July 6, 2023

Parker River National Wildlife Refuge in Newbury, Massachusetts. AMC and its partners have worked to add accessible infrastructure throughout the park. Russ Seidel/ Flickr Commons.

It’s in Acton and Ashland. Hanson and Hudson. North Andover, Southborough, Easton, and Westford. In more than 50 communities around Boston, you can hike the Bay Circuit Trail and Greenway (BCT), and at 231 miles, it’s Massachusetts’ longest footpath. If you live in eastern Massachusetts, it could be your closest trailhead.

Trails don’t happen by accident. They take years of planning, fundraising, and construction. The Bay Circuit Trail has taken almost a century to get where it is today. But for BCT Coordinator Callum Cintron, the work is just beginning.

Cintron joins a long list of volunteers and advocates for the BCT. It includes famous figures like Benton Mackaye, “Father of the Appalachian Trail,” and tireless proponents like Al French, who worked on the trail for decades, and at 91 isn’t done yet. Now, it’s Cintron’s turn.

Hub, Spoke, Rim

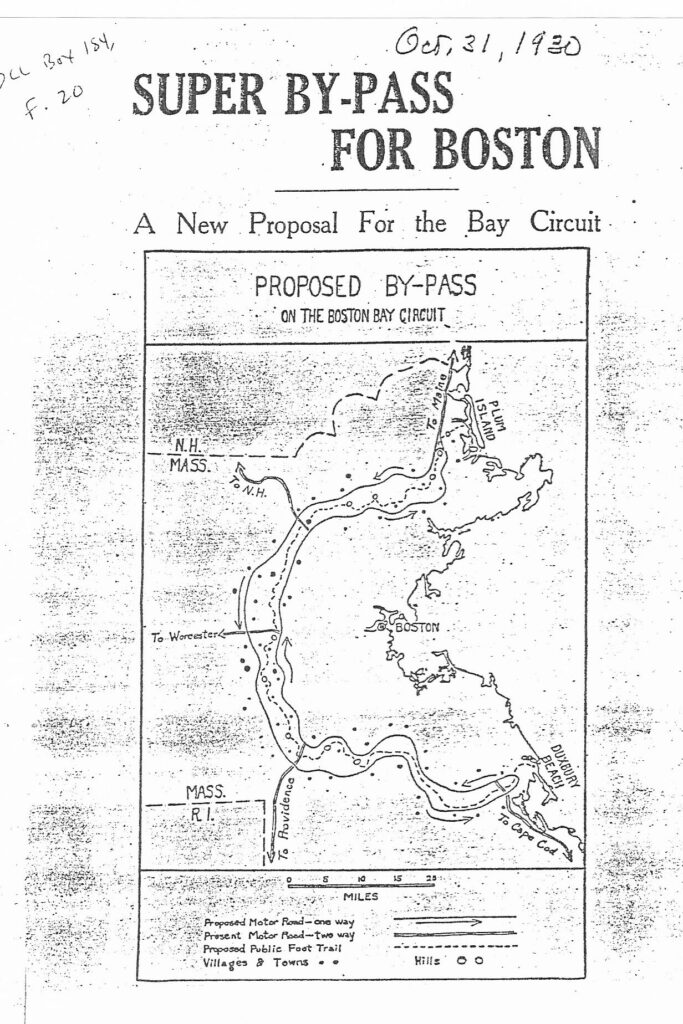

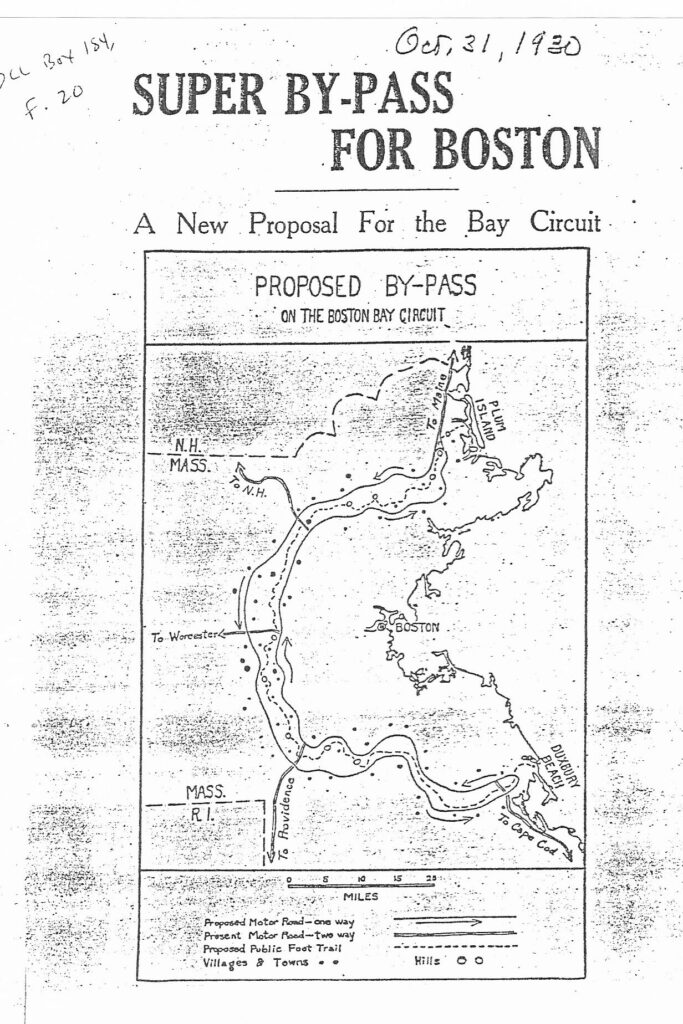

The vision for the Bay Circuit Trail dates back almost 100 years. In 1929, community leaders proposed a system of connected parks modeled on Boston’s Emerald Necklace, one of the first of its kind in a major American city. Charles W. Eliot II, a landscape architect for Emerald Necklace visionary Frederick Law Olmsted, worked on the project and most likely coined the phrase “Bay Circuit.”

Benton MacKaye, Bay Circuit proponent and “Father of the Appalachian Trail.” Courtesy of Dartmouth Library.

Another early advocate for the Bay Circuit greenway was Benton MacKaye. Today MacKaye is known as the “Father of the Appalachian Trail,” after he captured the nation’s attention with the idea of a contiguous path from the South to New England. He also lived in Shirley, Massachusetts and worked with the Bay Circuit founders as a freelancer, sharing his planning knowledge. MacKaye helped explain the vision of the greenway to the public as a “hub, spokes, and rim” system.

“Other people may have used the same term, but [MacKaye] did at least one map that depicted it in that way: the hub in Boston, the spokes were the roads and rail lines out from the city, and the rim was the Bay Circuit itself,” said biographer Larry Anderson in a 2013 oral history of the BCT.

Mackaye saw the potential of the Bay Circuit and thought it could set an example for other cities.

“The Boston Bay Circuit is not the hub of the universe, but it can be made the center of a widening influence on the map of American activity,” wrote MacKaye in a 1931 Boston Globe piece.

The ideas of these early leaders bear many similarities to today’s trail. Eliot identified a northern and southern terminus in Ipswich and Duxbury, respectively, that are close to where they stand today (the northern terminus is now in Newbury). However, his vision for a series of large “open spaces” was never realized due to the 1929 stock market crash and Great Depression. When the Bay Circuit concept was finally revisited in the 1950s, the Boston suburbs were already too developed for the necessary land acquisition.

“My father always said that that is the main purpose of the Bay Circuit: Open space, all the way around…It’s lost in the sense of there being actual park all the way along,” lamented Eliot’s son, Larry Eliot, in a 2013 interview.

An early proposal for the Bay Circuit, dated 1930. Courtesy of Al French.

Close-to-Home Recreation

While Eliot’s dream was never realized, the development that thwarted the “open space” concept has made today’s Bay Circuit Trail more important than ever. Almost five million people live in the greater Boston area. It’s a landscape that ranges from single-family homes on rural acres to sprawling suburbs to dense development. Conserved land is at a premium. There are state parks, historic sites, land trusts, and wildlife refuges. But the BCT is the connective tissue, winding its way through conserved spaces and offering access points for bikers, public transit riders, and drivers alike.

This version of the BCT, a trail network through cities and towns that gives close-to-home recreation to millions, would not be possible without many people. Chief among them is Al French. French didn’t come to Bay Circuit as a trail professional. In 1990, French owned an outdoor equipment outfitting store and attended a meeting organized by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management as a local business owner. His involvement quickly grew until he became the first and only Chairman and Executive Director of the nonprofit Bay Circuit Alliance (BCA) in 1992.

“It was Al French’s shot; he really had the ability to pull people together, and he still does,” said Wes Ward, former Vice President for Land and Community Conservation at the Trustees of Reservations in a 2013 interview. French recounted this time in his life more succinctly.

“I had a small mom-pop store. I had the time, I had the interest, and suddenly I was there.”

While he’s stepped away from the director role, French is still very involved in the trail. In 2012 AMC took on a larger leadership role with respect to the BCT’s maintenance and promotion. This has led to new funding opportunities and a centralized direction. It’s also allowed AMC to hire a Trail Coordinator.

AMC Teen Trail Crew at work on the Bay Circuit Trail in 2019. Paula Champagne.

More Than a Trail

Callum Cintron’s journey to becoming the Bay Circuit Trail Coordinator is a testament to the importance of accessible recreation.

Growing up in northwest New Jersey near the Delaware Water Gap, Cintron was always an outdoorsy kid. While they didn’t consider what they did “hiking,” there were many afternoons spent with family, driving to trailheads, and walking the dog.

That changed in 2015 when Cintron began experiencing health scares. First came the fainting spells, then a stomach bug in 2018 triggered total autonomic nervous system dysfunction.

“I had to stop going to college. I couldn’t work. I couldn’t drive. I was pretty much in bed most days because I was so sick. Because of that I really lost access to nature since, where I live, if you couldn’t drive you pretty much couldn’t go anywhere.”

Cintron was eventually diagnosed with dysautonomia and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), conditions they still live with.

BCT Coordinator Callum Cintron hikes on the Appalachian Trail while attending AMC’s Trail Skills College in New Hampshire. Courtesy of Callum Cintron.

“Once I became disabled, I thought any chance of working in the outdoors, whether it be recreation or resource conservation, was not an option anymore. And that was really hard, with nature being so important to me.”

Despite these obstacles, Cintron found ways to make their dream possible. When college classes went virtual during the COVID-19 pandemic, Cintron re-enrolled. They took classes in natural resource management and met other queer folks who had made the outdoors an important part of their lives.

Offering a similar experience to others is an important driver of their work on the Bay Circuit Trail.

Closing the Gaps

In more ways than one, Cintron’s role as the Bay Circuit Trail Coordinator is about closing gaps. The BCT is not yet a continuous path. Some small gaps between trailheads remain. Cintron works with municipalities and landowners to change that. They also find funding for accessible spaces on the trail.

Each gap in the trail comes with its own unique challenges. In one town, officials were prepared to purchase a necessary plot of land for preservation. But the owner, a corporation that moved its operations out of state, never responded. Another potential area was classified as a Superfund site by the EPA, further complicating efforts.

Creating accessible opportunities has been more successful. In 2022, AMC won a grant from the Essex National Heritage Commission to build an accessible trail hub for the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, the BCT’s northern terminus. Volunteers, including a group from corporate member New England BioLabs, completed the first phase of work, which included new signage, bike racks, and wheelchair-accessible picnic tables. Funding for phase two of the project was awarded by the Essex County Community Foundation in June 2023.

For the next step, volunteers are adding tow rails and handrails to the Refuge’s boardwalk and expanding minimum trail widths to meet Americans with Disability Act (ADA) and Architectual Barriers Act (ABA) standards. They’re also developing signage that gives hikers information about trail grade, surface, and distance.

“In our outreach to disability advocates, we realized that information is so critical. People want to know what they’re getting into,” said former BCT coordinator Mickey Tommins, speaking to Northshore Magazine.

The Bay Circuit Trail’s southern terminus, in Duxbury. Dan Stone/ AMC Photo Contest.

Currently, there are eight accessible paths in the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge.

Accessibility isn’t just about constructing new trail features. It can include demystifying outdoor recreation, so that hitting the trail feels less intimidating for new hikers. Cintron tries to do this with regular social media posts that define outdoor terms. Accessibility also means explicitly welcoming people of all backgrounds and adjusting to their needs. For a recent National Trails Day gathering, Cintron published an event guide with detailed accessibility information.

These actions are just a few examples of the work that continues once construction on a trail is complete. Cintron says they took this kind of work for granted growing up. They assumed once a trail was built, the work was done. Now they know what it takes to ensure that a trail is protected, connected, and available to everyone.

It’s a lesson we should all remember wherever we choose to explore – whether it’s deep in the backcountry, or on a footpath through the suburbs.

Want to give back to your outdoors community? Find Volunteer Opportunities near you.