AMC Professional Trail Crew build stone steps on the Crawford Path, in the White Mountain National Forest, New Hampshire. Photo by Corey David Photography.

I’m standing on a 2,000-yard stretch of churned-up earth, right off the road. Sunlight filters down through the trees with just-starting-to-change color leaves, and busily working people in hard hats surround me, as well as one or two brightly colored excavators. As I step forward, my shoes squelch into a good foot or so of sticky mud.

“I’m glad you brought your boots,” trail crew leader Ellie Pelletier laughs.

Ellie is a Trail Crew Manager for AMC, and she’s showing me some of the work her crew is doing on a trail in Maine this fall. They’re not just fixing the trail – they’re completely moving it, redirecting the trail from one side of the road to the other. The previous trail will be decommissioned. It’s a lot of work – and as I learn from Ellie as we walk, trail work has changed drastically over time.

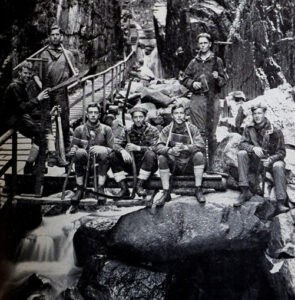

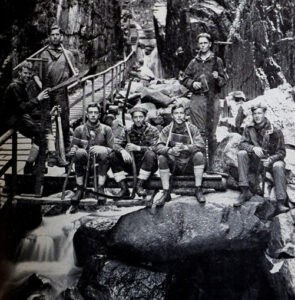

A 1924 AMC Professional Trail Crew.

A History of Trail Trials

AMC has a long history of building and maintaining trails in the Northeast stretching all the way back to the 1800s.

Trails back then were built differently than today. They were constructed as ‘direct routes,’ often ignoring steep elevation gains, thin soils, or areas where water would pool, to get to the destination — usually a mountain top or scenic spot — as quickly as possible. Over time, this led to unsafe and unsustainable trail qualities, like erosion, wide muddy spots or deep standing water.

AMC staff, and visitors, took notice. In the 1970s, AMC began restorative work on some of its trails. Trail crews began to focus on the structures of trails, stabilizing soils and drainage, and using timber and stone for the first time. AMC’s work was innovative for its time. It was the first time trail work was done with an underlying understanding of the issues causing trail damage — high visitor use and initial trail construction which didn’t take erosion or water damage into account.

It was a good first attempt, AMC Director of Trails Alex DeLucia says. Over time, however, the results have proven mixed. The new stone steps, for example, were uneven and awkward, so visitors often went off-trail to avoid them. Trails weren’t redirected, so mud and standing water were still an issue. Trail work in the 70s, 80s, and even into the 90s continued to evolve. AMC’s consistent presence in the White Mountain region has allowed them to study the successes and failures of various trail work techniques over time.

Support the work of AMC’s Trail Crews as they repair the Franconia Ridge Loop for future generations!

Today’s Challenges

There are two main challenges facing trails today: climate change and high visitor usage.

Climate change has caused more unpredictable and extreme weather events. Increased precipitation in already wet areas, for example, erodes trails and creates lots of muddy and wet spots. Higher water levels can completely wash out a trail, removing logs and stones that provide stability and erasing clear signs of where the trail leads. This can cause impassable or hard-to-recognize pathways and greatly accelerates the rate of trail degradation.

When visitors use the trail, they may try to walk around trouble spots like pools of water or deep mud, widening the trail and trampling plants.

Increased usage also wears down the trail, to the point that the trail may be a foot or more below the soil next to it.

Combined, extreme weather events and high visitor use can contribute to fast trail degradation. If repairs aren’t made with these challenges in mind, trail crews may be back out on the same section of trail the next year.

Trails need to be realigned to withstand increased visitor use and climate change impacts over time.

AMC Professional Trail Crew build stone steps on the Crawford Path, in the White Mountain National Forest, New Hampshire. Photo by Corey David Photography.

Realignment

“Re-aligning” a trail means to redirect and reinforce it in different ways, like rebuilding a washed-out section of trail or even moving a stretch of trail to a different location. As opposed to smaller, “stopgap” measures, like adding more soil to a trail, or fixing a rotting wooden staircase, a realignment project moves the trail in a way that works with, rather than against, the natural landscape.

Realignment can include widening trails to make them more accessible, following a gentler elevation grade to prevent dramatic erosion, integrating climbing turns that follow natural topography, or using masonry to cut, split, and shape stones into uniformly shaped steps.

Realignment projects can be difficult to start. The process is costly and requires many specialists to weigh in.

However, realignment ultimately leads to sustainably built trails that can withstand higher visitor use, more rain, and other weather conditions. Sustainably built trails require less maintenance over time and are built with higher visitor use in mind. They’re created to stand the test of time and provide a visitor experience for generations to come.

Surface smoothing on the new Cardigan All Persons Trail, New Hampshire. Photo by Corey David Photography.

The Future of Trails

“Trail work is a tremendous public service in natural resource protection,” says AMC Trail Director Alex DeLucia. Right now, that work is being recognized more by land managers and the public. Alongside new trail building and repair measures, there’s a new focus by AMC and the rest of the trail community on universal accessibility standards. Trail work is changing to include not just new building techniques, but new considerations of who wants to experience the outdoors.

“This is an opportunity for positive change,” DeLucia says. As public awareness of trail conditions grows, there are more opportunities to rebuild, realign, and create outdoor experiences for everyone.

AMC just completed a one-mile All Persons Trail (APT) loop on New Hampshire’s Cardigan Mountain which is fully accessible to wheelchairs, strollers, and those with varying abilities. Other APT trails are in the works across AMC’s region.

Also in New Hampshire, AMC is completely rehabilitating the iconic Franconia Ridge Loop to better withstand increased visitor use and the impacts of climate change, especially increased precipitation events. Other trail builders are following suite, integrating trail-building measures which anticipate more boots passing over the trail and more water passing through.

These trail rehabilitation measures are working. Following the stormy, wet winter of 2024, many trails across AMC’s regions experienced dramatic soil loss from higher-than-usual water volumes rushing down the trails. The realigned trails, however, were different.

“The segments of trail that were worked on looked as if nothing happened, looked as good as the day they were built,” DeLucia says.

Trail work is ever-changing and evolving. Measures have changed drastically since the first direct route trails were built over 100 years ago. They could continue to change and adapt to visitor and climate change impacts.

Compared to historical trail work, DeLucia sees a bright future. Questions about who uses the trail, what the trail currently looks like, and what contributes to degradation are considered for new construction. AMC is leading the way in sustainable, built-to-last outdoor experiences.

“I’d like to think we’ve got it right, finally,” the trail director says.