Known as a “ghost moose,” this adult moose illustrates typical hair loss associated with high loads of winter moose ticks. Climate change, in the form of longer autumns with later snow, lengthens the winter tick season and imperils Northeast moose.

Each fall, legions of winter tick larvae lie in wait on leaves and branches. At that stage, the bloodsucking arachnids are the size of a pencil tip. Once grown, they’re ¼ inch long and a combination of brown and creamy beige; the pattern varies by sex. Those familiar with dog ticks will see the resemblance. Fully fed, they engorge to resemble plump, wrinkly kernels of corn. But first, they’re tiny, born from some 3,000 eggs laid by a single female in late summer or early fall. Together, the larvae crawl up shrubs and other vegetation in search of a host.

Called “questing,” the process is simple: “They just stay on the shrub every day until they get on something,” says Lee Kantar, moose biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. In New England “something” is usually a deer or a moose; while larval winter ticks can latch onto people, nymphs and adults don’t, and the parasites don’t spread disease to us. Larvae can sense large mammals from nearly 22 yards away, and when they land on a host, the young ticks bring along thousands of siblings via interlocking legs. Most tick species move from host to host for their life phases, but winter ticks settle in on just one for the next few months, becoming nymphs, then adults. The parasite “takes…three blood meals off of that one organism, and that’s why it’s so insidious,” Kantar says. And while deer might seem more vulnerable because they’re smaller, it’s the biggest member of the deer family, the moose, whose population the winter tick is slowly decimating, leaving dead calves and emaciated cows and bulls in its vampiric wake.

It’s no secret winter ticks are ravaging northern New England’s moose population. A study published in the Canadian Journal of Zoology in 2018 found that from 2014 to 2016, 70 percent of moose calves in west-central Maine and northern New Hampshire died of emaciation by winter tick infestation. On average, each animal hosted 47,371 ticks. The study also found reproductive challenges. Adults that survive infestation end up much the worse for wear. But why have winter ticks, whose presence in North America predates the moose’s, begun overwhelming the iconic mammal just over the past decade or so?

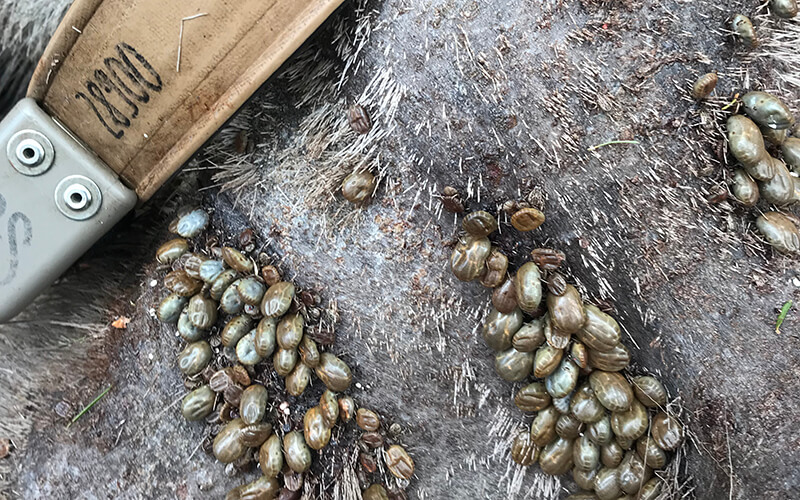

Hair loss and engorged adult female winter ticks on dead moose.

From Spruce Budworm to Climate Change

Kantar answers the question with three points: there are a lot of moose “on the ground;” ticks are out there waiting; and the region’s shorter winters are “egging them along.” Peter Pekins, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of New Hampshire—and a co-author with Kantar on the 2018 study—traces the situation back to the 1970s, when a spruce budworm infestation forced northern New England commercial forest owners to clear large areas of trees. As the forests regenerated, “what it created was the nirvana of moose habitat,” he says. Without predators or hunting, the moose population “just exploded,” he says.

Ever since, “We’ve had moderate to high moose populations that are not what you would typically see in a system,” Kantar says. This was tenable—until climate change reared its head. According to the recent “Confronting Our Changing Winters” report, climate change has affected eastern North American winters the most of any season. That means less snowpack, fewer cold days, and abbreviated winters.

“Every piece that you start to tease apart with climate right now really leads you down the path of just seeing how interconnected and complex the ecosystems currently are,” says Sarah Nelson, AMC’s conservation research director and co-author of the report. “And when they’re changing…potentially all at different rates, that really layers the complexity.”

The report specifically notes that changing winters have fueled the region’s winter tick surge, and that winters are about three weeks shorter than they used to be. This gives ticks more time to quest for a host: “They’re susceptible to getting blown off the shrub or getting frozen off a shrub by snow or freezing rain,” Kantar explains; warmer, longer falls keep them safer. Come winter, “the tick doesn’t care about temperature…it lives right on the moose,” Pekins says. “It really doesn’t matter how warm or cold the winter is, it’s how early it starts or not.”

Lee Kantar—moose biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife—counts winter tick larvae, or nymphs, on a live moose calf in Maine.

Moose in Misery

The combination of shorter winters and lots of moose is ideal for winter ticks—and devastating for moose. Winter tick infestation is “an ugly, miserable death for a calf,” Kantar says. For adults, it’s a miserable existence. Unlike deer, moose don’t notice ticks on their bodies until the nymphs begin to feed. And while deer can effectively remove ticks before they begin to feed, a moose’s cursory five-minute grooming doesn’t do the job. Once ticks are feeding on it, though, this brief routine can become a two-hour ordeal that consumes a higher percentage of its waking hours. This takes a lot of energy—and time away from finding food and eating. Moreover, an infested moose, irritated by the parasites, “basically shivers, trying to…get the ticks off of it,”

They rub against brush, breaking their hairs in half, exposing hair’s lighter-colored shafts, giving the animal a whitish appearance (a moose in such a state is a “ghost moose”). Sometimes, patches of hair rub off completely, exposing skin. “There’s moose that we recover, because we necropsy these moose when they die, and they have really scabby, bloody patches, where they’ve rubbed and rubbed and rubbed themselves trying to get rid of these ticks,” Kantar said.

Moreover, cows are conceiving fewer twins—in a healthy moose population, 20 to 30 percent of births are of twins, but that has dwindled to almost none. Females aren’t as fertile, either, because they don’t weigh enough to ovulate. In the 1980s and 1990s, when the University of New Hampshire tracked yearlings (which are about a year and a half old come winter) “about 30 percent of those cows ovulated and had a calf,” Pekins says. “Today that percentage is zero. Ze-ro.”

Those moose most susceptible to winter ticks, though, are young calves. Born in May, they’re 8 to 10 months old when winter sets in. Over the course of 12 weeks, they lose 20 percent to 30 percent of their weight as ticks feed off them, Kantar says. “They’re just metabolizing their muscle tissue so rapidly, to try and replace the blood. This causes rapid weight loss, acute anemia, and then you die,” Pekins says.

A collared male moose in Maine, having recently survived its first year of life, including its first winter.

Breaking the Cycle

As he continues to study the problem, Kantar seeks to mitigate moose loss. He’s not alone: Mainers have peppered him with possible solutions. These boil down to releasing guinea fowl, which eat insects and ticks in tick-dense areas; spraying those areas with tick-killing chemicals; or treating a percentage of the moose population with anti-tick medication. Each poses “real-world challenges” rendering them unrealistic, he says. Guinea fowl aren’t native to Maine, so the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife “is not going to introduce an exotic, non-native bird that is not adapting to snow in northern Maine across 16,000 miles of privately owned commercial lands,” Kantar says. Spraying the land with chemicals “would probably kill everything else,” he said. As for treating moose for tick prevention, “you could never have enough money to capture moose, treat them with something on their backs or something, like you treat your dogs, and then recapture them,” he says—adding that it’s unclear how many moose would need to be treated to affect tick numbers.

Asking people to reduce their carbon footprint isn’t novel, and research specifically calls out the link between climate change and northern New England’s particularly large winter tick numbers. Yet Nelson and Amanda Shearin Cross recommend just that. Shearin Cross, wildlife resource supervisor for the state of Maine, also suggests creating “the landscape in which species can shift and move as they need to, to adapt to changing [climate] conditions.” For moose, that means supporting and creating “sustainable working forests and other land use practices” that offer large tracts of connected habitat. She encourages people to work with towns and other landowners to do so. AMC’s 70,000-plus acres in Maine’s 100-mile Wilderness are certainly part of the solution.

What holds direct and immediate promise, Kantar and Pekins agree, is an additional controlled moose hunt. Maine’s existing yearly hunt allowed 3,135 permits this year, about the same as last year, and nearly 1,000 more than in 2016. The hunt, conducted, in September, October, and November, doesn’t decrease the state’s moose population, Kantar says. Having an additional hunt might create a smaller, potentially healthier, more fertile moose population. “There’s evidence out there that lower moose numbers could be beneficial because if you have [fewer] moose wandering around in that area, then the winter tick isn’t just getting on a million moose and proliferating every year,” Kantar says. “We can’t count on…early fall snowstorms to kill off these winter ticks. So, if we can thin out the moose, there’s hope that that would break that cycle, and we need to try to figure out if that can function.”

To that end, Maine has begun a study to assess the effects of another moose hunt. In early 2020 and early 2021, that means putting GPS collars on an additional 70 calves. If an experimental hunt happens, it will take place in the fall. While Pekins approves of the study, he knows public support is crucial. “It’s a tough sell. It’s counterintuitive, I get that,” he says.

If nothing else, Pekins wants to get the message out; he’s pushing for moose to be an icon of climate change in New England. “It’s not a polar bear, but it’s damn close,” he says.

“Climate change and global warming affects insects first—in this case it’s a parasite—and that then starts to affect larger animals,” Pekins continues. “This is not about moose getting hot. This is not about habitat. It’s about a little parasite that gets the advantage of just a couple weeks of extended autumn and that’s all it needs. And that’s a scary statement.”