Forest Service firefighter Sammy Moore works a prescribed burn in the New Jersey Pine Barrens near Evesham Township, N.J.

Two pitch pines stood alone in a grassy field. To the west, a wetland opened up into a cranberry bog owned by Pine Island Cranberry Company, one of many bogs dotting the landscape in southern New Jersey’s Pine Barrens region. It was late May. Soon wildflowers would sprout, insects fill the air, and northern bobwhite quail chicks the size of bumblebees hop along travel lanes in the tall grass. Aside from the charred lower limbs of the twin pines, the untrained eye could detect little evidence that this landscape burned in late winter, less than three months prior.

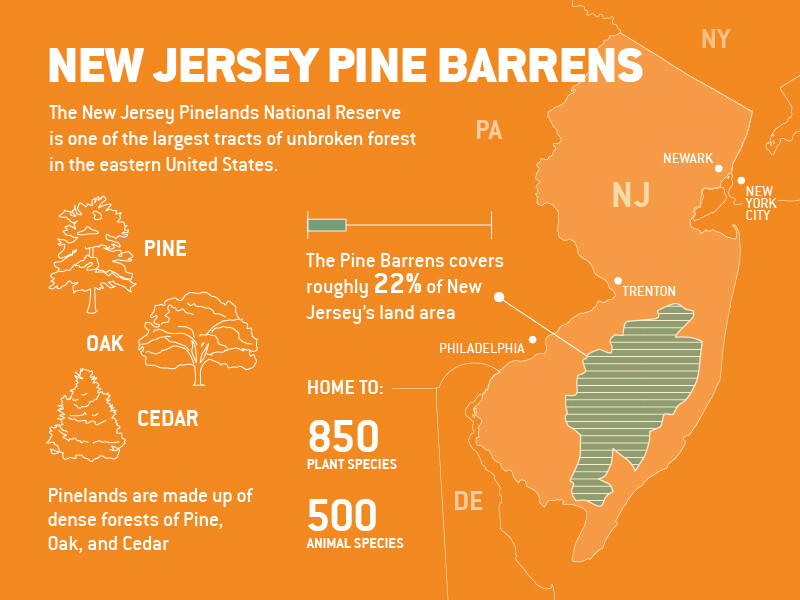

Thirty miles east of Philadelphia, the New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve is one of the largest tracts of unbroken forest in the eastern United States. An urban escape, the 1.1-million-acre New Jersey Pine Barrens, as it’s known colloquially, features a mix of pitch pine, oak, and cedar forestland, and is home to roughly 850 plant and nearly 500 animal species—including dozens of rare and threatened species, such as the Pine Barrens tree frog and the swamp pink orchid. It’s also one of the most flammable landscapes in North America. In fact, scientists who study the physics and ecology of wildfire have long used the Pine Barrens as a laboratory. Those who study fire here are honing techniques for protecting residents in fire-prone ecosystems around the country. They’re also using fire as a tool to restore critical habitats and conserve threatened species in this fragile ecosystem. The stakes couldn’t be higher as record wildfires this year already have burned over five million acres in California, Oregon, and Washington.

Recently, scientists also have learned to use fire to conserve the many Pine Barrens species that depend on fire to create the habitat they need to thrive, such as the northern bobwhite quail. Other Pine Barrens scientists have gathered important data on the spread of embers in both wild and planned fires.

A fire-prone ecosystem

The Pine Barrens comprise a mix of natural habitats that clash with New Jersey’s urban image, though it covers roughly 22 percent of state’s land area. These include dense forests of pine and oak, large tracts of dwarfed or pygmy pitch pines that stand no taller than 13 feet (though many are shorter in stature than the average adult), Atlantic white cedar swamps, and savannah woodlands. The pitch pines are especially important to the ecosystem, as they and other native plants like the broom crowberry—a low-growing shrub with red flowers—are pyrogenic, meaning they rely on periodic fire to thrive.

Here, fire supports many rare and unusual plant species, including wild orchids and the carnivorous pitcher plants, sundews, and bladderworts. New Jersey cranberry farmers have for many decades used fire to maintain the health of the watershed and woodlands surrounding their bogs.

Sandy, acidic, nutrient-poor soils dominate the ecosystem, due in large part to the underlying geology of the region. These sandy soils are prone to drought and help to create ideal conditions for wildfires, says Ryan Rebozo, director of conservation science at the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. Scientists estimate that, historically, any given portion of the Pine Barrens has burned naturally every 20 to 25 years.

Humans have long realized the importance—and peril—of fire in the Pine Barrens. Before European settlers, the Lenape Indians periodically set fire to the forest to drive game for hunting. During the 1700s and 1800s, the population of the Pine Barrens waxed and waned as a number of short-lived industries—from logging and charcoal production to glassmaking and the harvesting of bog iron ore—boomed and fizzled.

Many of the oldest towns in the Pine Barrens were built with a lake or some kind of wetland to their west. That was to protect against forest fires which historically traveled from west to east, due to prevailing wind conditions, says Mike Gallagher, a fire ecologist at the U.S. Forest Service’s Silas Little Experimental Forest in New Lisbon, N.J. The threat of fire was constant for those living in the Pine Barrens. An 1893 New York Times article reported, “Every year brings a reign of terror to the people living on and about the pine lands, and each year from $1 million to $2 million worth of property is destroyed by fire.”

New Jersey founded its forest fire service in 1906 with the aim of protecting lives, property, and natural resources. The early service focused on patrolling the woods, looking for fires and putting them out as quickly as possible. But they soon began to learn that total fire suppression had negative consequences on forest ecology and could actually increase the risk of large, catastrophic wildfires. By the 1930s, a new fire science was emerging in the Pine Barrens that would later inform forestry practices across the nation.

Left: In 1937, foresters burned a 100-foot safety strip along the north boundary of the Lebanon Experimental Forest—later named for Dr. Silas Little. Right: Dr. Silas Little examines the recovery of pitch pines burned in the catastrophic 1954 “Chatsworth Fire,” which burned nearly 20,000 acres near the town of Chatsworth, N.J.

Early fire science

Gallagher scales the 56-foot-tall weather station tower at Silas Little Experimental Forest. The forest canopy reaches nearly as high as the tower. “This area was a lot different 100 years ago. A lot more open,” Gallagher says. By the early decades of the 20th century, the New Jersey Pinelands—like many forests across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic—were transitioning from hundreds of years of industrial-scale logging and agricultural clearing to an era of forest regeneration. What grew back in the Pine Barrens were scrubby, short-statured pines that created the necessary fuel for frequent wildfires. “Imagine a whole forest made up of tinder and kindling,” Gallagher says. These transitional forests burned with much more frequency and intensity than fires from recent memory, according to Gallagher.

New Jersey wasn’t alone. Communities across the eastern half of the United States experienced frequent, catastrophic wildfires throughout the late 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. The Peshtigo wildfire of 1871 in northeastern Wisconsin consumed an area larger than the state of Rhode Island, killing roughly 1,200 people. In Florida, the 1935 Big Scrub Fire in the Ocala National Forest was the fastest-spreading fire in U.S. history, covering 35,000 acres—nearly 55 square miles—in just four hours. Maine experienced its worst forest fire disaster in 1947, when more than 200 forest fires burned across the state that fall, displacing 2,500 people from their homes. The largest and most destructive, the Bar Harbor Fire, burned more than 10,000 acres in Acadia National Forest and destroyed several historic hotels, summer estates, and hundreds of homes in the popular seaside resort town.

Silas Little, a forester from Pennsylvania, moved to the New Jersey Pine Barrens in 1937 to research forest fires and prescribed burns—small, controlled fires set intentionally for the purposes of preventing larger, more destructive fires. (AMC has not, historically, utilized prescribed burns on its managed or reserved forest land in the Maine Woods, but director of Maine conservation and land management Steve Tatko says fire has been discussed as a way to control the spread of fungal diseases.)

Pine Barrens cranberry growers had been setting small fires to protect the property around their bogs from catastrophic fire since the 1800s. But how best to use prescribed burns for large-scale forest management remained a mystery. Little soon realized it was impossible—and undesirable—to prescribe burn the entire forest at once. Instead, he showed that burning a checkerboard pattern on the landscape—reinforced by natural firebreaks such as rivers, swamps, and lakes—allowed foresters to safely and efficiently manage prescribed burns while protecting developed areas.

“The work was highly unique for the time,” says Gallagher, who notes that Little’s pioneering research has since been used to support prescribed burning in Atlantic coastal pine barrens ecosystems throughout the Northeast, in places like Long Island, Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, and even as far south as Florida.

Over time, researchers studying both wildfires and prescribed burns in the New Jersey Pine Barrens gained a better understanding of how prescribed burns help fire-dependent species regenerate. Research in the Pine Barrens also has provided fire scientists with knowledge of how different types of “fuel”—the burnable biomass in a forest, including tree needles, grasses, twigs, shrubs, branches, and downed logs—affect how hot a fire burns, and where, how far, and how fast it spreads.

A New Jersey Forest Fire crewman conducts a prescribed burn at the Silas Little Experimental Forest.

An ideal laboratory

What makes New Jersey’s Pine Barrens a natural fit for conducting fire research? “It’s a pretty flat landscape, without a lot of topography. And the ecosystem has long, unbroken tracts of fairly homogenous forest dominated by pitch pine,” says Inga LaPuma, fire science communication director for the North Atlantic Fire Science Exchange. “It’s a relatively simple and well-understood forest structure and composition with plentiful wildfires and controlled burns,” Gallagher adds. These factors have allowed researchers over decades to answer fundamental fire behavior questions that are being applied everywhere, they say.

Today, researchers who study fire in New Jersey’s Pine Barrens are working to develop remote sensing techniques to gather data from inside the fires. This is especially important for prescribed burning science, according to Gallagher. Ideally, you’d be able to control all conditions for a precise effect, but there’s still a lot to learn. Fire is a fairly blunt tool. No two fires ever look the same, and it’s hard to predict how various forest and environmental conditions will affect outcomes. Fire agencies around the country still worry about their ability to control prescribed burns. It’s one reason the practice remains infrequent among forest managers in the West. The devastating Cerro Grande Fire that resulted in the loss of more than 200 homes in New Mexico, in 2000, for instance started as a prescribed burn that was swept out of control by high winds. As Gallagher puts it, “The holy grail of wildland fire science would be the ability to predict everything about fire before it happens: Exactly where and when will a wildfire occur? Exactly how will it move through the forest? Will the flames and smoke affect people? If so, which people?”

We have the technology now that we didn’t have 100 or even 30 years ago to begin to measure and run simulations that could integrate a lot of data, Gallagher says. This means more precise and effective prescribed burns, he explains—as well as the ability to predict potential wildfire scenarios. “It’s like how meteorologists predict hurricane paths using many model runs under lots of possible conditions. That’s the opportunity we’re approaching with these fire spread models,” Gallagher says.

If calibrated to local conditions, these simulations could allow forest managers to study how both prescribed burns and wildfires would burn on actual landscapes—whether in New Jersey or California. Gallagher also sees this nascent modeling technology as a valuable training tool for firefighters who travel to help stop wildfires beyond their home area, which is increasingly common, especially in the West. Training with simulated fires and responses in unfamiliar forest and environmental conditions has the potential to help firefighters better understand different fire behaviors they may encounter when working away from home, according to Gallagher.

Smoke rises from a large-scale prescribed burn in the New Jersey Pine Barrens in March 2020.

Anatomy of a burn

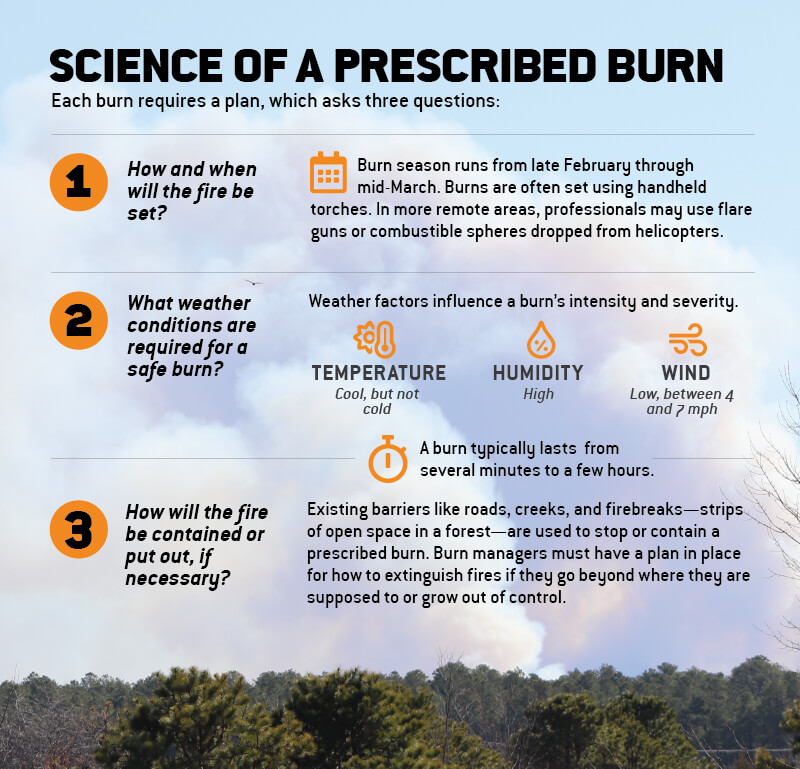

In New Jersey, the controlled burn season generally lasts from late February through mid-March—prior to peak wildfire season, says La Puma. Late March through May present the highest risk for a wildfire, when the air is often warm and windy, humidity is low, and fallen leaves, branches, and twigs are abundant, according to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. This is the time of year that forest managers feel it is safest to set small fires, because weather conditions tend to be conducive to controlling the spread of fire and smoke, says John Parke, New Jersey Audubon scientist and project director. (Even during the season, a very specific set of weather conditions must be met in order to perform a burn—taking into account things like temperature, humidity, and wind condition and strength.) The number one priority in any controlled burn is safety, according to the National Park Service.

Forest managers decide which areas to burn well in advance of the burn season. Each burn requires a prescription or plan detailing exactly how and where fire will be set, what weather conditions are needed and how a fire will be contained or put out if necessary. Weather conditions can influence a burn’s intensity and severity. Existing barriers such as roads, creeks and firebreaks (strips of open space in a forest) often are used to stop or contain a controlled burn. Each controlled burn takes place in a single day, typically lasting from several minutes to few hours.

In the New Jersey Pine Barrens, controlled burns often are set by Forest Fire Service or private land managers using handheld torches, though other methods for setting fires in more remote areas of the country may include the use of flare guns or combustible spheres dropped from helicopters.

Fires usually go out on their own when they reach a firebreak, but prescribed burn managers must have a plan in place for how to extinguish fires if they go beyond where they are supposed to or grow out of control.

Northern bobwhite quail—which depend on fire to thin the forest—have been successfully repopulated in New Jersey’s Pine Barrens.

Conservation success

Back at the recently burned grassy field on the Pine Island Cranberry Company property, Parke awaited the summer crop of wildflowers that will transform this singed plot into a smorgasbord of color and sound in a matter of weeks. Parke has spent decades as a naturalist in New Jersey, though he’s always surprised and delighted by the uncommon native plants that make an appearance after a Pine Barrens burn. “There are rare orchids, lilies, and plant species you see only in books,” he says.

This particular patch is the site of a recent conservation victory to bring back the so-called “firebird” or northern bobwhite quail to New Jersey’s Pine Barrens. Bobwhite quail depend on fire to thin the forest. “A diversity of habitats provides opportunity for a diversity of species,” Parke explains as he parts the tall grasses to expose a pitcher plant, a common bug-eating plant species in the Pine Barrens.

As early as the 1920s, conservationists recognized the importance of prescribed burns for maintaining bobwhite habitat. Prescribed burning can help to remove built-up plant growth that can impede the movement of tiny bobwhite quail chicks. Researchers call these tracts “fire lanes.” It also helps to diversify the habitat of the pine forest, creating a patchwork of pine savannahs amidst the trees. These open grasslands help to increase the growth of diverse plants and insects—an important food source for bobwhite chicks that must quickly grow in order to evade predators.

Yet bobwhite populations have declined precipitously in the last 50 years, with habitat loss from Florida to southern Massachusetts likely playing a major role. In New Jersey, naturalists observed the last known wild bobwhite in the state in 2009.

In 2015, New Jersey Audubon launched a project, along with Tall Timbers Research Station in Tallahassee, Fla., to reintroduce the northern bobwhite quail to New Jersey. The team chose as the study site the Pine Island Cranberry Company’s land. The habitat there was deemed “exceptional,” due to forest stewardship practices the Haines family (the owners of Pine Island Cranberry Company and fifth-generation New Jersey cranberry growers) had maintained on the land for generations, which include prescribed burns on a rotating basis every two years, according to Parke.

In the past five years, more than 300 bobwhite quail, mostly from Georgia, have been released on the New Jersey Pine Barrens site. Parke observed bobwhite quail nests on the property in 2017—the first documented breeding of the species in New Jersey since the 1980s. The small reintroduction project proved that bobwhite quail translocated from Georgia could survive and thrive in New Jersey. The New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife now is considering a larger introduction project to help the species recover to sustainable levels across the state.

Using fire for conservation and management, Parke says, is all about bringing back the natural balance to the Pine Barrens—and elsewhere. “A lot of systems that we thought could take care of themselves are not capable of keeping up with changes on the human scale,” says Parke. Years of fire suppression in fire-prone ecosystems have taken their toll and stymied the natural succession of the forest.

“People are starting to realize now that we really need fire,” he adds. “Hopefully it isn’t too late.”