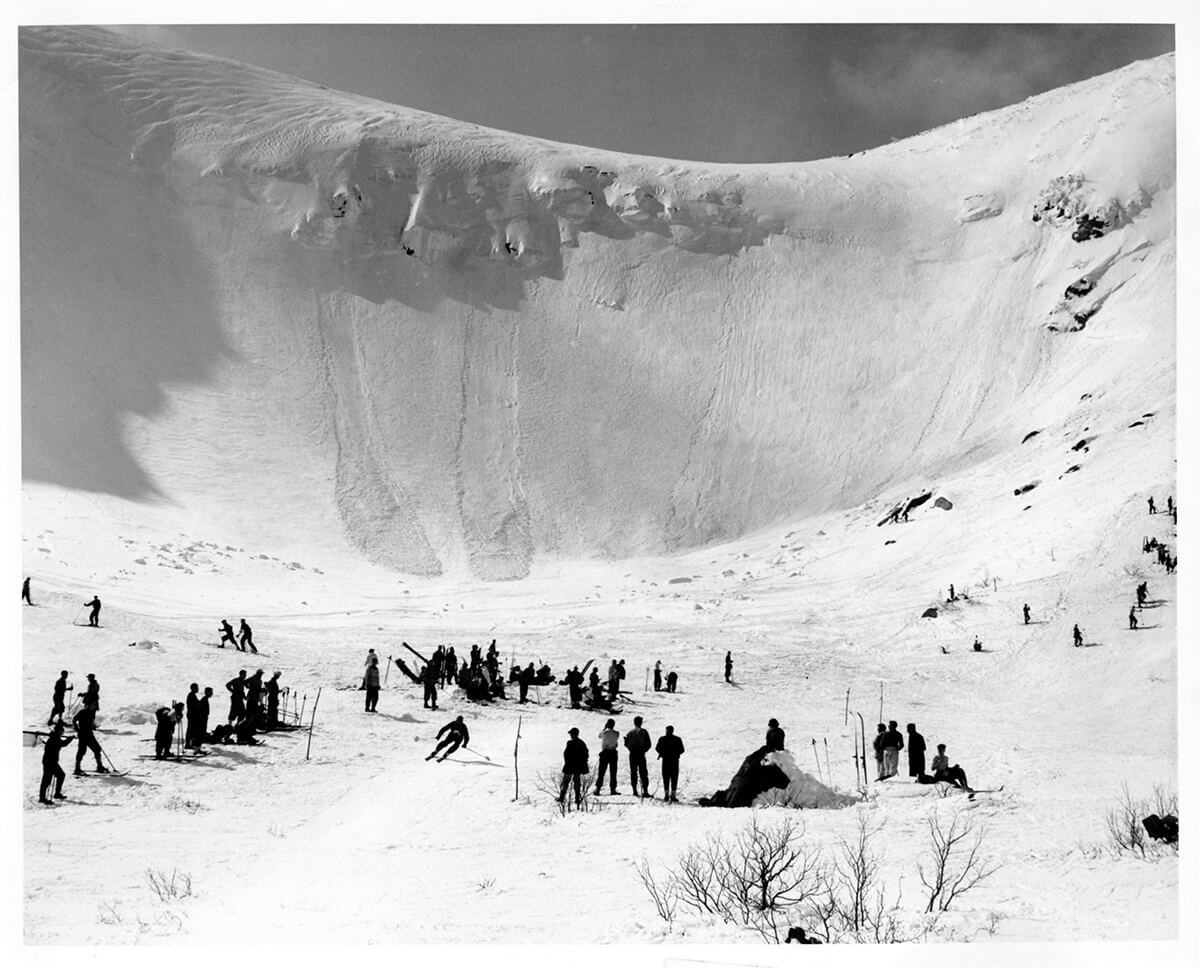

A group of backcountry hikers and skiers discuss avalanche safety in the shadow of a snowy Mount Washington.

Sarah Goodnow says she was lucky the first time she saw a natural avalanche. Lucky, as in she and others around her were in a safe place, allowing them to witness the phenomenon without fear.“It was after a snowstorm and there wasn’t much wind,” she recalls. “I could see Hillman’s Highway (a ski route on Tuckerman Ravine on Mount Washington) and the avalanche happened while I was standing on the cabin deck looking up. It was the luck of the draw that it happened while I was out there and had visibility.”

Goodnow has worked for AMC for six winters as the lead caretaker at Hermit Lake Shelter, a popular gathering point for backcountry skiers on their way to tackle the popular Tuckerman Ravine ski routes. Her caretaker role not only lets her cater to overnight guests and day visitors, but to also serve as a first responder to backcountry emergencies—anything from broken bones to lost hikers and skiers. In peak ski season—mid-winter to spring—this area sees its fair share of daredevils, injuries, and avalanches.

Frank Carus, lead snow ranger and director of the U.S. Forest Service’s Mount Washington Avalanche Center, says the White Mountains experience somewhere between 20 and 30 avalanche cycles—times when conditions are perfect to trigger avalanches—per year, depending on the length of winter and snow accumulation.

“Far more avalanches happen naturally than with a human trigger, fortunately,” Carus says. “Usually avalanches happen during or right after a storm, and we’ve documented a few cases of animals triggering one.”

Understanding what triggers an avalanche is just one component of preparing for a winter outing in the mountains, though. Experts like Carus, Goodnow, and Mike Brantina, a seasoned backcountry skier and avalanche awareness educator with AMC’s Boston Chapter, say that participating in an avalanche awareness class is an important first step to know the basics, but advise serious winter adventurers to take avalanche rescue classes for optimal preparation. These courses are designed to provide winter adventurers with the skills they need to be safe before heading out into avalanche territory.

“For any type of backcountry travel, either in the winter or summer, your mind is the first and best piece of equipment to have,” Brantina says. “This means starting your trip with a solid plan, communicating well with your group, observing your surroundings, and being willing to make changes to your plan as the conditions warrant.”

It’s important to recognize the signs of potential avalanches, the easiest being if there are signs of previous avalanches in the area.

Avalanche Types and Triggers

Avalanches need four things in order to occur: a slippery surface, which can include ice or melting snow; a weak layer of snow above that surface that could easily dislodge; a mass of snow that accumulates on that weak layer and can slide; and a steep enough slope angle, usually 30 degrees or more, says Brantina, who gets his instruction materials from Utah-based Know Before You Go.

Avalanches are not exclusive to ski slopes either. While one may picture images of massive snow shelves plummeting down a rocky cliff, the reality is that these deadly phenomena can occur anywhere, including below tree line, and are as much a hazard to hikers as skiers.

“The unwooded ravines and gullies in the White Mountains, particularly Tuckerman Ravine, Huntington Ravine, and Gulf of Slides, are some of the most recognizable avalanche terrain, but an avalanche can happen in any terrain where the four key ingredients are met,” Brantina says.

In order for a natural avalanche to occur, Carus says the terrain needs a foot or more of snow and strong enough wind speeds (which is any speed above 30 miles per hour.

“The wind breaks all the snow particles and create a tight snowpack,” Carus explains. “With some wind, this could trigger a slab avalanche either during or after a storm.”

Taken in 1937, this photo shows the paths of two recent avalanches in Tuckerman Ravine.

Slab avalanches are the most common and deadliest types that occur in the Northeast. When snow piles up over a number of consecutive storms, the upper layers melt in sunlight then refreeze, creating a heavy layer on top of lighter, looser snow. Eventually, the weight of these “slabs” reaches a point where the snow below can’t hold it anymore (and sometimes it’s just the addition of a few snowflakes that can push it over the edge), jarring it loose and sending it downhill as a cohesive chunk. Like a terrifying sled on a steep hill, a slab avalanche can reach speeds of more than 150 miles per hour. You can spot the remnants of slab avalanches easily by the crisp shelves of snow indicating where the snow gave in.

Loose snow avalanches, on the other hand, are triggered by warming conditions or an object falling or person stepping onto the accumulated snow. These avalanches tend to be less deadly (but still serious), as the snow breaks below the skier or hiker that sets it off.

Matthew Schraut, co-instructor for AMC New Hampshire’s ski committee avalanche course, demonstrates how a beacon works.

Preventable Dangers

Ninety percent of avalanches when a human is caught are triggered by someone in that person’s group, Brantina says, citing Know Before You Go data. In front country ski resorts, the risk is mitigated by staff, who each morning head out to the slopes to measure snowpack; if they determine there is a risk for avalanches, they will trigger one on purpose using explosives. In the backcountry, though, when access to a ski slope is by foot or ski only, it’s up to the adventurer to do what they can to prevent disaster.

Each winter, AMC chapter ski committees organize a variety of lectures and workshops to ensure skiers, winter hikers, and other outdoor enthusiasts know what to look for when out in avalanche-prone areas. While Brantina’s lectures give an overview, the AMC New Hampshire Chapter ski committee hosts an annual two-day workshop at Pinkham Notch Visitor Center that provides attendees with hands-on practice learning how to rescue someone who might be trapped. (Due to COVID-19 restrictions, this class is canceled for early 2021, but alternative courses and guided adventures are available through AMC.)

“Poor decisions are made because of ego, exhaustion, lack of experience, peer pressure, ignoring or unaware of evidence. Our course introduces people to general principles of avalanches and how to avoid them, what the red flags are, and how to react. It’s a lot of situational awareness,” explains Casy Calver, a ski leader and avalanche awareness instructor in the AMC New Hampshire Chapter ski committee.

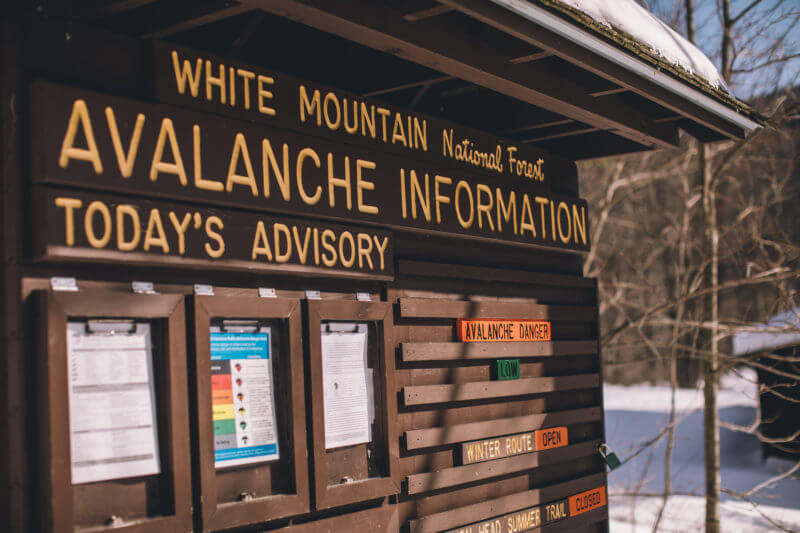

This kiosk outside Pinkham Notch Visitor Center provides adventurers with daily updates on weather reports and avalanche conditions before they hit the trails.

Avalanche Awareness

Someone venturing into the snowy backcountry needs to know the signs of potential avalanche. An easy-to-spot sign is evidence of previous avalanches: cracks in the snow, jagged shelves where slabs may have broken off, big piles of snow at the end of slopes, or snaped or bent trees and branches, Brantina says.

“Sometimes you may hear a ‘whoomphing’ sound as the snowpack collapses,” Brantina adds. “New snow and blowing or drifting snow are two other signs, with a rapid rise in temperature being another.”

As you travel, keep in mind how the snowpack moves; if it seems loose, you may encounter similar conditions higher up. On steeper slopes, try to travel at the highest point and don’t linger for too long—a quick slip could be catastrophic for you and your group. Be sure to check the conditions report before you head out, too.

The Mount Washington Avalanche Center issues a daily avalanche report at 7 a.m., which includes a “Danger Level” based on the likelihood, size, and distribution of avalanches. Using data gathered by volunteers at the U.S. Forest Service, AMC, Mount Washington Observatory, and volunteers, officials can estimate an avalanche forecast with five levels ranging from “Low” to “Extreme.”

“It’s helpful because it provides a base level of information for people to make decisions,” Carus says.

This scale is determined by the daily conditions the region faces. Is the wind strong? Was there recently a snowstorm that could add to the snowpack? What is the current measurement of snowpack? Are temperatures rising, causing snow and ice to melt? With even one of these factors in play, you could likely experience an avalanche on your outing, and would need to determine if it’s safe to head out. For instance, “if people wait just 24 to 48 hours to venture out after a snowstorm, we could eliminate 90 percent of avalanche accidents,” Carus says.

With a beacon buried in the snow, participants in AMC New Hampshire’s avalanche course practice techniques to dig someone out if they are buried in an avalanche.

Avalanches Essentials

Probably the most important piece of gear for anyone heading out into the snowy mountains is an avalanche beacon—a device that helps find someone buried (or lost) in the snow—says Martin Janoscheck, co-instructor for AMC New Hampshire Chapter’s avalanche safety course. Usually attached to a harness under your layers, the beacon sends a signal to rescuers identifying your whereabouts. Just be sure to turn it on as soon as you hit the trail.

“We say that you keep your beacon on from car to bar,” Janoscheck says. That way, rescuers can find you even if you run into trouble close to the trailhead.

How these devices work is that the beacon has two modes: one that emits a signal, and a second, the transceiver mode, which picks up that signal to help locate someone buried under the avalanche. All you need to do, as the rescuer, is switch the mode of your beacon to start your search.

Martin Janoscheck, co-instructor for AMC New Hampshire Chapter’s avalanche safety course, shows the group an avalanche saw, used in cases when snow is tough to break through after an avalanche.

Other items you should pack when heading out into avalanche country include a shovel, which will aid in digging out someone from the snow; a snow saw, for denser snowpacks; an inclinometer to measure slopes; an avalanche probe; and the 10 essentials. Optional accessories include an Avalung, a device specially designed to extend the lifespan of your oxygen levels when buried; avalanche airbag, which you would inflate as the avalanche hits you to help keep you on top of the snow; a reflector; and, of course, the knowledge on how to use these tools.

According to Matthew Schraut, co-instructor for AMC New Hampshire’s avalanche safety course, the leading cause of death from avalanches is asphyxiation, as carbon dioxide builds up under the snow as the victim breathes.

“As you breathe more, carbon dioxide builds up and the snow around you melts, creating essentially a ‘death mask,’” says Schraut. The Avalung is designed to divert the carbon dioxide away from your face, giving you up to an hour of added breathing time while you wait for rescue.

Tuckerman Ravine, a steep bowl formation below the summit, is a bucket list adventure for backcountry skiers, but also known for its deadly avalanches.

If you experience an avalanche…

Get out of the way. That’s easier said than done, of course, but it’s the best chance for survival. Avalanches move fast—reaching 80 miles per hour in less than five seconds and quickly increasing to more than 200 miles per hour—so if you are on skis, try to maneuver to the right or left of the avalanche path. If you can spot it far enough ahead, ditch your skis and poles, but keep your pack on, for buoyancy.

AMC’s Essential Guide to Winter Recreation provides more details on avalanche safety, with a heavy emphasis on traveling with groups in avalanche country. In the case of an avalanche, you’ll want to be sure to shout to others in your party, so they can get out of the way and know where you are, in case you are buried.

If you can’t escape an oncoming avalanche, treat its impact the same way you would jumping into the water: turn your back to it, crouch down into a ball, and take a deep breath. Once in the avalanche, kick your legs and move your arms—again, like swimming—to try to stay as close to the surface. The snow will likely disorient you, so if you are conscious and sense the snow has slowed, try to wriggle around to create an air pocket around your face, and if possible, try to dig yourself out. If you are unsure of which way is up or down, spit—gravity will indicate where the ground is. And remember, if your beacon is on, rescuers will be able to find you more quickly.

Participants in AMC New Hampshire’s avalanche class practice using a probe to find someone buried by an avalanche.

Search and Rescue

If you or someone in your group is buried by an avalanche, it’s important to act quickly—there’s not enough time to run for help. According to Brantina, the average person has a 90 percent survival rate if they can dig out within 10 minutes after being buried by an avalanche. That survival rate drops precipitously thereafter: 36 percent if you are buried for 11 to 20 minutes; and 24 percent or less if buried for more than 20 minutes.

In the front country, you’ll sometimes see a line of rescuers descending the mountain after an avalanche to rescue trapped skiers, but in the backcountry, you take on the role of rescuer, working with the other unharmed members of your group to save distressed hikers and skiers.

Step one is to assess that the area is safe before heading toward the spot you last saw your fellow adventurer, says Schraut and Janoscheck. In some cases, if you are lucky, the person isn’t fully buried, making it easier to find them.

Switch your beacon into the transceiver or “search” mode, which will pick up the signals of any beacons in the area, notify you of how many there are, what direction to head to reach them, and how far away each one is, approximately. Follow the transceiver toward the assumed buried person; as you get closer, the beeping of your device will get louder and more frequent.

Once you locate your spot, you’ll need to mark the area with an ‘X’ in the snow, then use a probe—a brightly colored collapsible pole, similar to tent pole—to gently poke the snow. Keep poking the area until you think you’ve located the person, then carefully start digging using your shovel or snow saw.

“When digging out, it’s important to get their head out first,” Schraut says, alluding back to the “death mask” scenario.

Risk and Reward

Even with all this risk, outdoor enthusiasts shouldn’t be deterred from heading out this winter. With proper training, research, and preparation ahead of your trip, you can enjoy all the splendor that winter in the East has to offer. AMC offers a variety of resources to get you started—just check AMC’s Activity Database for upcoming virtual lectures on avalanches and future trainings in 2021.

And remember, if you’re unsure if it’s safe to head out, save the adventure for another day.