Chuck Hutchins at the summit of Mount Madison, the final peak in his effort to hike all 48 New Hampshire 4000 footers while in his 80s.

Everyone has their own story about why they hike the rooted, rocky trails of New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest. My father, Chuck Hutchins of Canaan., N.H., has hiked here for more than 50 years. This is his story.

He began in 1970 with a family hike up Mount Willard. Six adults and 12 children in sneakers and sweatshirts and packing peanut butter sandwiches on white bread easily hiked to that amazing view. Dad’s first 4000-footer, with the same crew, was Mount Lafayette in 1971. He and my mother, Fran, loved it. Not everyone else was as enthusiastic. Some never hiked again. My younger sister Tish and I, to my regret but not hers, were two of the dropouts. My brothers, Charlie and Chris, completed their 48 New Hampshire 4000 footers along with my parents in 1975.

One of my dad’s lists was the highest 100 peaks in New England, known as the NE100. Many of these hikes involve bushwhacking. Never having bushwhacked before, Dad wisely attended an AMC map and compass course taught by Doug Hunt and Dave Langley. There he met Fred Shirley, and they pursued the NE100 together. My father enjoyed the mental challenge of charting a trail through the undergrowth. When I asked him if he had any amusing experiences to share about his map and compass expeditions, he replied, “No, bushwhacking is pretty serious business.” They completed this list in 2005 with grit and determination—but no levity, apparently.

Then my father joined AMC guide Carl Rosenthal’s Wednesday hiking group. They hiked year-round and encouraged Dad to try winter hiking. He was not interested. My father does not like the cold. He wears a knitted hat inside the house in winter. But the group’s enthusiasm, and Dad’s desire for a new challenge, led him to try. “Once I started hiking in winter, it became my favorite season,” he tells me. “No mud, no bugs, and the walking is easier on the snowshoe-packed trails, above the roots and rocks.”

One day while tallying his hikes, Dad realized that he had climbed all the 4000 footers in his 70s except for three peaks. In October 2010, he and the Wednesday group summited his last peak, Mount Pierce. In celebration, Dick Widhu created a patch depicting a hiker with a walker, which read “48 over 70.” More than 75 people have claimed this patch, including dad.

***

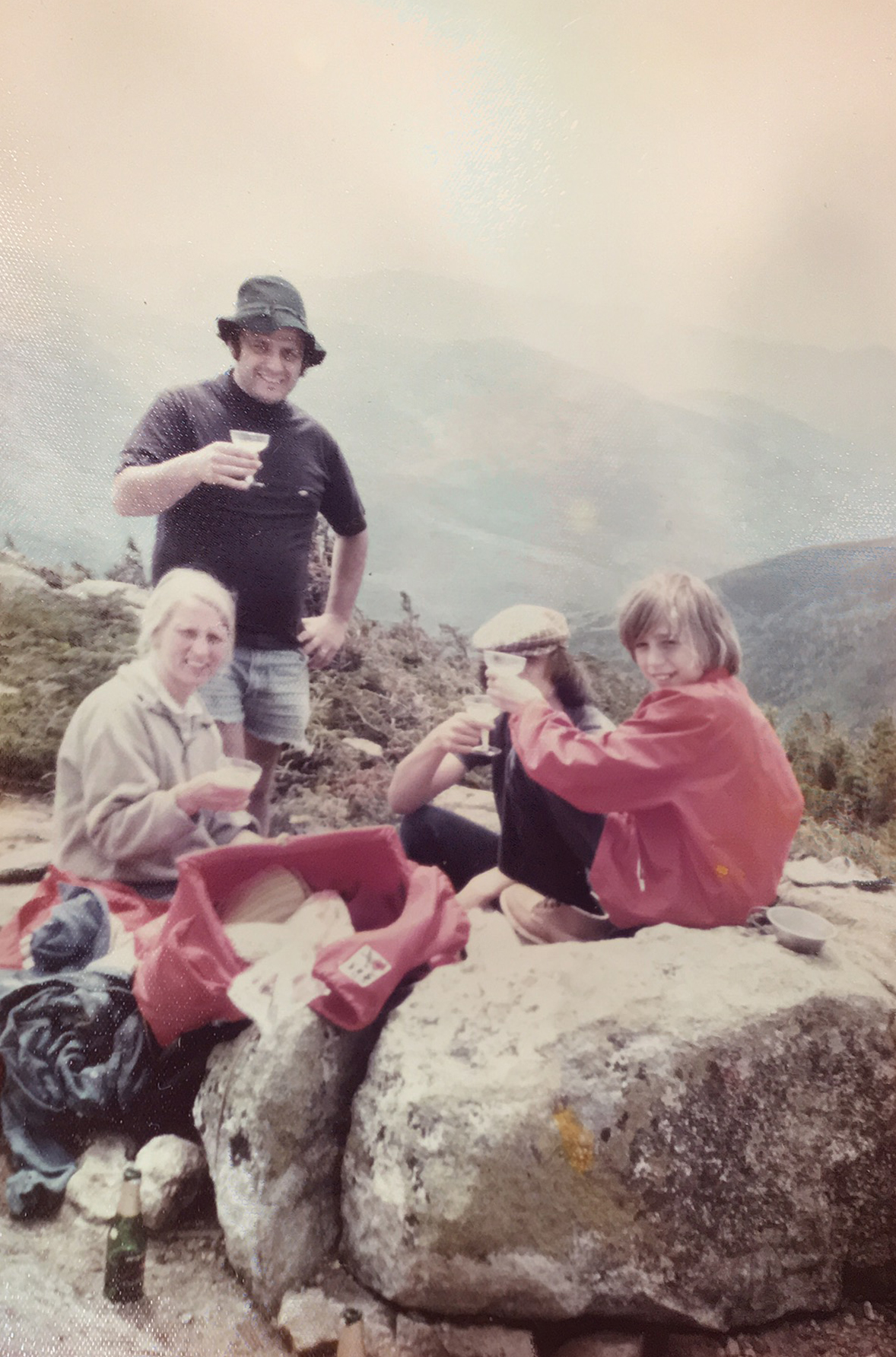

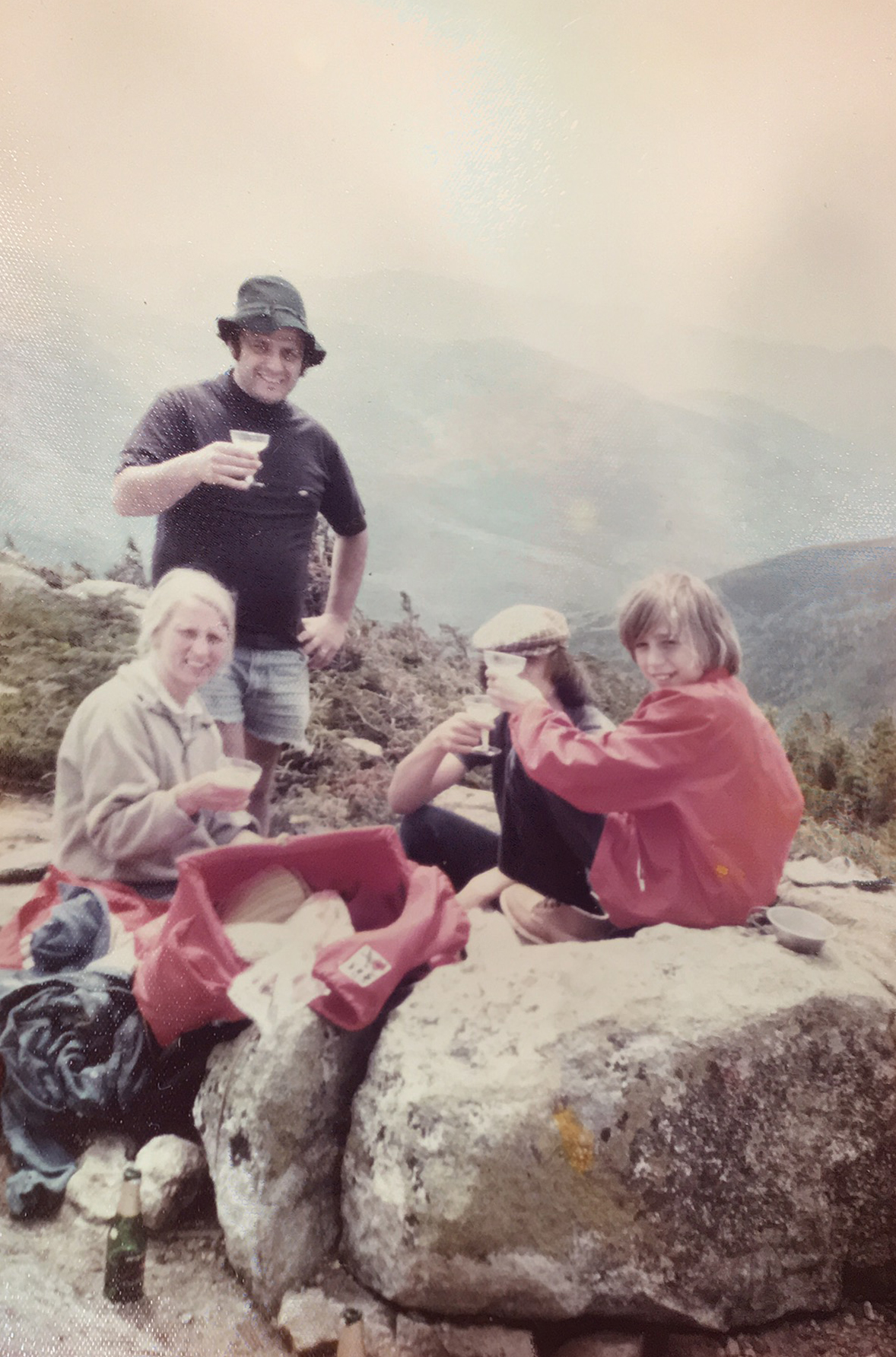

Fran and Chuck Hutchins with their sons after joining the 4000 Footer Club in 1975.

At 79, Dad quit hiking when my mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer. The challenge and beauty of the White Mountains were no match for his desire to spend every moment with his wife of 60 years. His new list was to make more memories with her. That last bittersweet summer, Mum’s children and grandchildren visited often. At each reluctant good-bye we hugged her small body and touched her soft cheek. It was impossible to believe she was leaving, but equally impossible to stop her going. When she died in 2019, Dad was bereft, alone for the first time in his 81 years. “It’s not living alone that’s hard,” he says, “it’s living without her.”

After her death, Dad struggled to find purpose. He decided to start walking again, something he’d abandoned when my mother was sick. New Year’s Day 2020, Dad walked to the dam at the end of the road and back, about 2.5 miles. He wasn’t fast, but he did that walk every day. In the gray, the wind, the cold, and the snow. By the middle of January, he was walking five flat miles a day. He added hills. He lost weight and grew stronger. He announced that he was going to try to hike all 48 4000 footers in his 80s.

First, he hiked South Moose Mountain with his son Chris and daughter-in-law Doreen. He gave himself a 10 percent chance of achieving his goal of hiking all 48. Next, he successfully hiked Mounts Roberts and Major with me and my husband Joe. Now he calculated a 50 percent chance he could summit above 4000 feet. He wanted the high peaks because, as he puts it, “they give me a sense of purpose. I really enjoy being above tree line for the view. The lower peaks don’t give you that sense of place. On the lower peaks you could be anywhere. On the high peaks you know exactly where you are in the mountains.”

Then, in March 2020, COVID-19 pandemic, and the subsequent lockdowns, began. White Mountain National Forest closed. Careful review of the restrictions revealed that only the parking lots were closed. My father lives about 1.5 miles from the Appalachian Trail. He could walk to the trailhead and legally hike the A.T. Training for the high peaks resumed. By the time the lots re-opened, he would be ready.

Dad and Chris hiked the first 4000 footer, Mount Moosilauke, in May 2020. He now gave himself a 70 percent chance of achieving his goal. They planned to hike a 4000 footer once a week, mid-week, to avoid the crowded weekend trails. They physically distanced and masked when they saw another hiker. If the peak was occupied, they ate their lunch elsewhere.

On his third hike, Cannon Mountain, Dad was exhausted and hurting. He remembers collapsing onto a rock, head in his tired hands, asking himself, “What am I doing here. Am I stupid? Am I crazy?” For a few days, my dad considered quitting. After consulting with family, he tried resting the day before a hike and increasing his calories day-of, which was successful. He now rated his chances as better than 80 percent. He continued knocking off peaks.

***

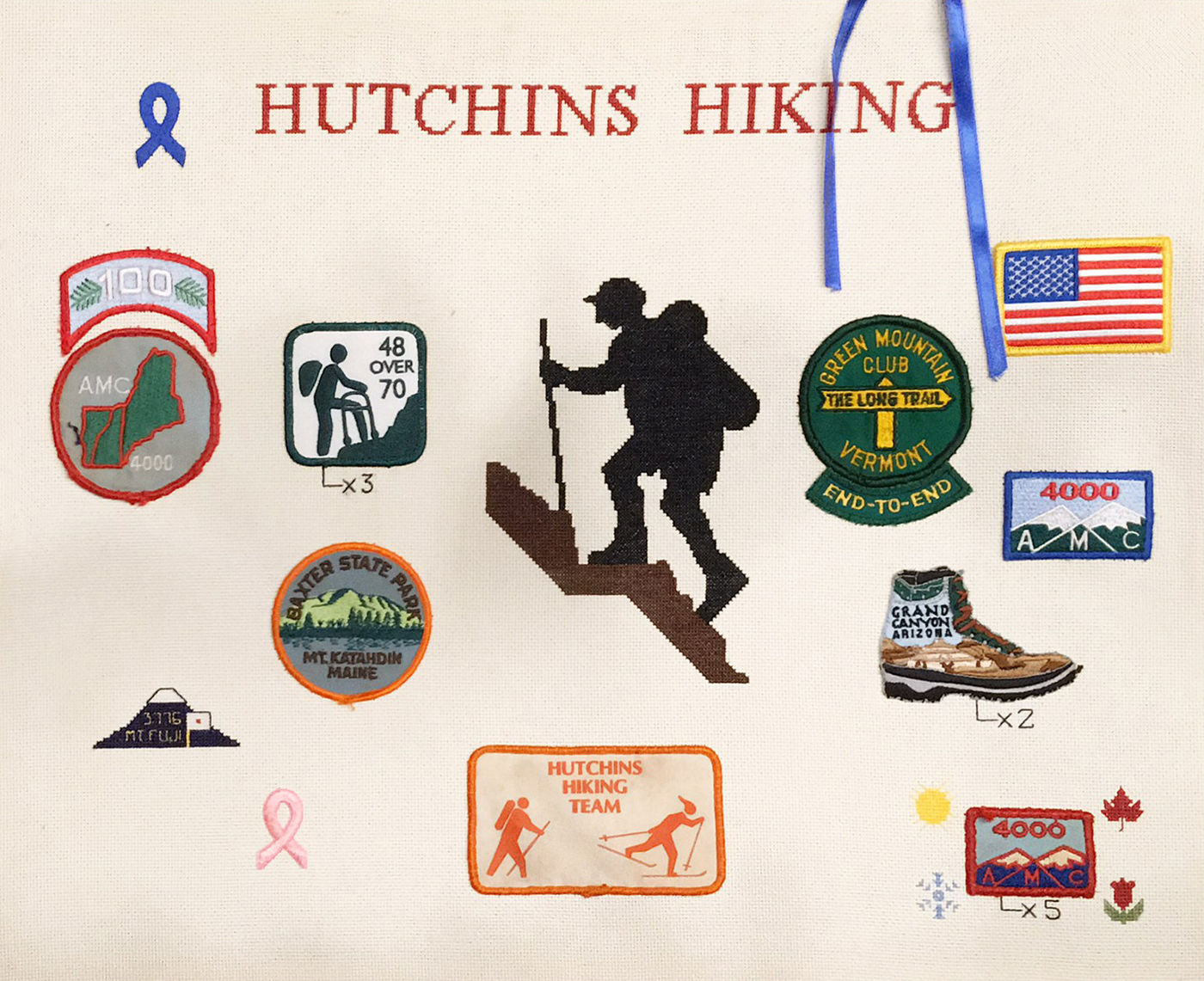

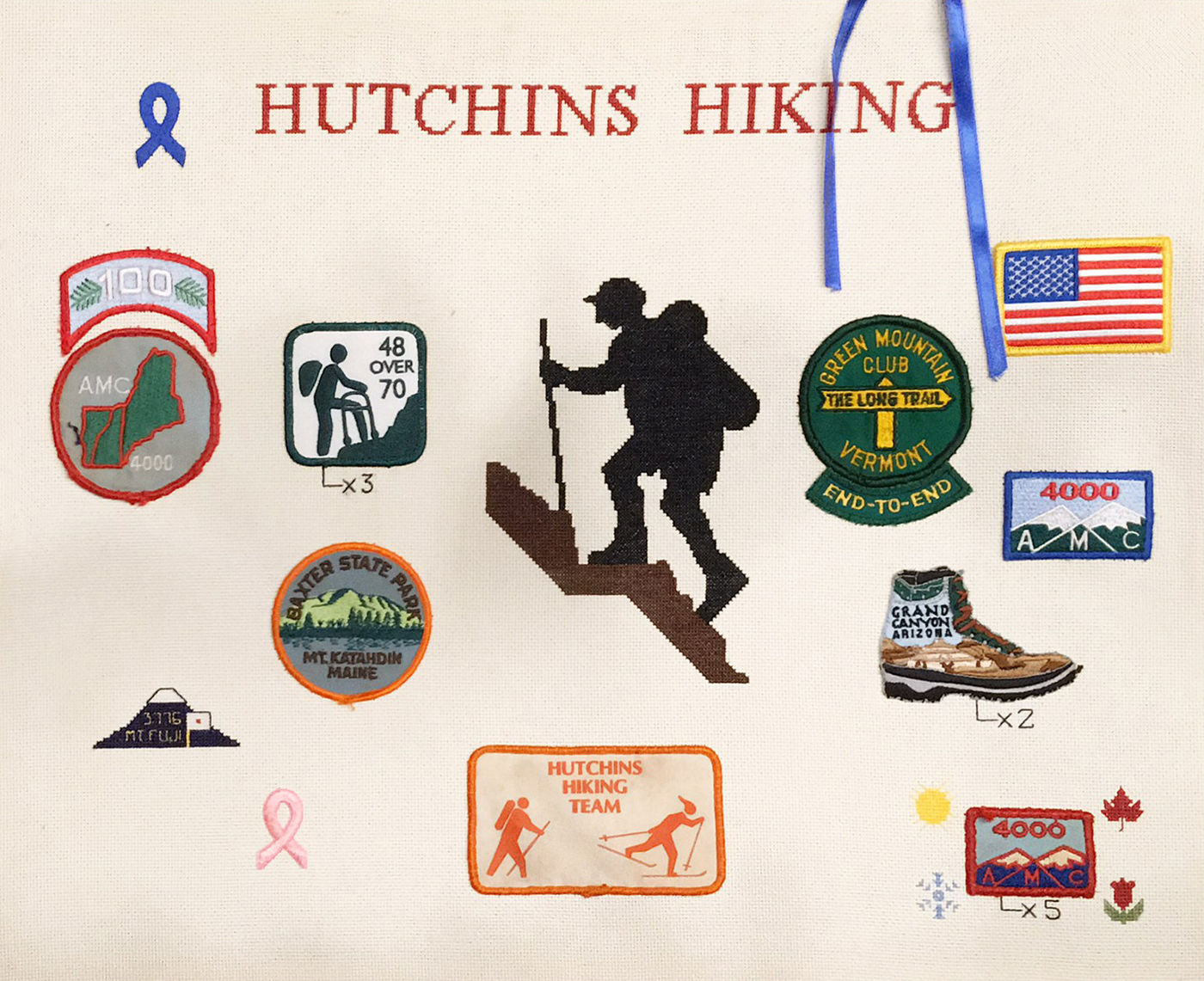

A hand-made display of Chuck Hutchins’ hiking patches, which he cross-stitched and sewed himself. Hutchins has completed the 48 New Hampshire 4000 Footers six times, including three times in his 70s and once in his 80s. The blue ribbons are in memory of his wife, Fran, who passed away in 2019.

The Caps Ridge Trail on Mount Jefferson is renowned for its breathtaking views. It demands a lot of boulder scrambling. My father likens it to doing 100 burpees while climbing. He and Chris summitted Mount Jefferson two hours behind schedule, and then turned up trail toward Mount Adams. After 100 slow feet, Chris decided to abort the hike because my father was spent. After that hike, my father rated his chances of bagging all 48 at zero. He was done. It was too much. He was too old. He had hiked Jefferson, Adams, and Monroe together a few years earlier and remembered it only for the spectacular ridge walk. This time he crawled over the boulders on his hands and knees, something he had never seen anyone else do.

Still, an ember of dad’s dream still glowed, and after a time of rest and several pep talks, he was back on the trail with an uneventful hike up Mounts Wiley, Tom, and Field. He ticked off a few more peaks accompanied by two hiking friends, Sue Rose and Gerry Coutu.

In February, Dad and I hiked Mount Jackson. About a mile up, I remembered my father’s contention that hiking on the snow-packed trails was easier than on the rocky, rooted trails. It was not. He was right about the beauty of winter hiking though. The snowfall was transformed by wind and change into frozen topiaries of camel, stegosaurus, and turtle. In places, 5 feet or more of snow lay undisturbed along the tree limbs, arching across the trail, a snowy cathedral with ceiling fallen away to a pure blue sky. Finally, gloriously, just as I was contemplating defeat, we summited to a fairyland panorama, snow and hoarfrost dazzling on every peak for hundreds of miles. By trail’s end, I was exhausted. As my sister Tish says, “It isn’t easy keeping up with an 82-year-old dynamo.”

My father and Gerry were determined to hike Mount Isolation before spring using a winter bushwhack that cuts out 2 miles. When they met other hikers on the trail, Gerry joked, “We have to keep moving, because if we are late, the nursing home won’t save us any dinner.”

In June, my father attempted a solo summit of Mounts Adams and Madison. A quarter of a mile from Adams’ summit, the winds were so strong that he hunched over his poles to brace himself from blowing over. Two descending hikers reported the wind was so powerful they crawled to the summit. He reluctantly turned back again.

On July 11, 2021, my father and Sue booked a night at AMC’s Madison Spring Hut. The forecast called for calm and no rain. At 3 p.m., the two summited Mount Adams. At 5 p.m., my father was atop Mount Madison holding a sign that read “48 over 80.” What began in a lonely, gray winter’s grief ended in triumph on the final 4000 footer—one of the more difficult hikes, no less. Back at the hut, the croo, who my father says were supportive throughout, celebrated his feat with the other guests.

Dad came off the mountain talking about a group of men at the hut whose friend was diagnosed with cancer a year earlier. They made plans to hike the Presidential Range when he recovered, but he died two weeks before their hike. Still raw with his loss, they hiked in his memory. I asked my father, who turned 83 a few weeks after finishing, if he was hanging up his boots.

“Nope,” he said. “I need purpose. I can’t just do puzzles and watch TV. This helped me through a difficult time. I credit Chris with helping me get here. I need two hikes to finish the New England 4000 footers again, there’s the 52 With A View, and the fire towers with your sister…”

Every hiker has their own story. This is my father’s.