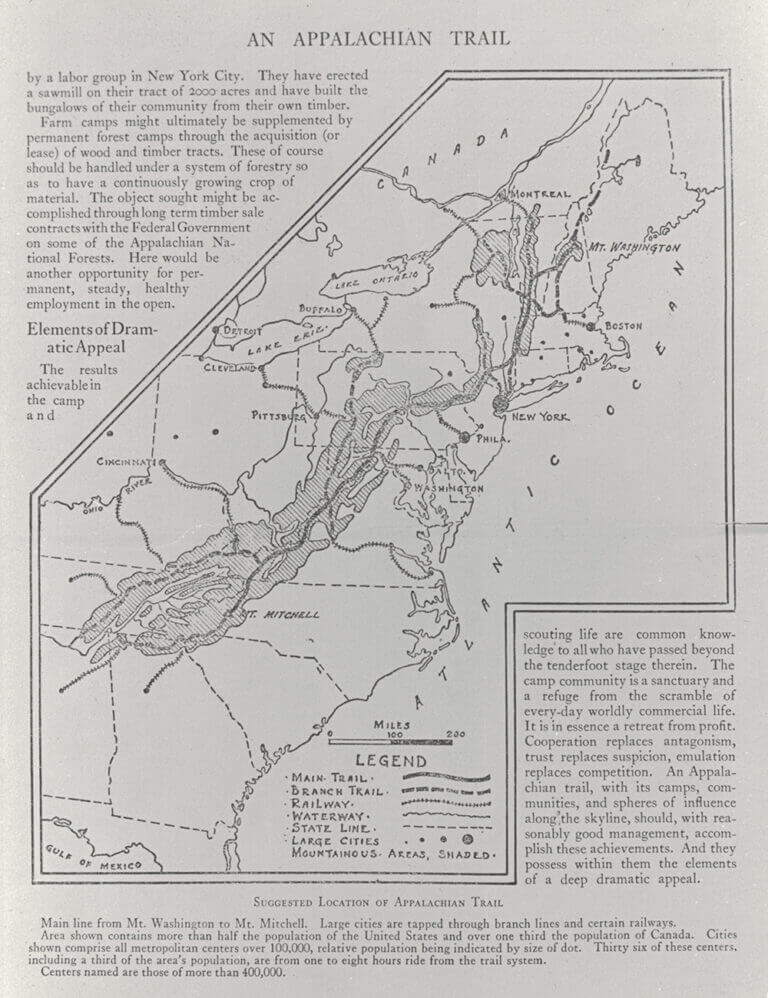

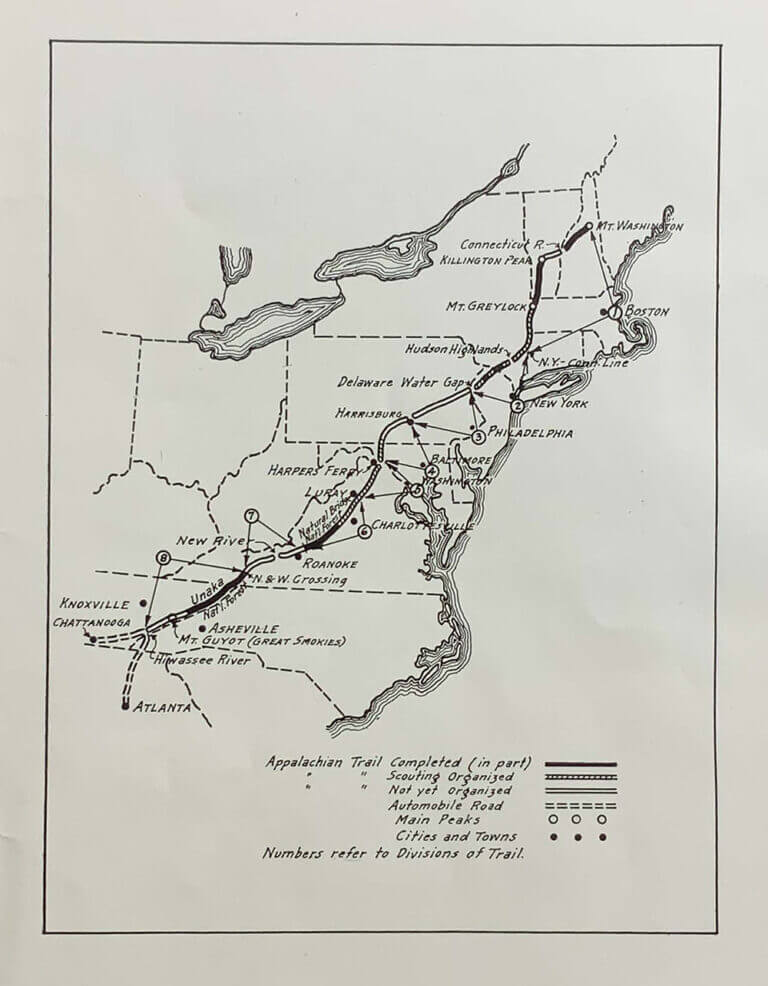

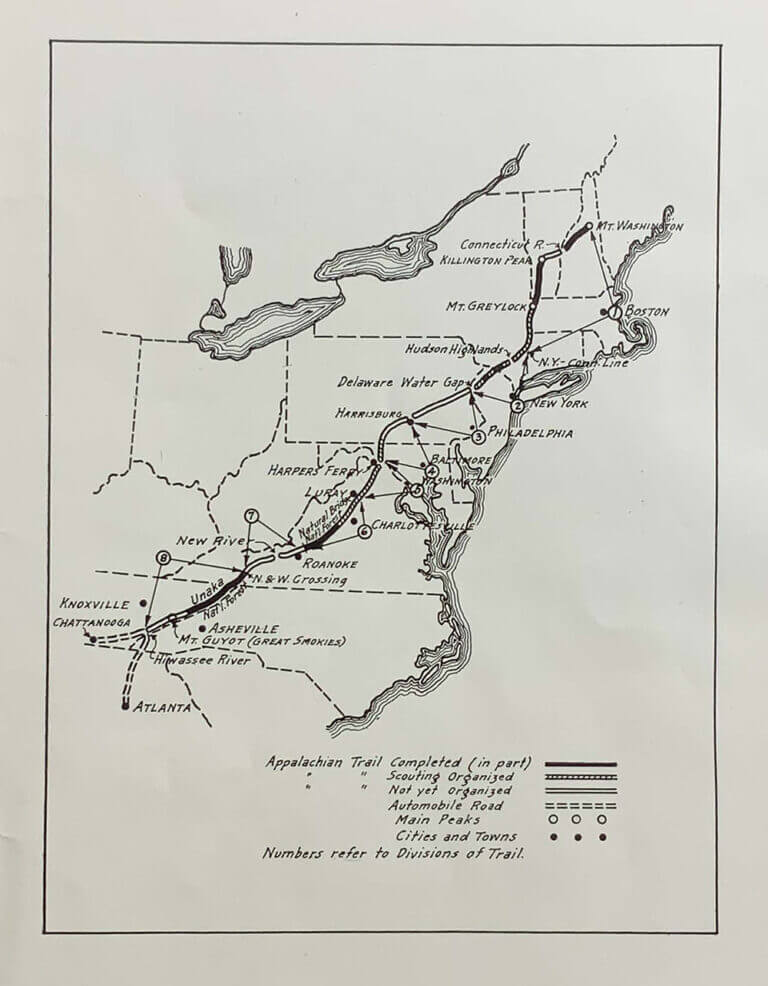

MacKaye originally imagined an unbroken trail from New Hampshire’s Mount Washington to North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell (with branch trails extending north to Katahdin and south into Georgia). “The beginnings of an Appalachian trail already exist,” he wrote in his Journal of the American Institute of Architects article, which was republished in the New York Times. “They have been established for several years—in various localities along the line. Especially good work in trail-building has been accomplished by the Appalachian Mountain Club in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and by the Green Mountain Club in Vermont.”

COURTESY OF DARTMOUTH LIBRARY

MacKaye envisioned a series of side trails connecting major metropolitan centers to the Appalachian Trail, as seen in this 1922 map published in AMC’s Appalachia journal. Using his extensive professional and social network, MacKaye promoted his trail wherever he could and built enough momentum to call the first meeting to plan for its construction in 1925.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

The first Appalachian Trail Conference was called in 1925, with an objective of “organizing a body of workers (representative of outdoor living and of the regions adjacent to the Appalachian range) to complete the building of the Appalachian Trail.” Presiding over the conference meeting was the ATC’s inaugural chair, Major William A. Welch, who had been instrumental in forming New York’s state parks system. Welch designed and made the first A.T. trail markers and may have come up with the “Maine to Georgia” slogan.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

But while planning for and promotion of the Appalachian Trail would continue, actual progress to the trail’s construction was slow-going. It wasn’t until Arthur Perkins (pictured above)—a retired lawyer, police court judge, and officer with the AMC Connecticut Chapter—officially took over leadership of the A.T. project in 1927 that the project began to gain steam. For one, the ATC wrote a new organizational mission: to “promote, establish and maintain a continuous trail for walkers, with a system of shelters and other necessary equipment…as a means for stimulating public interest in the protection, conservation and best use of the natural resources within the mountains and wilderness areas of the East.” A young Connecticut native and Harvard Law School graduate named Myron Avery took on much of the field work plotting routes, organizing clubs, recruiting volunteers, and ultimately cutting, blazing, and printing guide books for the new trail.

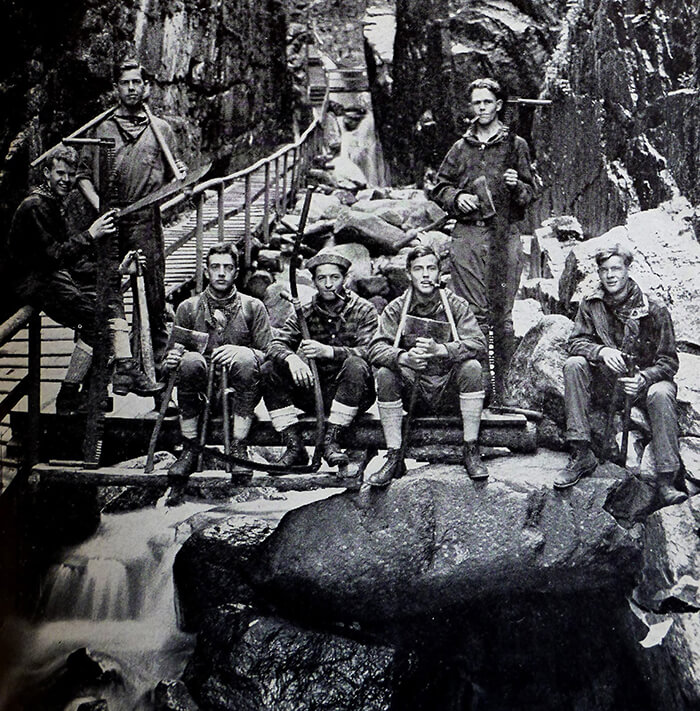

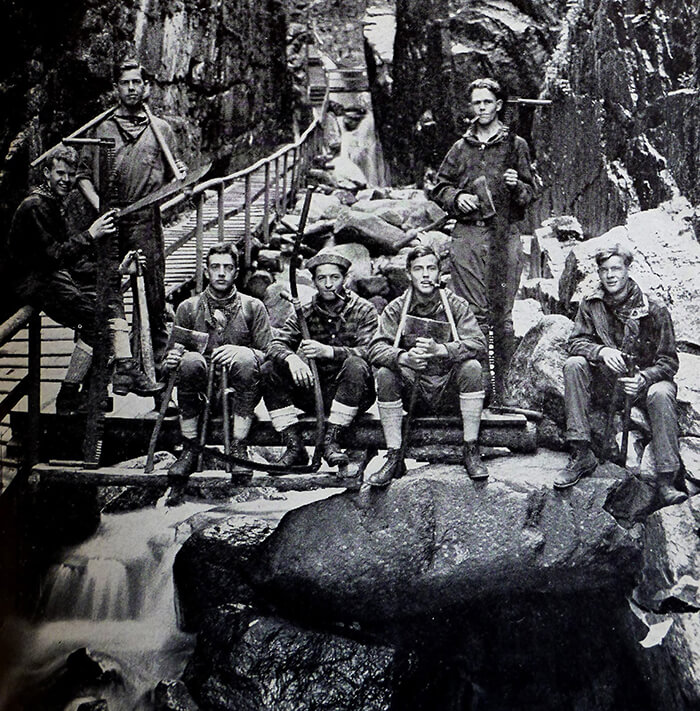

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

By the time Perkins and Avery had breathed new life into the A.T. project in 1928, at least 500 miles of trail were open to hikers—located mainly in New York and New England and maintained by local outdoor clubs like AMC. Pictured: members of AMC’s Professional Trail Crew in 1924, which would be instrumental in maintaining portions of what would become the A.T. in New Hampshire.

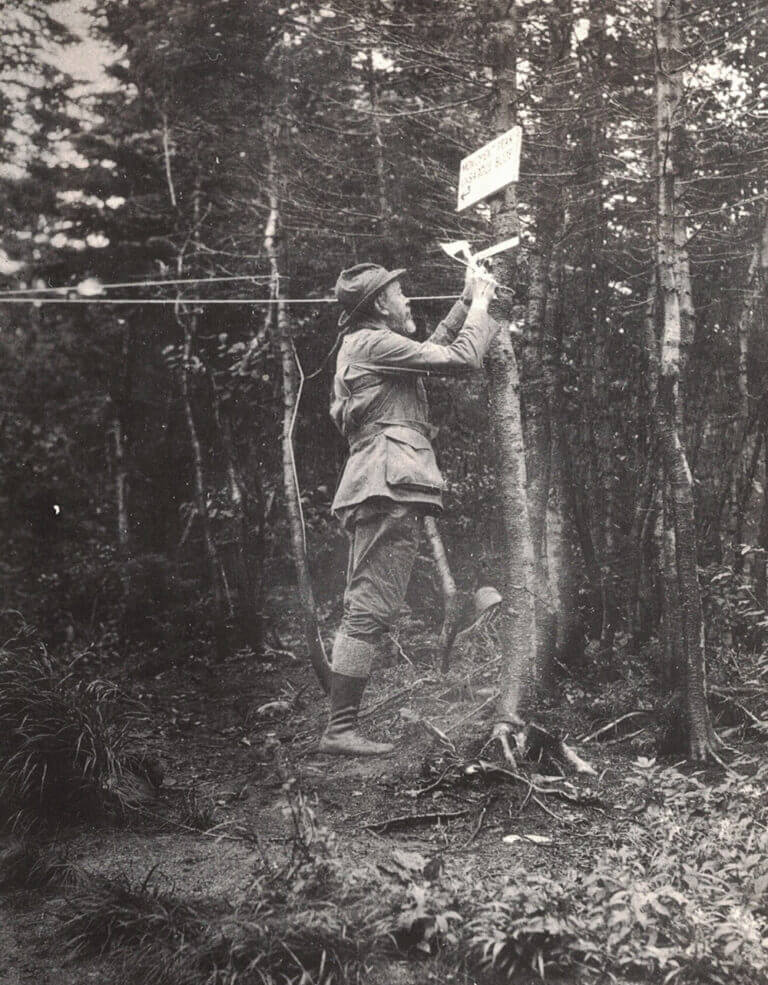

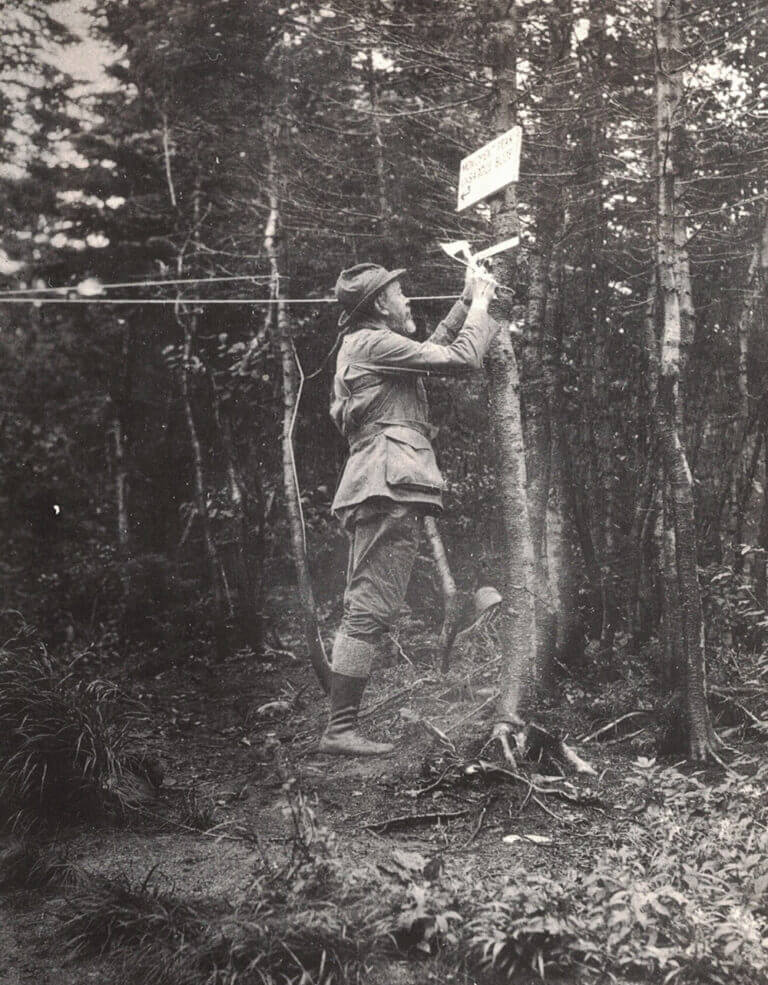

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

Early trail blazers, working with state wardens, ventured deep into the Maine backcountry to cut and blaze the A.T. there.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

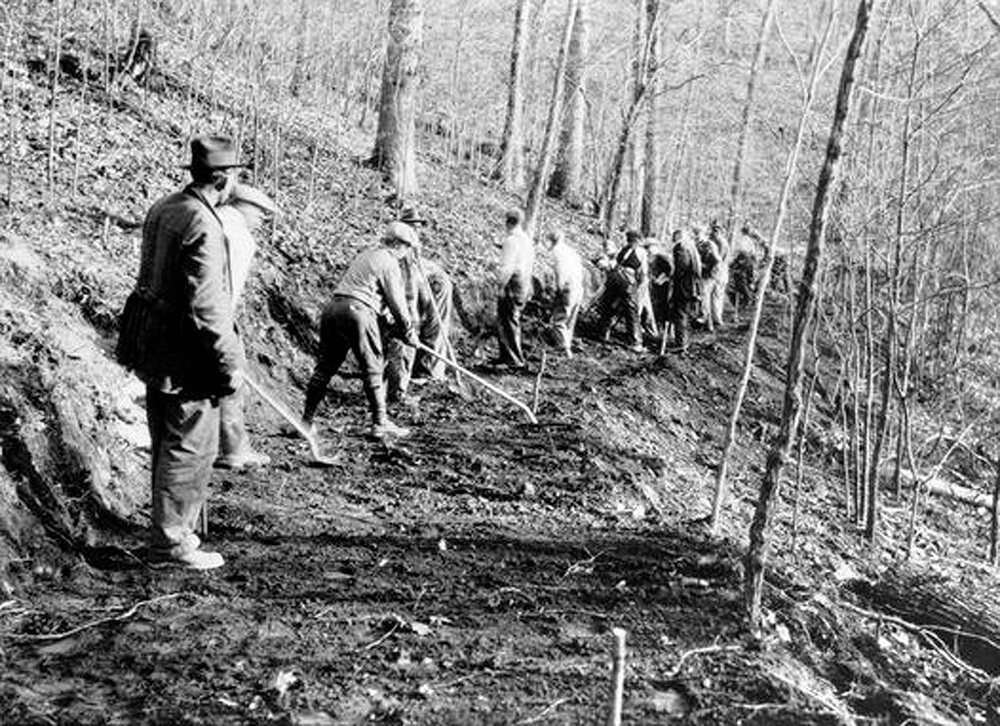

Volunteers help cut the A.T. near Finnerty Pond, in Washington, Mass., in April 1930.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

Progress on the A.T. got an assist in 1933 with the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a voluntary public work relief program that employed unmarried men ages 18 to 25. The CCC, along with the U.S. Forest Service, was responsible for much of the progress on the physical trail during the 1930s.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

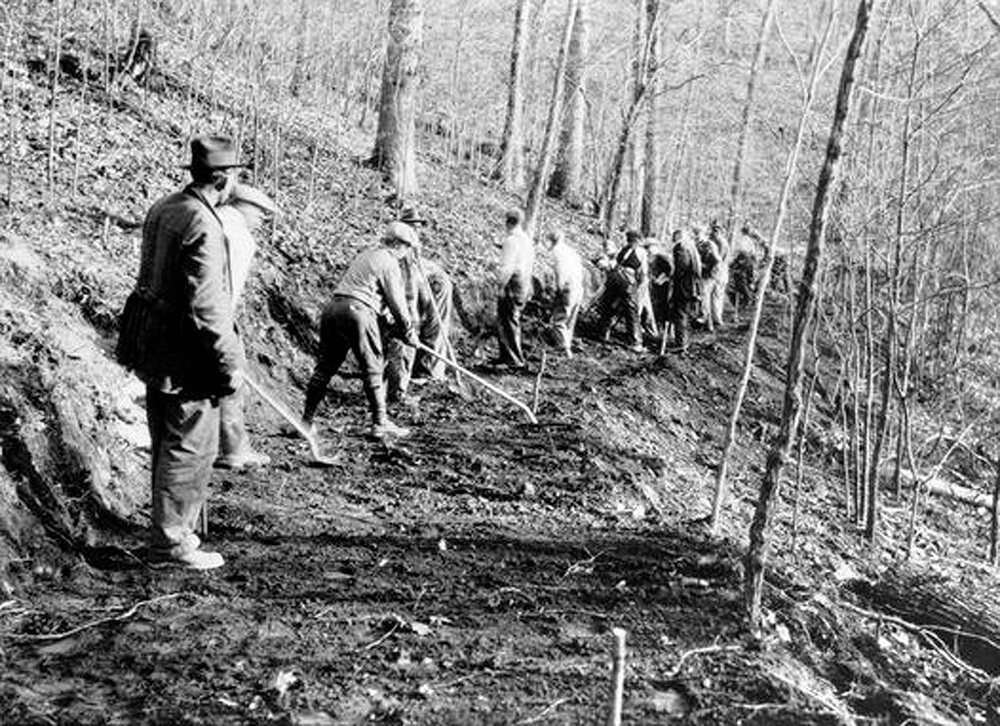

Civilian Conservation Corps members clear a section of the A.T. in Shenandoah National Park in Virginia.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

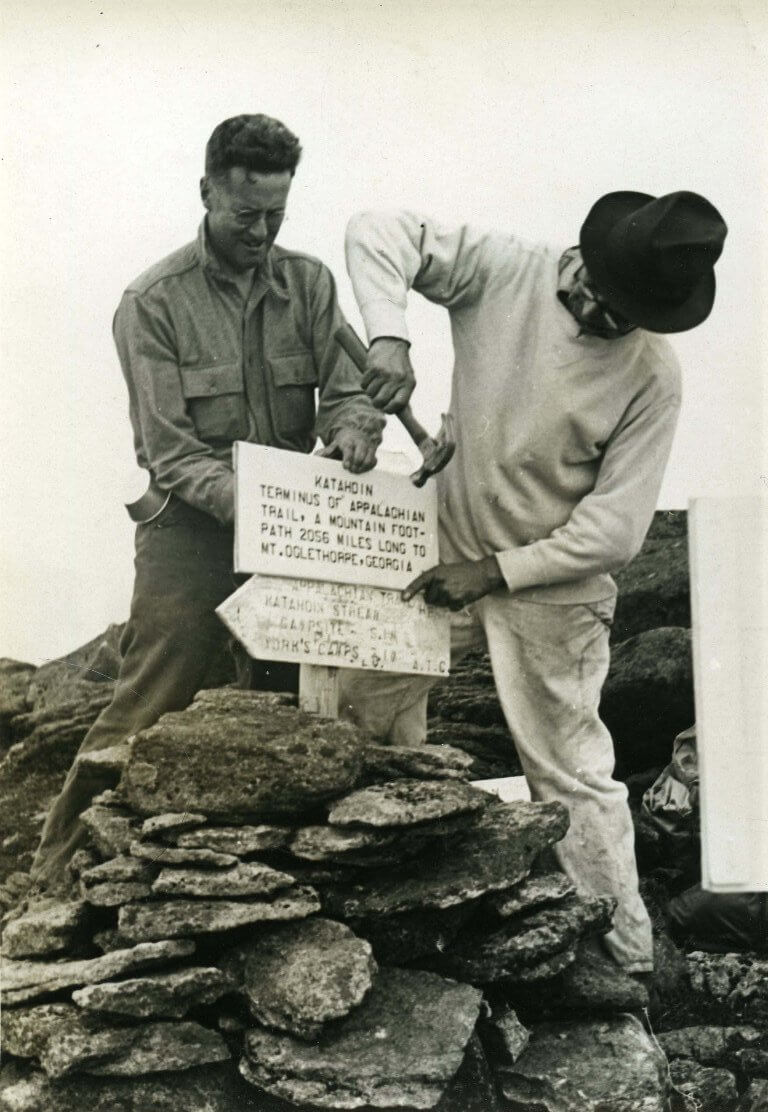

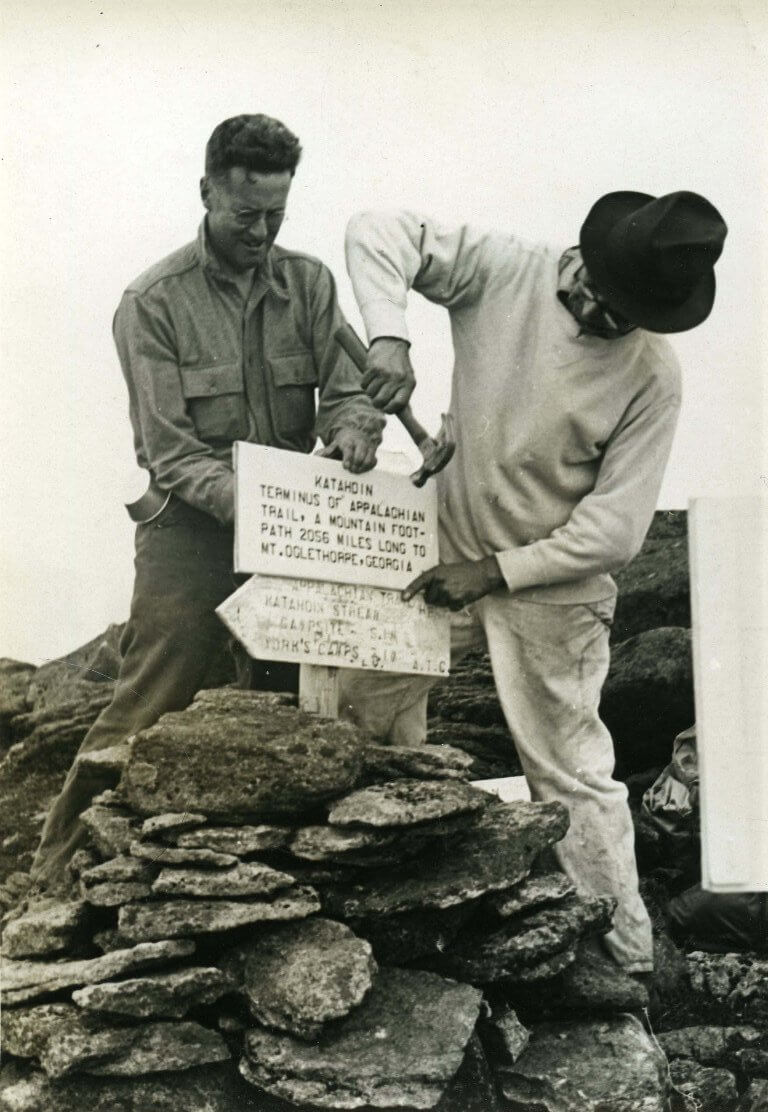

A crew takes up the first sign to Katahdin’s summit in 1933. Leading the group is Myron Avery—at that point the chair of the ATC—followed by longtime ATC secretary Marion Park and others from the Potomac A.T. Club.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

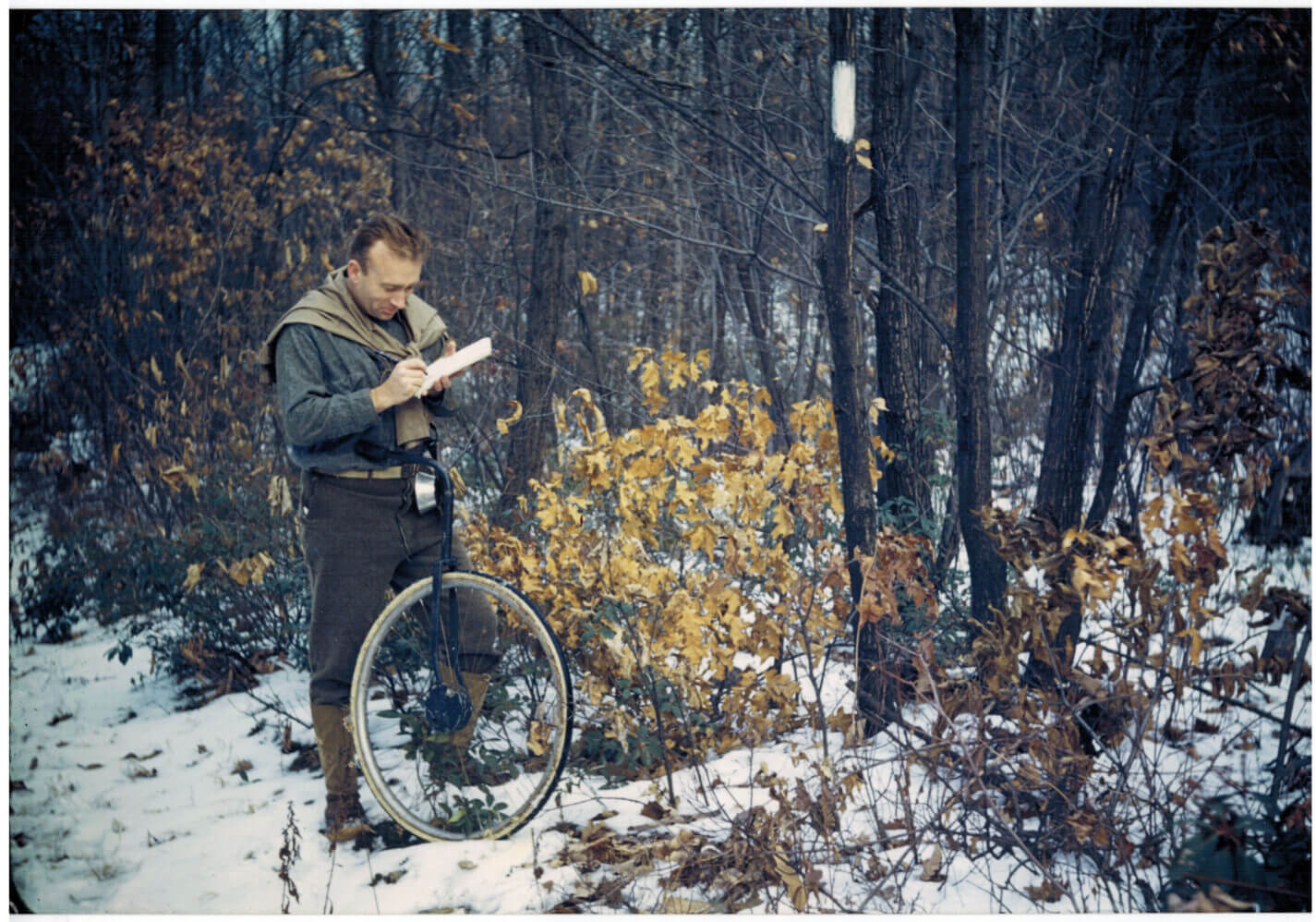

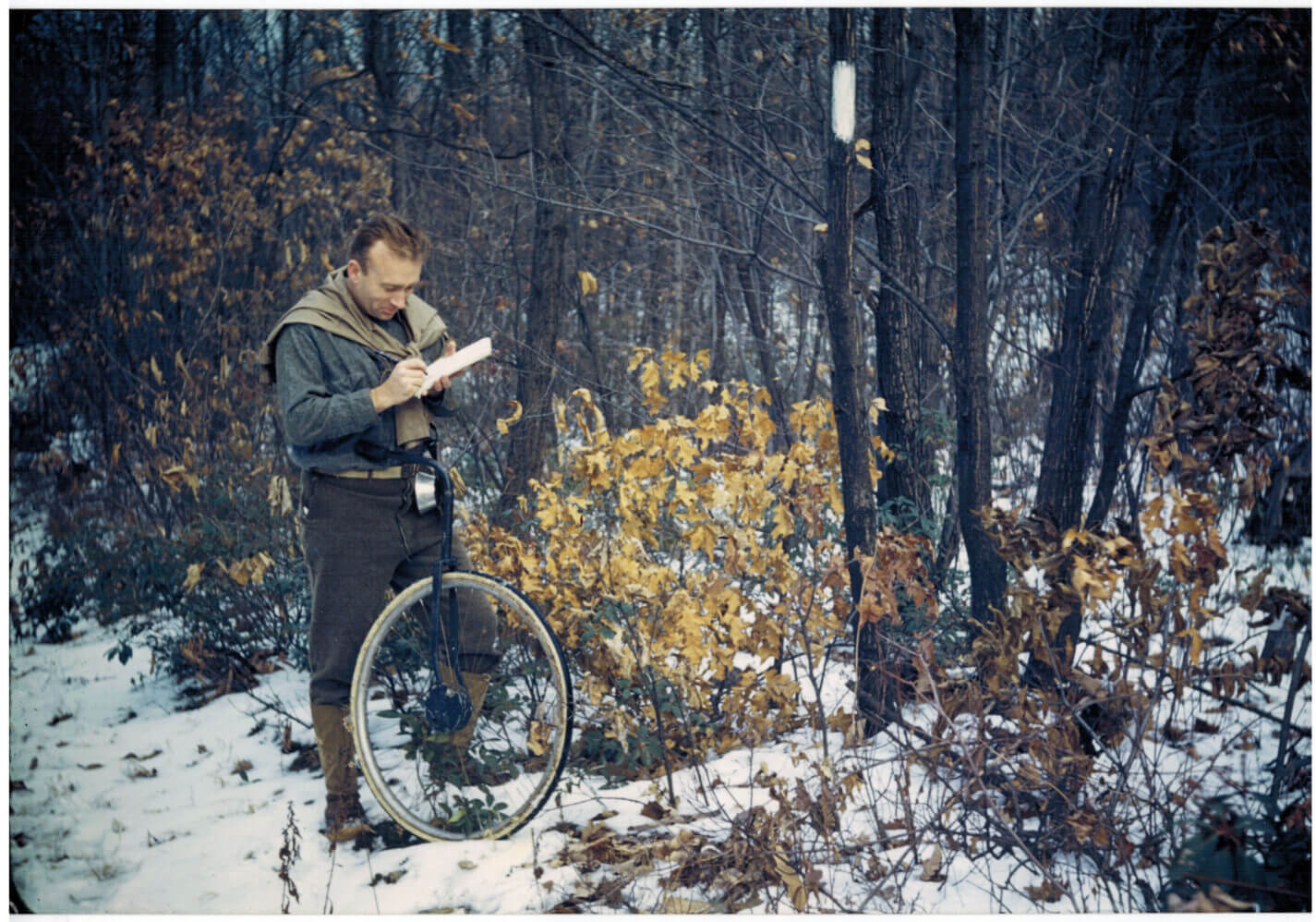

Avery did much of the A.T. trailblazing in the Mid-Atlantic himself. Here he is measuring a stretch of trail in Pennsylvania.

COURTESY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

In 1934, ATC volunteers affix the first sign at Katahdin’s summit declaring it as a terminus of the Appalachian Trail. A third variation of the sign would be mounted in 1939.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

Nearly two decades after its conception, the A.T. was declared finished in 1937. These hikers make their way along the Crawford Path, part of the A.T. in New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest, near the Mizpah Springs Shelter.

COURTESY OF APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

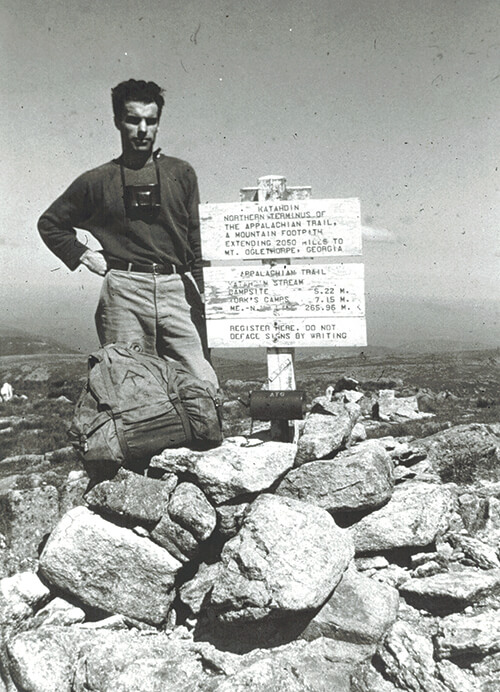

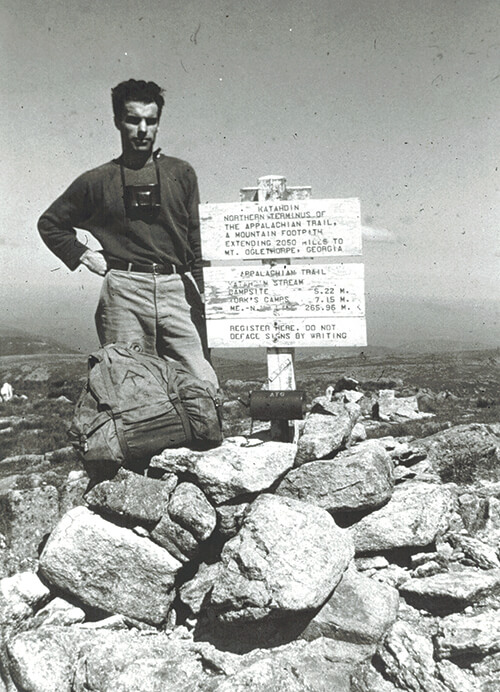

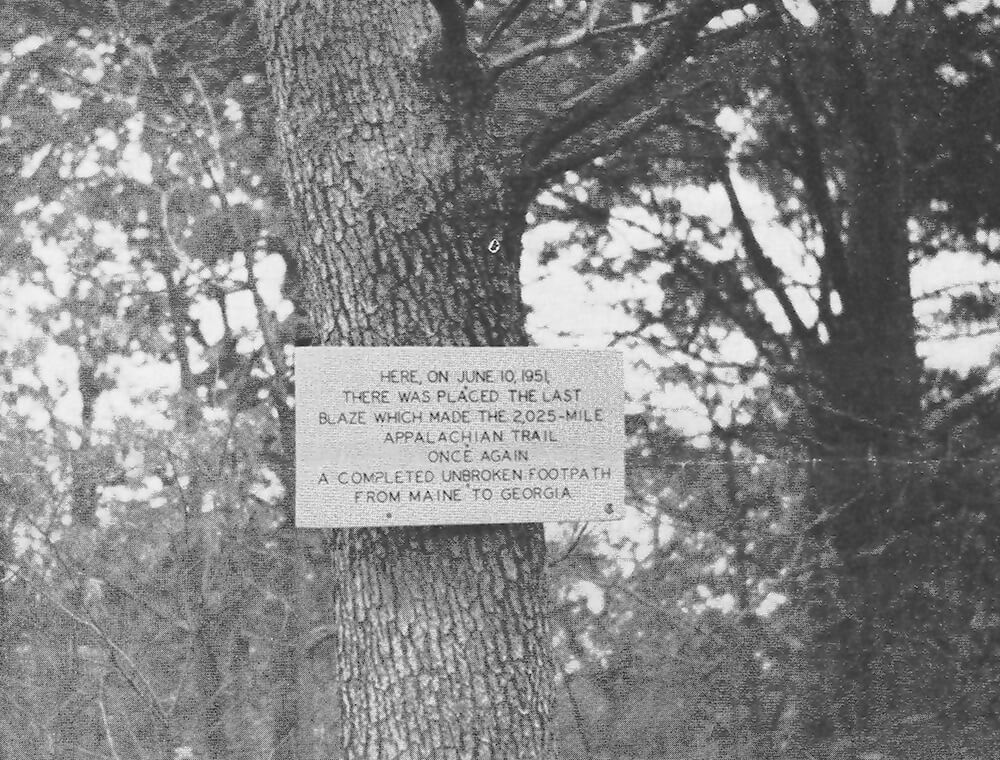

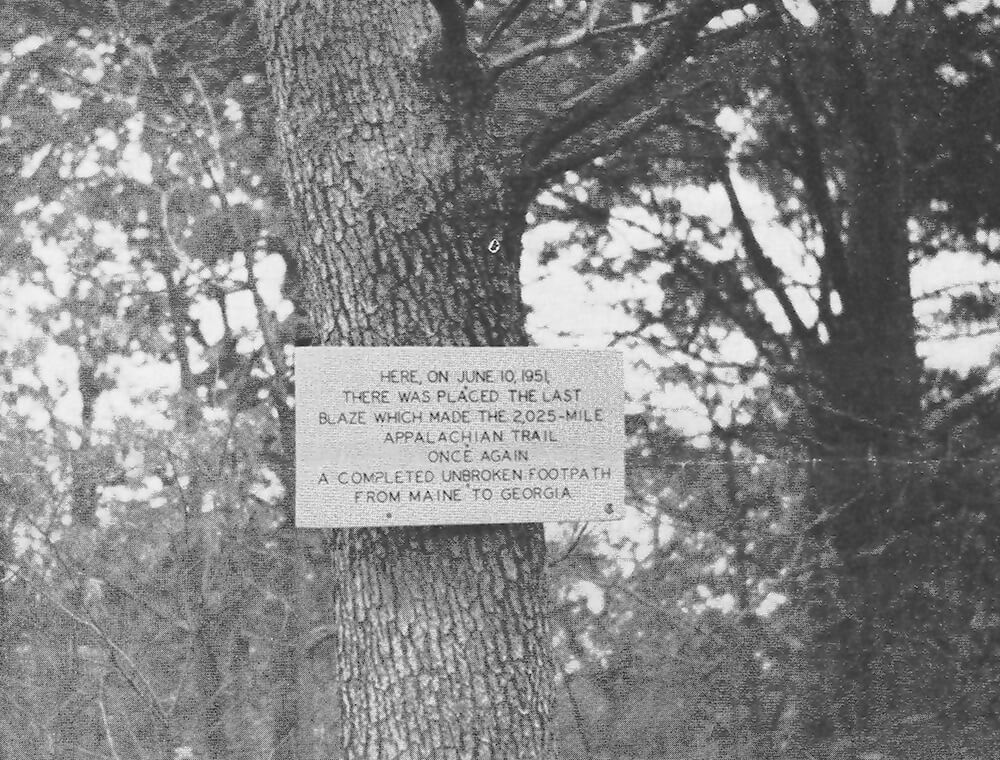

In 1948, Earl Shaffer became the first person to report thru-hiking the entire Appalachian Trail. In measuring the trail more than a decade earlier, Avery is considered the first to section-hike the entire route over the course of eight or nine years.

COURTESY OF APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY

With nearly all able-bodied men called away to serve in World War II, many sections of the Appalachian Trail fell into disarray from lack of maintenance during the 1940s. This sign was placed in Virginia at the trail’s official reopening in 1951 following four or five years of repair work along the A.T.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

A year after its reopening, in 1952, Mildred Norman—a mystic and activist later known as Peace Pilgrim—became the first woman to thru-hike the A.T. in one season.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

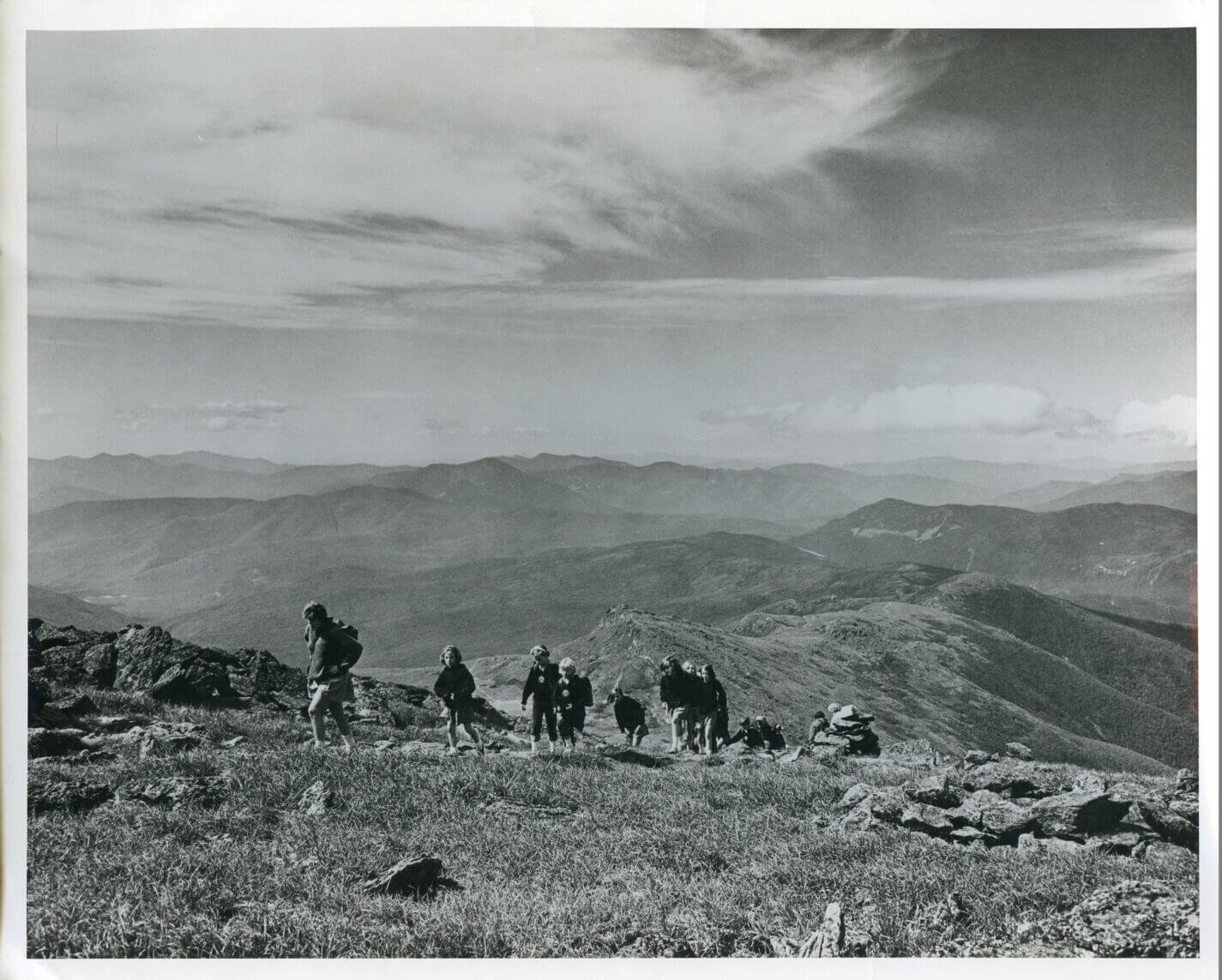

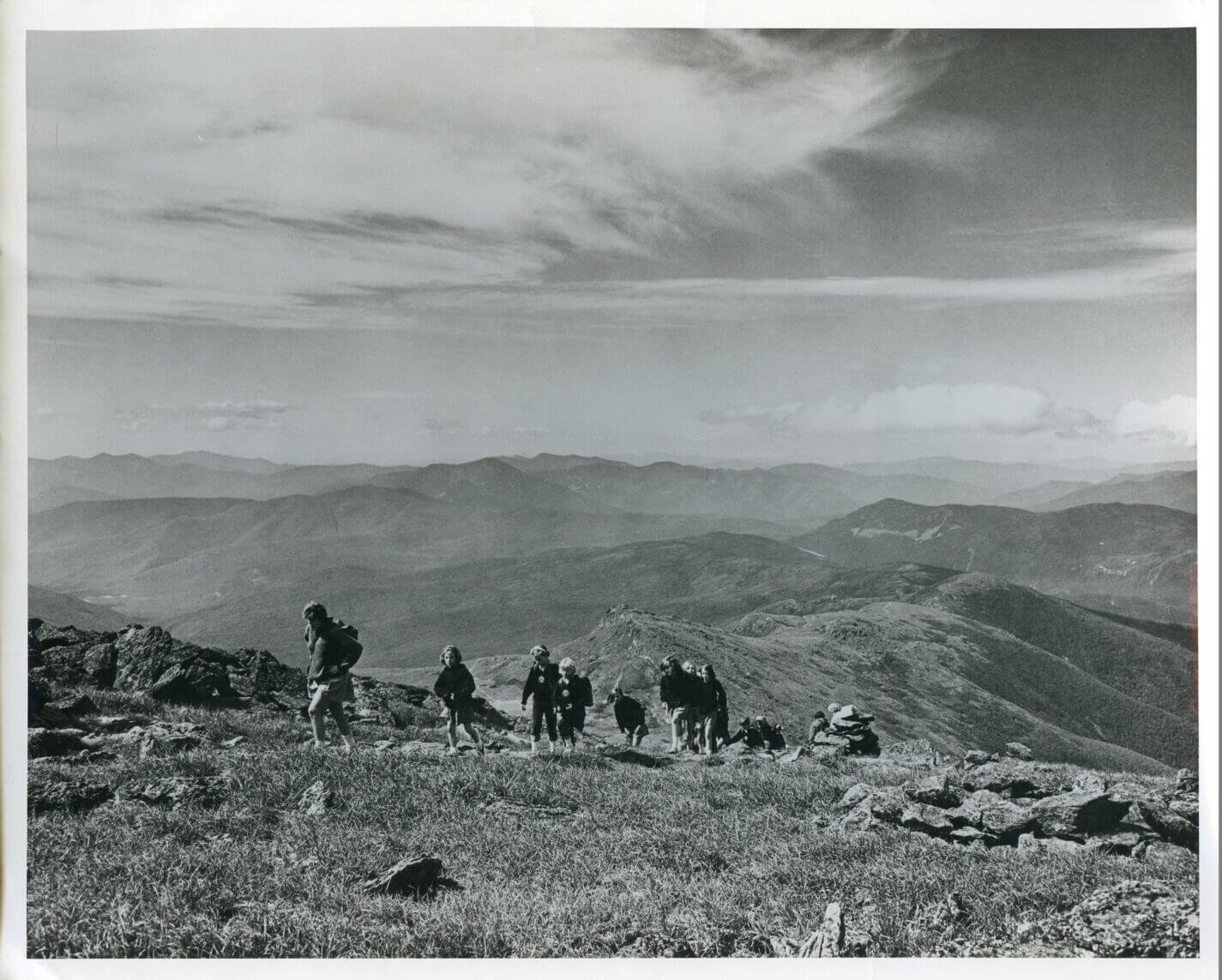

The hiking boom of the 1960s and 1970s brought more hikers to the A.T. than ever before. These hikers make their way along the Crawford Path in New Hampshire.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

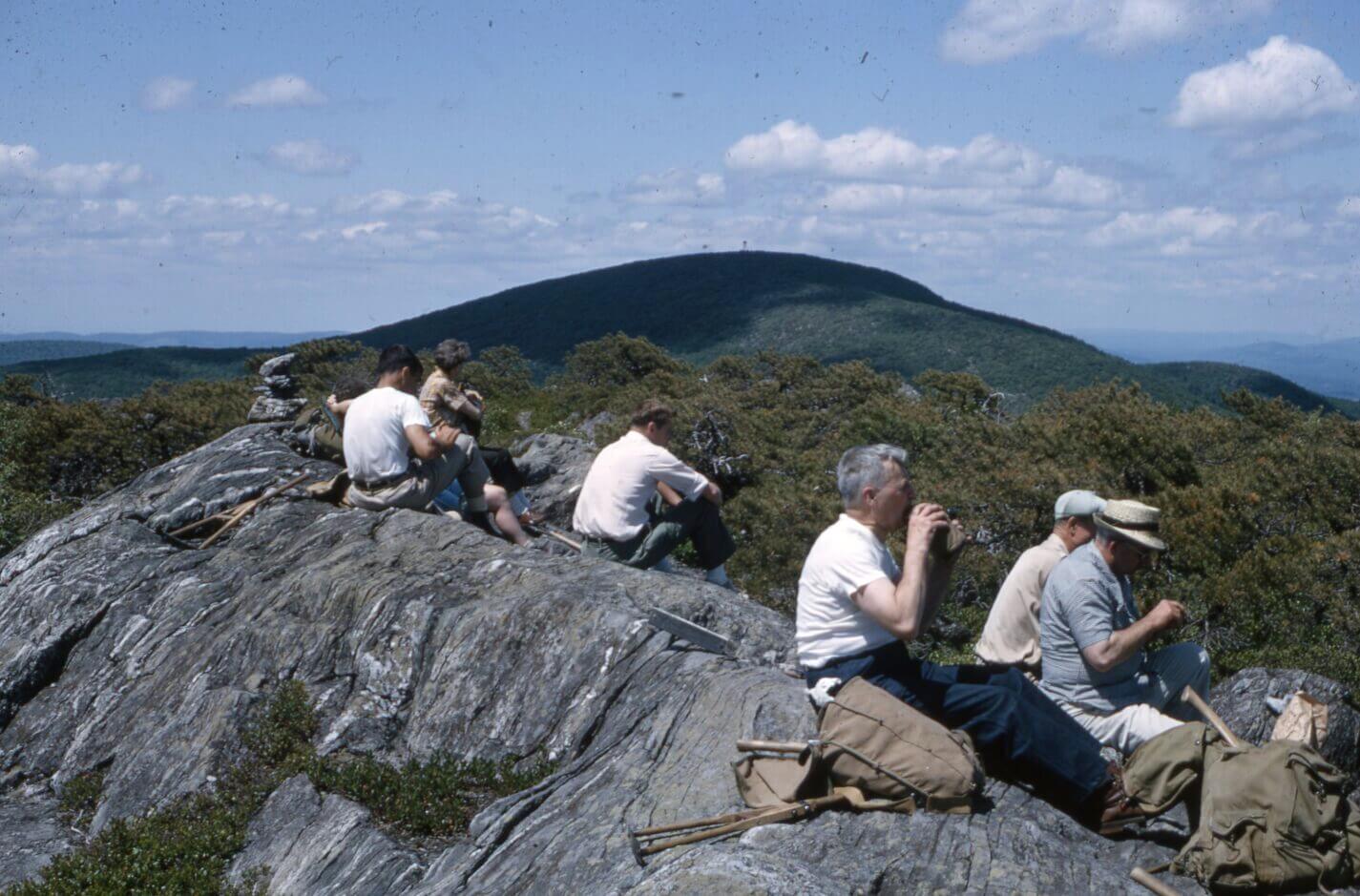

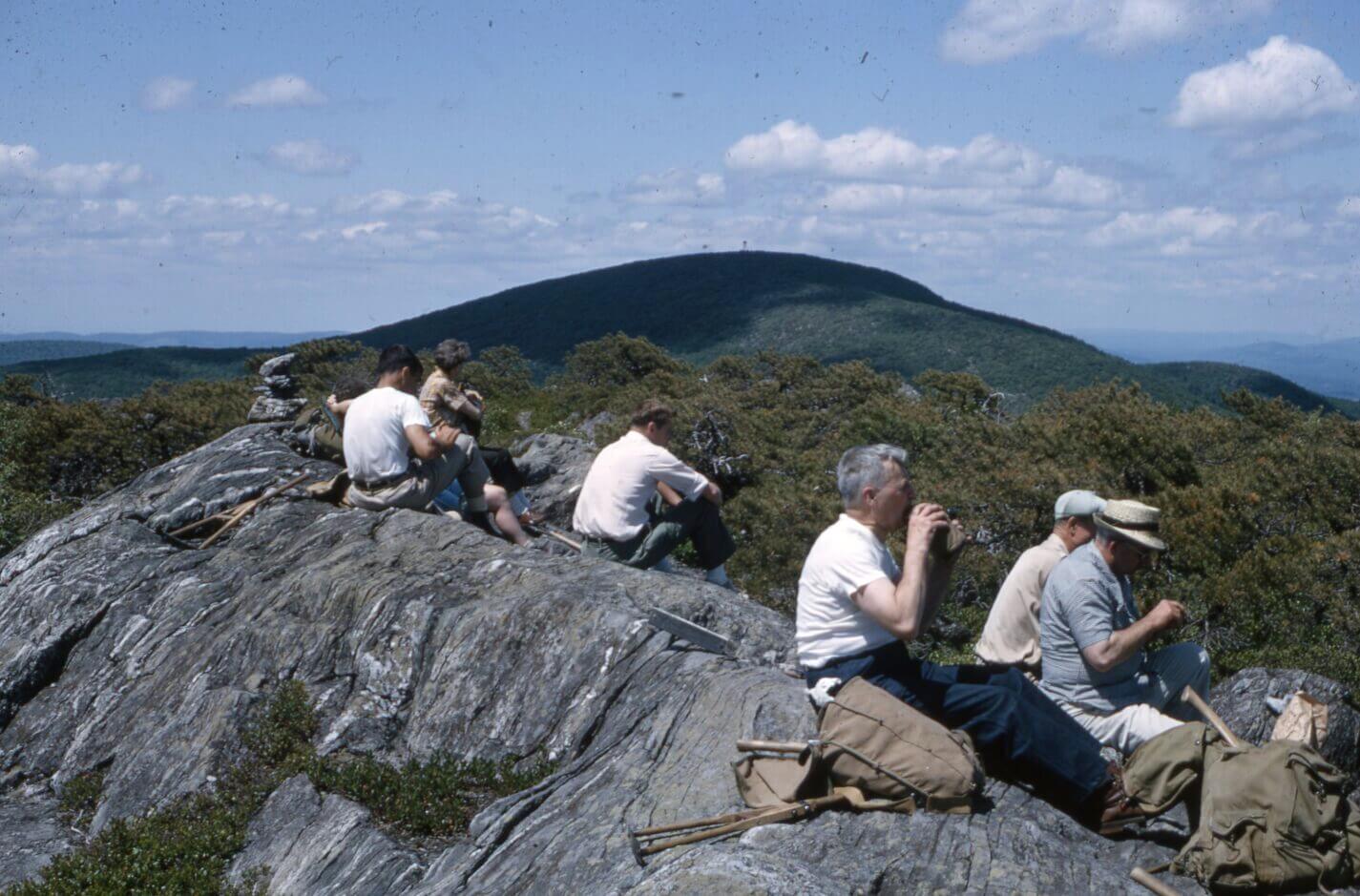

Hikers take a break at the summit of Mount Race on the Massachusetts A.T., with Mount Everett in the distance, in 1964.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

Bob Brown of the AMC Berkshire Chapter (now AMC Western Massachusetts Chapter) repairs a broken sign along the A.T. in Great Barrington, Mass., in 1987. AMC volunteer and professional trail crews maintain more than 275 miles of the A.T. in five states.

AMC LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

A.T. section and thru-hikers in New Jersey pass through AMC’s Mohican Outdoor Center, whose signs are shown here in 1999.

PAULA CHAMPAGNE

The A.T. is as popular as ever, with nearly 4,000 registered thru-hikers on the trail in 2021, according to the ATC. Hikers receive lodging, supplies, and other forms of support from businesses and residents of towns that border the trail. The Appalachian Trail’s creation is a testament to the vision cast in 1921 by Benton MacKaye and the dogged shepherding of early ATC leaders like Major William A. Welch, Judge Arthur Perkins, and Myron Avery. Its preservation and maintenance fall on a network of land conservation groups and outdoor clubs, which includes AMC. Ultimately, its continuation depends on all of us responsibly enjoying the trail—section by section or in a single season—and partnering with groups working to see its preservation for another century or more.