From Boy Scout camp in the 1950s (center) to solo backpacking in the Yukon (bottom right) to local hikes in New Jersey (left), J.R. Harris has always blazed his own trail.

As J.R. Harris likes to tell it today, the first time he saw grass, he tried to smoke it.

He’s joking, of course, but the rib illustrates how shocking an introduction to the backcountry can be for a 14-year-old city kid. Climbing off the bus at Ten Mile River Scout Camps in Narrowsburg, N.Y., Harris describes feeling like he was a million light years away from home—in reality, a distance of just 130 miles. In an instant, the familiar sea of New York’s steel and pavement had been replaced by the mighty Catskill Mountains’ never-ending ocean of giant beech, maple, and oak trees.

“I got off the bus, looked around, and I was on a different planet,” Harris, 75, recalls today.

That was more than six decades ago. Summers at Boy Scout camp not only shaped the young life of the African American teenager from Queens; they set the stage for a lifetime of outdoor exploration. In addition to hiking all over the United States, Harris has circled the globe 13 times, at least, chasing multiweek backpacking treks in some of the most unspoiled locations on Earth: the remote Adirondacks; Alaska’s Yukon; Greenland; the Arctic Circle; the Amazon; the Andes; Tanzania; and Tasmania (three times), to name a few. When he visits a place, he embeds with the local indigenous tribe or village, studying the culture and pitching in where he can. In 1993, Harris was voted into the Explorers Club, the fabled Manhattan adventure society whose membership includes pretty much every globetrotter of note between Mars and the Mariana Trench.

He has completed nearly all of his trips solo while raising two children as a single parent and growing a successful consulting firm that caters to many top international brands and powerful governments. He has counted Jerry Garcia and the Dalai Lama among his friends. Hearing Harris describe his journey from Queens to the farthest reaches of the natural world, one can’t help but wonder: How has he managed to pull it all off?

J.R. Harris inside the fabled Explorers Club in New York’s Upper East Side, where he’s been a member for decades.

On a sunny spring morning, I find James Robert Harris waiting in the parlor of the Explorers Club headquarters, an exquisite 1910 stone and brick townhouse on New York’s Upper East Side. Wearing khaki hiking pants and a bright red shirt, Harris blends into the red leather armchair in which he’s sitting, reading a book. He’s lanky and fit, with a big smile and a stud earring in one ear. Even with the flecks of white in his goatee, Harris looks considerably younger than his 75 years. Behind him, an ornate fireplace and mantle is flanked by two early 20th century elephant tusks—vestiges of a less ecologically mindful era of exploration.

“So, you grew up around here?” I ask.

“Well, not around here!” Harris replies, with a laugh, his eyes darting to the dark wood molding lining the ceiling and the priceless artifacts hanging on the walls. He seems to recognize just how far he is, culturally and socioeconomically, from where he was raised: Pomonok Houses, a hulking New York City Housing Authority complex, 10 miles to the east.

He still lives in Queens, though, in a rent-controlled apartment, where he has been for decades. After all, Queens is where a young J.R. played basketball and stickball with the neighborhood kids, darted in and out of busy streets, and greeted his father when the elder Harris returned from long shifts waiting tables on a train’s dining car or, later, driving a truck for the United States Postal Service. Queens is also where J.R. got lost in the stories of explorers and adventurers: Lewis and Clark, Buffalo Soldiers, Davy Crockett, Kit Carson. He dreamed of joining them one day.

“Everybody said, ‘You can’t be an explorer,’ ” Harris remembers. “ ‘You’ve got to have money to be an explorer. You’ve got to be white.’”

When summer heat sparked violence in the neighborhood, Queens is also where his parents put him in the Boy Scouts. He hated it at first and was teased by his friends when he donned his uniform. Then, in 1958, he boarded a bus to camp in the Catskills, and everything changed.

At camp, Harris learned how to keep a fire lit in the driving rain, track animals, and tie knots. For eight weeks each summer, the teenager breathed deeply from the mountains, slurping up every experience and skill and filing them away to access later. The mountains began to change him—one of the only people of color at the camp. But while Harris was away, preparing to follow in the footsteps of James Beckwourth and Edmund Hillary, many of his friends were running around with street gangs, experimenting with drugs, and committing petty crimes.

“A lot of them just didn’t have any sense of what they wanted to do in the future; they were kind of living day-to-day,” Harris recalls. “I had more of a vision that there was stuff out there that I wanted to see, that I wanted to do.”

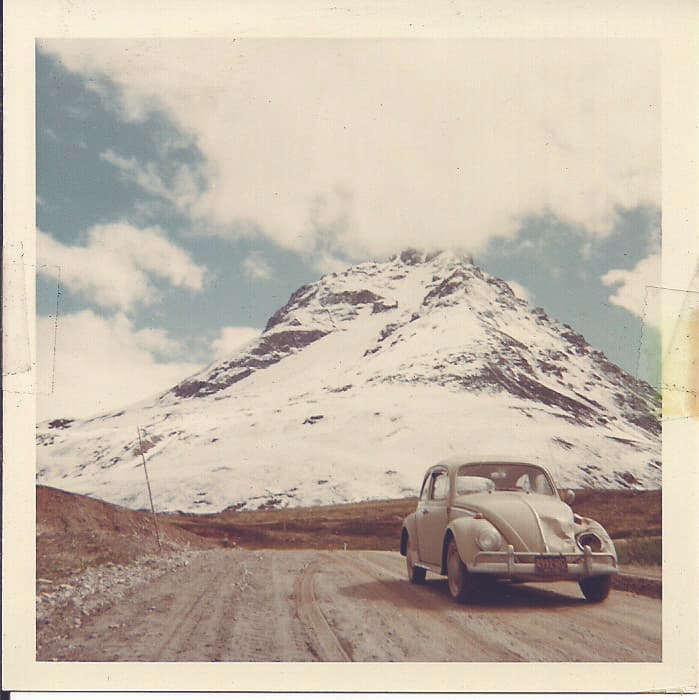

The white Volkswagen Harris drove from New York City to Alaska in 1966.

His first major solo trip, in 1966, came together in a matter of days. Having just passed his last psychology final and graduating from Queens College, City University of New York, 22-year-old Harris—the first in his family to earn a degree—sought a trip to help him blow off steam and celebrate. After consulting a map and telling only a few friends where he was going, he packed his beat-up Volkswagen and began driving north. Way north. His sights were set on Circle, Alas., 80 hours and 4,500 some-odd miles from Queens. His objective was to be, for even a moment, the northernmost vehicle in the Western Hemisphere—for there to be nothing between him and the North Pole.

“People thought it was a little wacky that I was going,” says Harris, who sent postcards to friends from points along the way. He achieved his goal, but something else happened, too: He saw mountains bigger than any he’d seen in New York State. He longed to see those glaciers and rivers up close, rather than from a car on the road. He vowed to dedicate weeks and months each year exploring these untouched places. “That,” he says, “was the start of my quest for adventure, and exploration, and my curiosity about nature.”

Between the 1960s and early ’80s, Harris mostly tooled around the Catskills and Adirondacks: rafting in Hudson Gorge, hiking the High Peaks, backpacking along Cold River, paddling North Creek. He would spread out maps across his Queens apartment; his daughter, April Harris, remembers stepping over them when playing as a child.

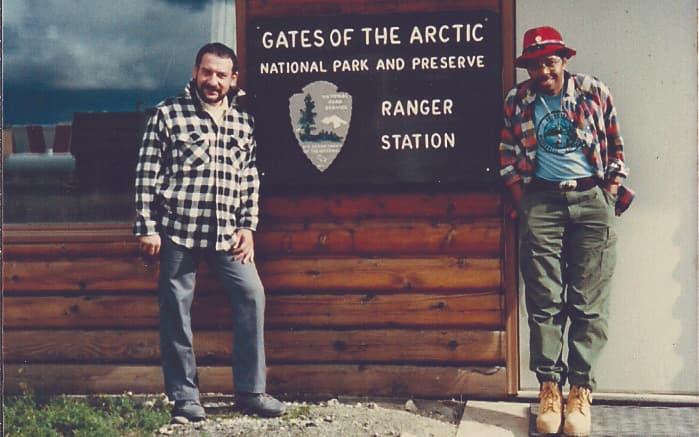

Having picked up Spanish and French as an international marketer for Pepsi, Harris longed to see what he could see abroad. With the marketing company he had founded in 1975 alongside his younger brother, Lloyd, doing well, he began to set aside bigger chunks of time for adventure. Using frequent flyer miles accumulated from work trips, he’d leave the business in his brother’s hands and his two children, whom he was raising alone after his ex-wife’s passing, with his parents, and set off. In 1986, he returned to Alaska, this time to Gates of the Arctic National Park, which he calls the most beautiful place he has ever visited. He took his first trek, a long journey by foot, in New Zealand’s Tongariro National Park, in 1987. From there, Harris began checking more remote destinations off his bucket list: Patagonia, Tasmania’s Western Arthur Range, the Australian Alps.

On many of these trips, Harris connects with groups who rarely experience visitors from the outside world: descendants of the Inca in the Andes Mountains, Aboriginal people in the Australian Outback and Tasmania, and Inuit and Samí people near the Arctic Circle. Those are stories for another day, but you can read more of them in his autobiography, Way Out There: Adventures of a Wilderness Trekker (Mountaineers Books, 2017). Wherever he goes, he says there’s no shortage of curiosity from locals when the black guy from New York shows up in their town or village.

“When you go on vacation, usually you take pictures of people,” he says. “When I go out, everyone wants to take my picture, if they have a camera. I’ve made some really nice friends doing that.”

Harris pauses on a hike near Long Lake in New York’s Adirondack Mountains.

Harris maintains that, in his five decades hiking around the world, he has “never had any race-related problem—even during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s.”

Harris’s longtime friend John Trost, who has accompanied Harris on 14 treks dating back to the early 1970s, remembers encountering a group of hunters in Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness in 1993 and being unsure how they’d react to Harris’s presence. (Everyone went on their way, peacefully.) Trost believes the two were passed up by drivers while hitchhiking along the Alpine Walking Track in Australia due to Harris’s race. “We joked about [him] hiding in the bushes while I flagged down a ride, just so we could get someone to pull over,” Trost says.

If there are other African American trekkers out there, Harris says he hasn’t crossed paths with them. He isn’t sure why. Maybe it’s because African Americans think “black folks don’t go in the woods,” he theorizes, and thus they “won’t be welcomed out there.”

According to Dr. Carolyn Finney, a professor, activist, and the author of Black Faces, White Spaces (UNC Press, 2014), people of color are indeed outside—but often in ways society overlooks, enjoying local parks with family or working the land. As for why there aren’t more adventurers of color, like Harris, it may come back to whom communities of color see represented in contemporary adventure stories.

For instance, Finney, who is African American, surveyed a decade’s worth of Outside magazines between 1991 and 2001, finding that only 103 out of 4,602 photos containing people were of African Americans—and almost all of them were male sports figures in urban settings. “If you’ve never been exposed to something, how would you know?” she asks. “Lacking exposure doesn’t mean lacking affection for or curiosity about the natural world.”

In a talk titled, “I Did It, and So Can You,” Harris tells his story to any school or other type of group who’ll have him. Finney emphasizes it’s not just city kids who can glean truths from exemplars, such as Harris, but all of us.

“I don’t have to look like J.R. Harris to learn something from his story,” Finney says. “At the end of the day, it is the power of that very human story that carries us forward.”

These boots are made for trekking … tens of thousands of miles on nearly every continent around the globe.

I’m doing something that almost no one gets to do: I’m hiking with J.R. Harris. From Manhattan, he has driven myself and AMC’s photographer, Paula Champagne, across the George Washington Bridge to Palisades Interstate Park, in New Jersey. An eclectic mix of jam bands, soul, and hip-hop serenades us through the traffic. The sun is shining bright on one of the first warm days of spring, and the Palisades trailhead is packed as we exit Harris’s Mini Cooper and make our way into the forest, which spans roughly 11 miles of Hudson River shoreline.

Most times, Harris would rather go it alone. It started back when he was a Boy Scout. Having earned his cooking, camping, and pioneering merit badges, he was permitted to take rations of food from the camp mess hall and head out into the woods solo for days at a time. He’d end up spending much of his eight-week session tent camping by himself, returning to the larger troop only on days his parents were up from the city for a visit.

Years later, as an adult, Harris began fielding near-constant questions about where to hike, camp, and paddle, illuminating a potential business opportunity. Along with his friend and neighbor Ken Pepper, Harris cofounded Brokenbo Wilderness Expeditions, leading a few group treks before deciding he really wasn’t that interested in traveling with others. (The only thing that remains of Brokenbo—which stands for “Brothers Ken and Bob”—is the red hat Harris wears on every trip he takes.)

Even at the prestigious Explorers Club, Harris says he mostly keeps to himself. He leverages the organization’s extensive library to research his trips but has never traveled with fellow club members nor been photographed with one of the club’s familiar flags, which have flown on Everest and the moon.

“I don’t want to take somebody else’s flags,” he says. “If I wanted to take a flag, I’ll take my own flag.”

Harris usually hikes alone. One of the few people who joined Harris on a trek was childhood friend and business partner Ken Pepper.

In a rare example of joining in, Harris became an AMC member several years back and attended a few local hikes organized by AMC’s New York–North Jersey chapter—but not because he craved the companionship. “It was really to know where [the hikes] were, so I could go back on my own,” he recalls.

It’s not that he’s introverted or dislikes people, he insists. And from my vantage point, as his hiking companion, he’s perfectly friendly, if quiet. He tells us about towns and neighborhoods just across the river in New York. He nods a greeting to passersby on the trail. He cracks us up with a joke, recalling a trip he took decades ago from memory, his mind as sharp as a brand-new trekking pole. Harris seems perfectly comfortable with our company; it’s just that he’d rather fly solo.

Harris’s daughter, April, now 48, hypothesizes that backcountry solitude is therapeutic for a man who has experienced considerable personal loss: his young ex-wife; his parents; his younger sister; his Brokenbo buddy, Ken Pepper; numerous friends from Queens; and, four years ago, Lloyd—his business partner, best friend, and brother. “Some people read, some people jog, some people drink, some people do drugs,” April says. “[Dad’s] way of decompressing is going out in the woods.”

Even when Harris travels with a close friend, there isn’t much conversation. “When we hiked, we kept to ourselves,” Trost recalls. “We carried our own packs and all our own provisions, and we had no dependency on the other person. If something came up, we’d talk about it at night.”

Harris holds up the red hat he’s worn on countless solo treks across the planet.

Back in New Jersey, we make our way along a flat, tree-covered trail. A few feet to our right, the iconic Palisade cliffs drop toward the mighty Hudson. Harris tells me he’s planning treks in California’s Sierra Nevada and Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains. We also chat about solitude—and silence.

“People say, ‘What do you do by yourself, weeks at a time?’” he tells me. “It’s hard to explain. It’s a way of being in touch with yourself that you can’t do, really, at home, when you go for days without seeing anybody. It’s one thing to be alone. I could go hiking alone in the Grand Canyon, but there’d be a lot of other people there. But when I go hiking in Newfoundland, I don’t see anybody. It takes a little getting used to.”

He pauses then sums it up succinctly: “I really believe, even today, that when I come back from a trip, I’m a different person from the person who went out there.”

EXCLUSIVE PREVIEW:

The Unlikely Thru-Hiker

The following excerpt, about a next-generation trailblazer, comes from Derick Lugo’s new memoir, The Unlikely Thru-Hiker (right), available now.

I catch her gaze as I cross the parking lot of a small-town supermarket. With her head slightly tilted to the right, as if it’s giving her a better understanding of what she is seeing, she moves closer. Her eyes are open wide—not because she’s frightened, although she sure is scaring the hell out of me. It’s like a shot in an old black-and-white thriller, when the camera catches a close-up of the ghoul slowly approaching its victim.

Damn, she’s creeping me out. Does she know me? What’s her deal? She stops a few feet in front of me, and before I can make a run for it, she says, “Hi.”

“Hi,” I tentatively reply. I feel my lips quiver. I hope she doesn’t notice.

“Are you thru-hiking?” she asks.

“Uh, yeah.”

She’s beautiful, with short black hair and skin a shade lighter than mine. She continues to stare, as if studying my face. I get a sense that she wants to tell me something but can’t decide if she can trust me with it. I’m just as lost for words.

“I’m Steps.”

“I’m Mr. ….” I swallow, my mouth feeling dry all of a sudden. What’s my name? I draw a blank, her beauty and her poltergeist stare making me nervous.

“I’m Mr. Fabulous,” I blurt, as if attempting to be the first to answer a question. She nods as if in agreement, but she doesn’t seem to hear me. An inner conversation has her full attention.

“OK…nice…meeting you,” I say, unsure how to converse in this eccentric way.

“Bye,” she says, still wide-eyed. She flashes a big smile that would, in a different setting, be flattering. At this moment, however, it recalls the smile the Joker gives his victims before he shoots them in the face with his long-barreled gun.

I take a couple of steps backward, turn around, and then realize I’m going the wrong way. I turn back around. “Oh, yeah, this way,” I whisper and scurry away.

I go over in my head what just happened. Unsaid words seem to linger in the air, like an indistinguishable scent.

A few days later, when I get a chance to have a real conversation with Steps, I learn she’s not as nutty as our first encounter suggested. In fact, she’s smart and free-spirited. She hikes the trail without rules, in her own way and not on a set schedule. Later, I hear a story that she embraced a black female day hiker and thanked her for being on the trail. And just like that, it all makes sense: She was astonished—and in her way, excited—to see someone of color thru-hiking.

I still can’t get used to the fact that black thru-hikers are so rare out here. I think of my life and of the people closest to me back home. Most, if not all, of my family and friends have never camped or hiked up a mountain. Growing up, the Appalachian Trail was as distant as the Milky Way.

The realization I may be something of an anomaly gives me much to ponder. If more individuals like me, the backcountry-challenged and the urbanites, were aware of this astonishing trail, then perhaps there would be more outdoorsy types of all colors—and fewer unlikely thru-hikers.