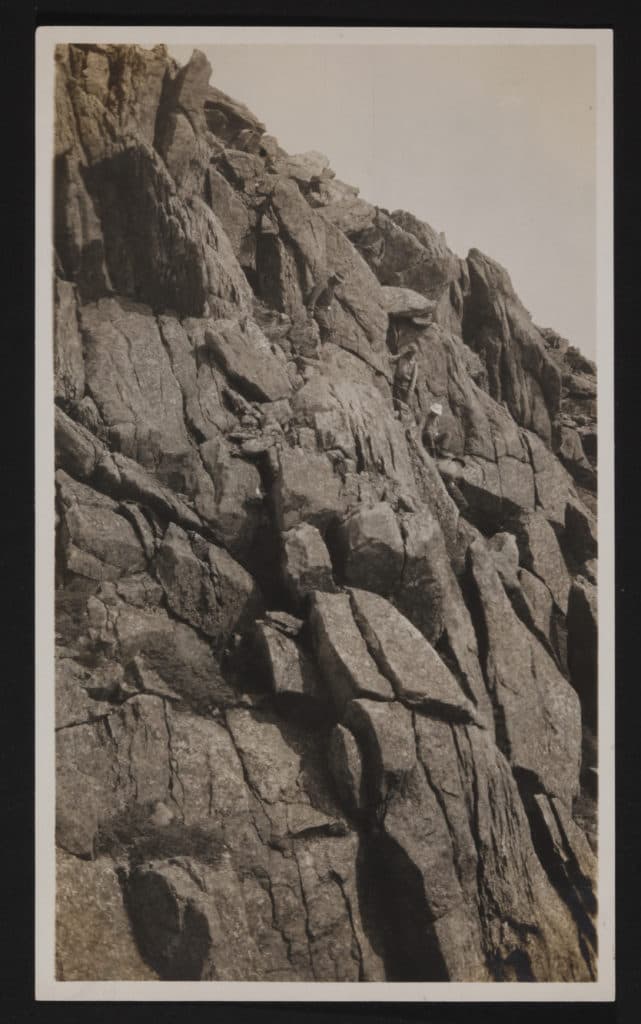

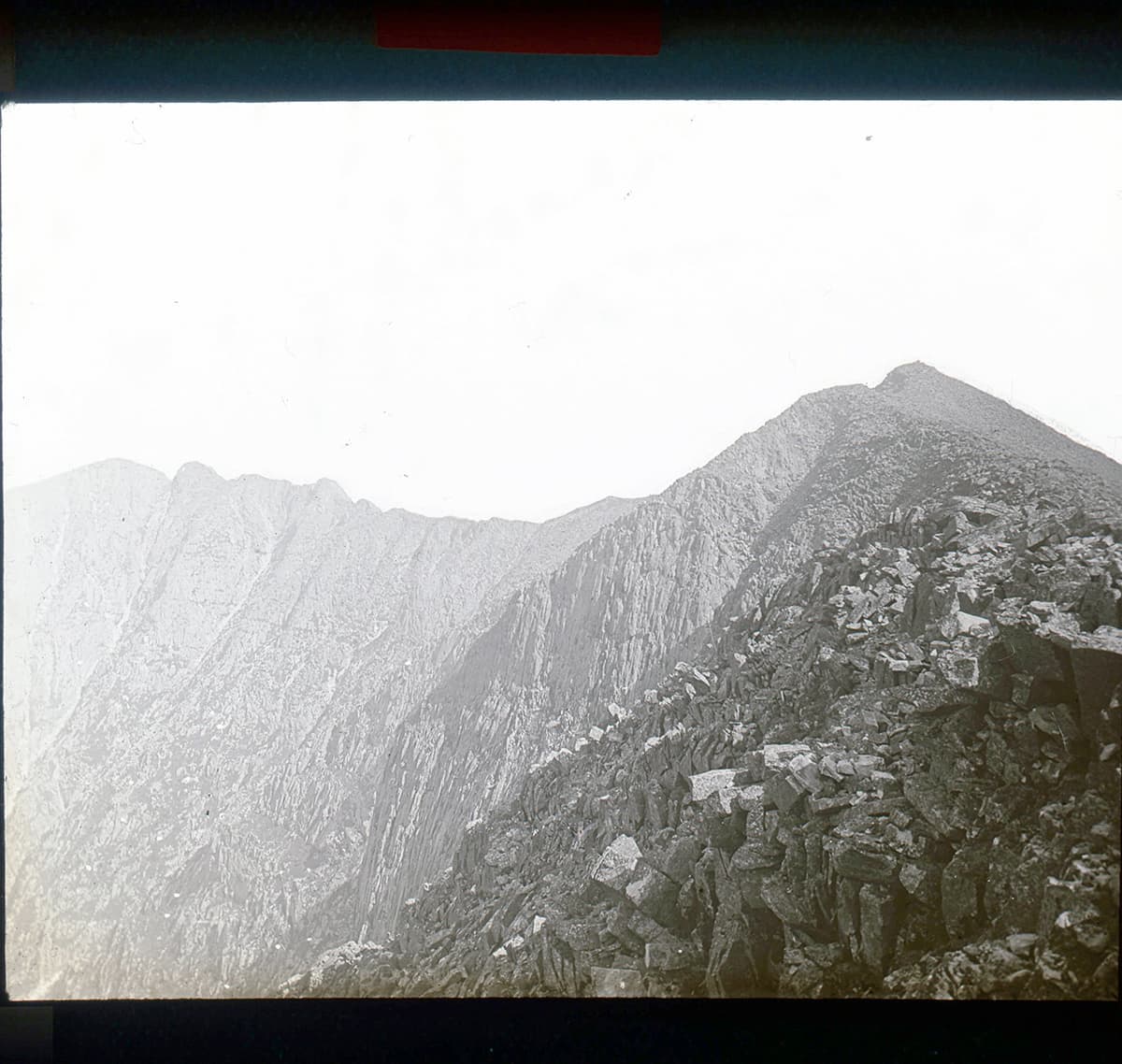

Katahdin is one of the most notable landmarks in the Northeast. As the centerpiece of Baxter State Park, the tallest mountain in Maine (reaching 5,269 feet in elevation), and the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail (A.T.), Katahdin attracts thousands of eager hikers each year. However, those who choose to summit Katahdin must use caution: it’s widely known as one of the most difficult peaks along the A.T.

Katahdin’s deeply rich history begins with the Penobscot Indians. The Penobscots, noting the incredible altitude of the mountain, named it “Katahdin,” which translates to “The Greatest Mountain.” For the Penobscot Tribe, the mountain represents the beginning of life, a place of birth and spiritual enlightenment. While the Penobscots made their living in the surrounding regions of the mountain, often hunting and fishing in harmony with the seasons, they cautioned against climbing to the summit. They believed that an evil spirit called Pamola resided there. Pamola, which translates to “he who curses the mountain,” is frequently depicted as a gigantic bird-like creature with the head of a moose and is associated with snow, cold weather, and storms. The Penobscots believed that if they summited Katahdin, they would either be killed or devoured by Pamola. So to appease him, they would offer him periodic sacrifices of oil and fat.

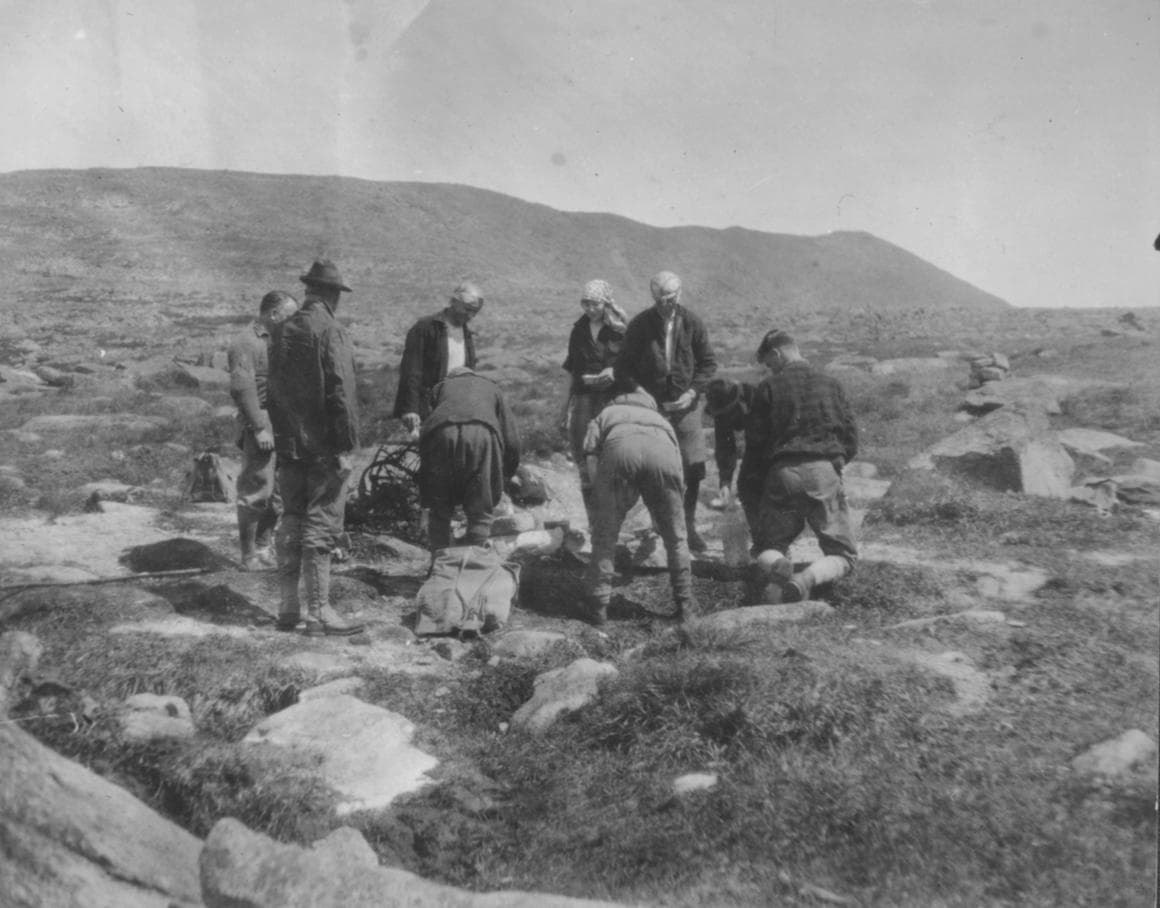

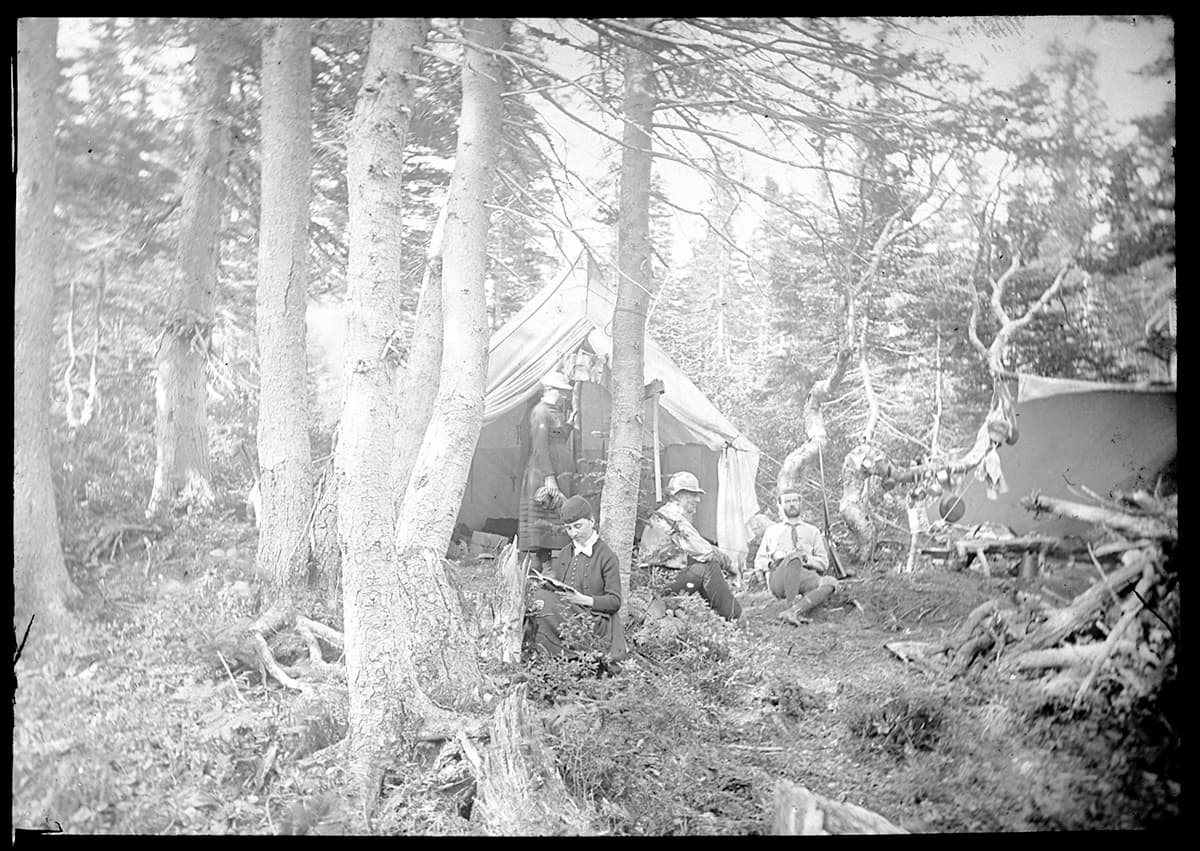

Undeterred by the beliefs of the Penobscots, many American and European surveyors who later arrived to the area had their eyes set on Katahdin’s summit. To non-Native American populations, little was known about the peak or its surrounding region. It wasn’t until the 1800s, when the Commonwealth of Massachusetts commissioned Charles Turner Jr. to conduct a survey of the northeast corner of the United States, that Katahdin came into focus. Turner hired two Native American guides to lead him and his group of ten men to the foot of the mountain. The guides, fearing the spirit of Pamola, refused to go all the way to the summit and issued several warnings to Turner. But Turner ignored them, and on August 13, 1804, he and his men made the first recorded non-Native American ascent of the mountain. Turner believed Katahdin to be so great that he thought it reached 13,000 feet in elevation.

Like Turner, author Henry David Thoreau, guided by a group of Penobscot Indians, attempted to summit Katahdin in 1846. Though he never actually reached the top, he helped to further popularize the mountain by recording his experience in a chapter of The Maine Woods.

The history of Katahdin dictates several essential lessons to its visitors. The beliefs of the Penobscots emphasize the importance of respecting the entire mountain—not just the summit—all of which is sacred land. And the popular tales of Pamola remind hikers to be cautious of fickle weather conditions and severe storms.Today, Pamola’s name is remembered on Pamola Peak, a summit on Katahdin, and the Penobscots continue to live on the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation in northern Maine. They frequently return to Katahdin for spiritual purposes.