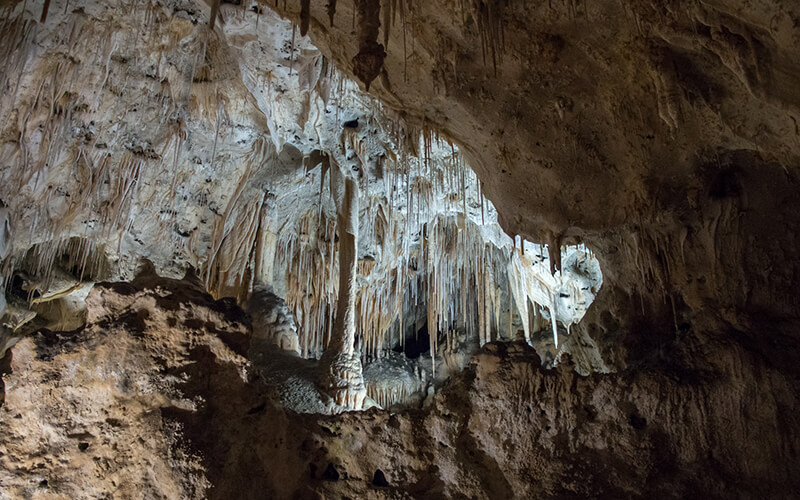

A spelunker explores Lost Run Caverns in Hellerstown, Pa. Cave conservation organizations work to protect natural spaces like these.

Late in the summer of 1996, by the banks of the Colorado River where it crosses through Austin, Texas, a group of researchers demonstrated something remarkable. While examining how water moves underground through a karst region—an area built on porous, soluble rocks, such as limestone—they poured a fluorescein dye into a sinkhole. Their plan was to see where the dye ended up.

A few days later, the researchers located the dye about three miles away from where they put it in, a spot known locally as Barton Springs. The dye had traveled there entirely through groundwater.

In karst regions, water flows through miniscule channels and conduits. Areas like this are located all over the world and scattered across much of the United States. As water seeps through the soluble rock, it dissolves it, creating larger and larger passageways. Over the course of thousands of years, these underground spaces might become big enough for a person to crawl into—at which point you have a cave.

Caves lie beneath the ground in spots as well-known as Carlsbad, N.M., and as inconspicuous as your local forest. Not all are formed in karst—many come from glaciers, lava flow, and other natural methods. Some caves are exposed to the outside world through gaping openings, but most have entrances just a few feet wide, says Jeff Karr, chair of the National Speleological Society (NSS) Cave Conservancies Committee, which calls itself the largest caving group in the world and boasts 10,000 members.

Karr and cave conservationists like him protect caves with the same driving purpose that their above-ground counterparts apply to protecting rainforests or wetlands. Some of these conservancies—the proper term for a cave conservation group—gate cave entrances to allow bats to fly in and out while preventing unwanted visitors from passing through; others organize cleanups that remove trash from cave floors or graffiti from the walls. But many of these groups focus intently on purchasing the land above caves in order to secure protection for the underground spaces.

Purchasing this land is especially effective because it allows the conservancies to control access to the caves. But it also creates a buffer zone between the above- and below-ground worlds. Because water can easily travel through the same soluble rocks that form many caves, humans’ surface-level impact can have immense below-ground effects, says Val Hildreth-Werker, co-chief of the NSS’ conservation division.

Water can act as a transportation device for whatever fluids or substances it carries. So, while the dye that the researchers poured into the ground in Texas was innocuous, other substances, such as fertilizers or pesticides, might not be.

Picture, for example, a well containing drinking water sitting on someone’s property. Down the road is the neighbor’s outhouse, and beneath the ground, water can travel several miles in a short timeframe. What enters the ground through the outhouse can easily leave the ground through the well. It could also enter a nearby cave. Thus, any contaminants that seep into groundwater can have troubling effects on the health of the people, animals, and caves nearby.

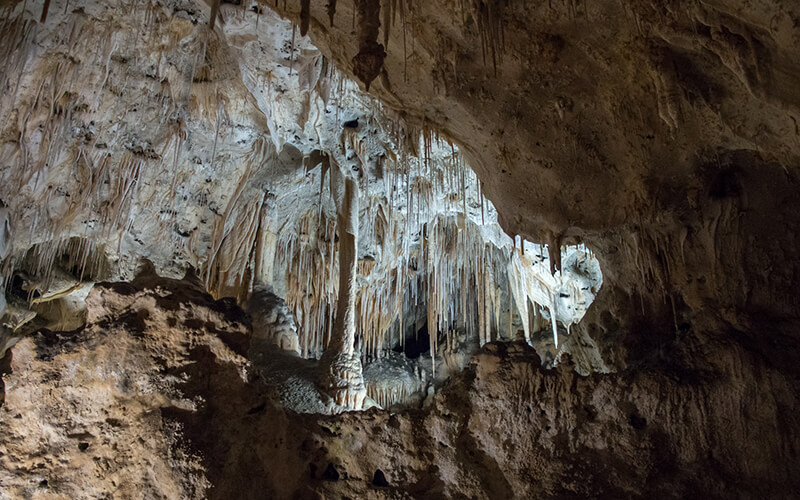

Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico is one of the best-known cave systems in the United States.

Cave Protectors

As with above-ground environmentalism, gathering a coalition that can protect caves means showing people how helping caves correlates with helping themselves. For cave conservancies, this entails showing the public that the formula for protecting caves can also be the one that keeps drinking water safe. More than a billion people worldwide get their water from karst, according to the University of South Florida’s Karst Information Portal. Yet many have never heard the word nor understand what it means, Hildreth-Werker says.

“We can help make the understanding of karst a household concept,” she explains. “It needs public outreach, education, and events that involve people in the wonderful stories of caves, karst, fauna, and habitat.”

For example, when a person dumps trash into a sinkhole, or their outhouse leaks into the groundwater, or a company disposes of harmful chemicals into a landfill, everything beneath the ground—from caves to drinking water—can become contaminated.

“Literally, sewage fluids can be dripping off of stalactites,” Hildreth-Werker says.

For caverns as delicate as the most pristine above-ground environments, those foreign substances can be debilitating.

“Just like there are some landscapes that are so spectacular that they shouldn’t be touched, there are caves that are so spectacular that they shouldn’t be touched,” says R. Laurence Davis, professor emeritus of earth and environmental sciences at the University of New Haven, and science coordinator for the Northeastern Cave Conservancy.

In Jewel Cave in South Dakota or Lechuguilla Cave in New Mexico, the minerals are so delicate that simply breathing on them may destroy them. In Lechuguilla, frosty-white gypsum formations branch out into 20-foot mineral chandeliers. Only researchers or explorers are allowed entry, Davis says. Once a section of the cave is explored, it is rarely visited again.

Even some of the most visited caves in the country host expansive mineral creations thousands of years in the making that could be damaged if not treated with care. In Virginia’s Luray Caverns, among the eastern United States’ largest caves, stalactites and stalagmites combine to form towering calcite columns nearly 50-feet high.

“There is nothing more beautiful in the cave than these scarves, shawls, lambrequins of translucent calcite, some white as snow, falling in graceful folds, fringed with a thousand patterns, and so thin that a candle held behind on of them reveals all the structure within,” the Smithsonian Institute wrote of Luray Caverns in 1880.

Caves are home to bats, mammals that serve many crucial roles that help both animals and humans.

Cave Dwellers

Equally essential to protect are the species that call the caves home, Karr says. “People don’t like bats, but bats are very important.”

They make up about 20 percent of mammal species around the world and are vital members of the global ecosystem, he explains.

“They are tremendous pollinators,” Hildreth-Werker adds. From regulating insect and pest populations, which in turn helps farmers, to serving as indicators of global warming, bats play a crucial role in maintaining a healthy planet.

Bats hibernate in caves and require specific conditions to get their proper extended rest. This is partially why the caves of the Northeastern Cave Conservancy are closed between October 1 and May 1, the bat hibernation period, says Emily Davis, a longtime board member of the NCC and sister of R. Laurence Davis.

If the bats are disturbed, or if the cave environment is altered, it can have devastating effects on the species and, in turn, the ecosystem, Karr says.

For roughly 15 years, that is exactly what has been happening to bats across North America. The populations have been decimated by white-nose syndrome, a disease that breaks up their hibernation cycle.

“And it’s not just that they’ve been dying. It’s that they’ve been really dying,” says Lilianna Wolf, an ecology researcher at Texas A&M University. “There have been population collapses up to 100 percent in some places.”

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is caused by a pale fungal growth on bats’ snouts. The fungus irritates bats and disrupts their much-needed winter hibernation. Awake, starving, dehydrated, and disoriented in a time when they’re meant to be deeply sleeping, the bats cannot survive. Some die in the caves and fall to the cavern floors; others fly out into the harsh winter conditions and die in a last-ditch effort to find food.

WNS was first spotted in North America in 2006 in a cave near Albany, N.Y. Since then, it has spread across the continent, infecting bats in 33 states and seven Canadian provinces.

The fungus may have come from Europe, Wolf says, possibly traveling with a caver who had not properly cleaned their gear.

WNS is harmless to humans, Hildreth-Werker says, but that doesn’t mean cavers should disturb or interact closely with bats. “As with all animals, it’s best not to mess with them,” she says. “After all, we’re visiting in their home.”

As the threat of WNS emerged, cavers had to adjust their routines. To limit the spread between areas, cavers now thoroughly clean their clothes, helmets, lights, elbow pads, knee pads, ropes, and anything else that goes below-ground.

“You used to prove how good a caver you are by how dirty your gear was,” Hildreth-Werker says. Not so much anymore. “Today we say, ‘cave safely, cave softly, cave cleanly.’”

Bats aren’t the only species calling caves home. The caverns house everything from raccoons and snakes that shelter near the entrances, to a vast range of troglobites—fish, spiders, beetles, isopods, and many other animals so well adapted to pitch-black cave life that they couldn’t survive aboveground.

“[You have environments there] that don’t occur in any other place in the world,” Hildreth-Werker says.

The result, she adds, is that “increasingly more disciplines in science are becoming aspects of speleology,” the study of caves. In the field of microbiology, researchers study organisms surviving in the most extreme, isolated cave habitats in the world. “It’s much easier and less expensive than taking robotic devices under the Antarctic ice,” Hildreth-Werker remarks.

But when cavers enter the underground, they might accidentally bring in a microbe that could wipe out a distinctive subterranean species. When polluted groundwater corrupts a cave, it could do the same damage. These are the problems that weigh on the mind of a conservationist like Hildreth-Werker.

“Caves contain this vast resource of cultural and natural heritage,” she says. “Our stewardship becomes increasingly important as science gives us more and more information about what’s really going on.”

Luray Caverns in Luray, Va.

Spread the Word

When the conservancy movement began in 1968, it wasn’t much more than a small group of like-minded cavers hoping to protect what was at the time the longest known cave in Virginia—Butler Cave.

“The values to the [Butler Cave Conservation Society], at the time, were to keep the organization small and protect this one cave,” says Tony Canike, current president of the BCCS.

But since then, the group has expanded its mission. Today, it exists to protect local caves, help researchers with scientific study, and provide community outreach and education about what goes on beneath Virginians’ feet, just as other cave conservancies do in their own home regions.

“You can see a mountain, you can see beautiful forests,” Canike says, so it’s easier for a land or water conservation group to rally around protecting something above ground. People see those things in their day-to-day lives, understand their splendor, and therefore, can be convinced of their value.

“Caves are a little harder, because they’re inaccessible to many people, and to most people, they’re not visible,” Canike says. Making the process even more difficult are the misconceptions people hold about caves. “There’s the typical ones—the bats will get stuck in my hair, they have dangerous animals in them, the air is bad.”

“Ninety-nine percent of the time, those just aren’t true,” he says

Helping spread the word of the hidden underground are show caves, also known as commercial caves, which are accessible to the public. These include commercial locations like Luray Caverns or New York’s Howe Caverns, as well as national parks like Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave. Here, the public can learn about how caves are formed, their biology, and how to keep them safe while walking on guided tours. Oftentimes, the caves have electric lights guiding the way and walkways to keep visitors on stable footing.

Commercialization has no doubt had an impact on the caves over time. “But it has also allowed people to go in and see these caves, experience caves, and begin to learn how important caves are,” Hildreth-Werker says. “So, they serve an incredibly useful purpose.”

“[Show] caves are a great benefit to cave protection,” Emily Davis says. “If the general public goes into a cave, and if the cave is well managed, and the guides are well trained, then they get an idea of what this world is below the ground and why it’s important to protect.”