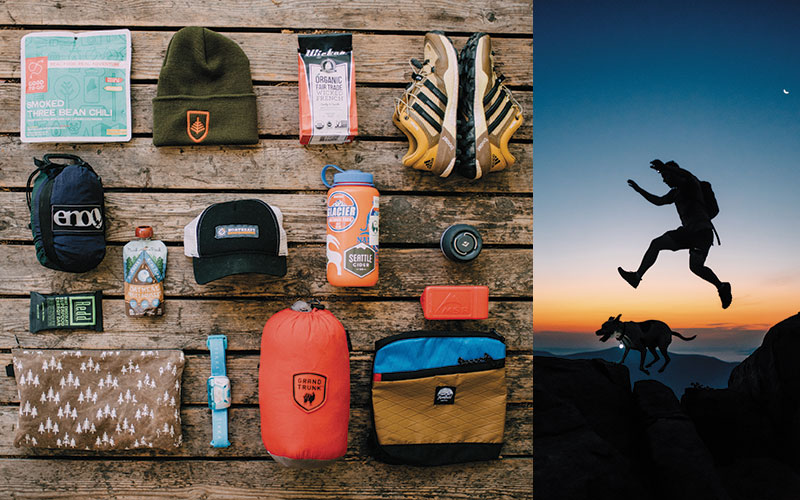

Left: our photographer’s overnight gear spread; right: Fastpacking lets you get an early, high-elevation start.

Are you ready to try fastpacking? For ultralight backpackers and trail runners, the answer might be a speedy: ‘YES!’

Kristina Folcik didn’t know she was about to have her world rocked. A 40-year-old ultrarunner from Tamworth, N.H., she has been zipping up and down trails in the White Mountains for nearly 20 years. In fact, Folcik is such a pro, she was asked to help guide Scott Jurek through western Maine’s Mahoosuc Range in 2015, as Jurek sped toward his Appalachian Trail thru-hike record.

But for all of her years in the mountains, Folcik had never spent a night on the trail before the Jurek gig. “It was amazing,” she says. “We threw down our sleeping bags and pads and slept under the stars. It was so simple.”

Welcome to fastpacking.

Fastpacking is a little like ultralight backpacking. It entails strapping a small amount of gear, water, and food on your back and traveling at a good clip, by foot, for days at a time, often into the deepest wilderness. Carrying minimal equipment allows a fastpacker to move quickly while still being self-sufficient, even in remote locations.

Fastpacking is also a little like trail running. Ben Luedke, a 45-year-old distance runner who has been fastpacking for six years, jokes: “Fastpacking is what happens when you take a trail runner and tell them they don’t need to make it home for dinner. Seriously, though, fastpacking is simply ultralight backpacking with the intention to run, when possible.”

In short, for an activity that can feel so revolutionary, fastpacking is basically ultralight backpacking for runners—or, put another way, trail running for ultralighters: staying on-trail for overnights, and traveling light and fast. For sure, a fastpacker isn’t always running. The simplest way to think of it is hiking the ups, jogging the flats, and running the downs.

Grayson Cobb, of Norfolk, Va., started running with his dad when he was 9 or 10 and has fastpacked along the Appalachian Trail, Glacier National Park in Montana, John Muir Trail in California, and the Grand Canyon. “Fastpacking doesn’t have to be some brutish, grueling slog,” he says. “Fastpacking is less defined by the absolute weight of your pack or the miles you do in a day so much as by a philosophy of moving quickly through the woods, uninhibited.”

Over the last decade, the sport has exploded in popularity, particularly among the ultrarunner crowd. Like Jurek, an increasing number of runners are angling for Fastest Known Times (FKTs) on specific routes. When those routes are long trails, such as the Appalachian Trail, setting an FKT requires going lightweight and spending nights on the trail. For these elite athletes, every minute counts.

That said, fastpacking isn’t only for superhumans. While it’s not an endeavor anyone should jump into unprepared, it’s a great next-level challenge for trail runners eager to see remote locations and for experienced backpackers looking to lighten their loads. “It can be absolutely freeing, with less suffering than pack mule-ing 40 pounds down the trail,” Cobb says. Ready to get started? Read on.

THE UPS…AND THE DOWNS

Fastpacking can be done at three levels: unsupported, self-supported, and supported. Unsupported fastpackers make no use of outside assistance along the route. They carry all of the supplies they need, from beginning to end, with the exception of water, which they source and filter along the way. This is considered to be the purest form of fastpacking. Self-supported allows you to store supplies en route ahead of time—in shelters, at post offices, or other facilities—and pick them up as you go.

And then there is supported fastpacking: Jurek’s AT method and the type often used by trailrunners looking to set a record. “Supported” means having a crew that meets the runner at various checkpoints, providing supplies or needed assistance. That support was something of a double-edged sword for Jurek, who was fined for having more than 12 friends with him on the summit of Katahdin, the endpoint of his quest. The controversy over Jurek’s record has also fed the question of whether those traveling fast are necessarily less thoughtful or careful of the enviroment.

Jennifer Pharr Davis, who set a previous AT thru-hike record in 2011 and recently published the book The Pursuit of Endurance, says: “I don’t think fastpacking or FKTs have any inherent negative impact on the trail or the trail community. A hike that takes less time and uses minimal or ultralight gear will leave less of an imprint on the footpath than an extended journey, a group endeavor, or one that uses traditional camping gear.”

The fastpackers I spoke with were slow to volunteer any negatives. When pressed, they admitted that speeding past fellow trekkers hinders the formation of friendships, a hallmark of many a thru-hike. And traveling at quicker speeds does mean less time to enjoy the scenery.

“The only drawback is having to survive with fewer comforts,” Folcik says. “The trade-off is being able to see so much more in a shorter period!”

PRE-TRIP TRAINING

Just as a potential fastpacker needs to be conscientious of the environment, she also must know her limits. “Like with anything, you have to have a continual awareness of the environment in which you’ve chosen to recreate,” says Kristi Hobson Edmonston, an outdoor leadership training instructor for AMC. “Mother nature is ever-changing, just as your body is every-changing, and you have to keep all of those elements in mind.” That’s doubly true when traveling faster than usual, with less gear than usual.

For that reason, among others, a direct jump into the world of fastpacking is possible but not advisable. Running long lengths of trail with a pack on your back involves mental and physical strength. Plan to slowly build up your stamina on training runs and trail races. Joining a local trail-running club is a great way to begin increasing your endurance. “If your goal is to go out for three nights and four days, you want to start by testing out all of your gear, by going for extensive day hikes, by working up to it,” Hobson Edmonston says.

“I’d suggest being comfortable with trail running and backpacking first,” Luedke says. “Provided that both of those are in good order, fastpacking should be a breeze.”

Running marathon or ultramarathon distances isn’t necessary for successful fastpacking. What is critical is planning your route according to your skill level: If your longest run is 10 miles, plan on some 5- to 10-mile fastpacking days. And remember that you can take walk breaks.

“Often on trips with days of over 40 miles, I’ll stop midday and take a nice siesta,” Cobb says. “Being in shape and in tune, and having things dialed in so well that you can just bounce around on gnarly trails that would slow other people, is absolutely the most freeing way I have found to travel through the backcountry.”

Not everyone is Cobb. Most important is knowing your own body. Jon Paul Krol, who lives in New Hampshire’s Pinkham Notch, has run nearly as many ultramarathons as his age, 33. Having fastpacked in the White Mountains, the Green Mountains, and the Smokies, he has built his life around peaks. Still, he says: “I’ve had some chronic injuries that have opened my eyes to the importance of yoga, balance, and core strength work. It’s dull compared to running, but I try to do some maintenance a few times a week.”

PLANNING YOUR ROUTE

Your choice of fastpacking route should take several factors into consideration. For one, there’s picking the best time of year for a specific trail system. Temperature and bugs vary according to the season, which in turn will determine your shelter and clothing needs. “If it’s 69 degrees in Boston, what will it be like in the White Mountains?” Hobson Edmonston asks. “You have to translate these kinds of considerations to the actual environment you’ll be in and ask yourself if you’re willing to make those compromises.”

What’s more, “Trails could have plenty of water earlier in the year but be completely dried up later, and the amount of daylight changes from season to season,” says Jeff Pelletier, a five-year fastpacking veteran from Vancouver, British Columbia. “You’ll need to pay careful consideration to the chances of the weather changing unexpectedly”—a rule that any smart hiker knows like the back of her hand.

Luedke likes to come up with a plan but will always adjust it, if the weather dictates. “You want to have your intended route in mind, know if there are any permits required, read recent trip reports from the area, and make sure that loved ones know exactly where you’re headed and when you plan to be back,” he says. “I always have a paper map of the trails in the area I’ll be visiting, and I like to download a digital version to my phone.” Luedke says his current favorite app is Gaia, which lets him follow his progress in real time, even in airplane mode, which doesn’t drain his phone battery as quickly as having data turned on. It’s also smart to carry some form of identification, and the name and phone number of your contact back home.

Other considerations when planning a trip: climate, terrain, access to water, remoteness, wildlife, and daily mileage. When setting a distance goal, make sure to account for variables, such as elevation gain and loss, weather, trail conditions, and the technical skill required. (Do you need to be able to climb? Are you sure-footed along steep drop-offs?) As Luedke notes, many areas require permits to camp. Figuring out all of the logistics takes time and research, only one of the reasons most fastpackers choose to go with a partner. From a safety standpoint, partnering up always makes sense—especially if you find someone more experienced who can lead the way.

CLOTHING, GEAR, AND FOOD

On trail, your backpack will be your best friend or your worst enemy. Choose your pack wisely and be sure to test it out ahead of time on long training runs. Other must-haves include the 10 essentials you’d carry for hiking, including a method of storing and purifying water, a flashlight or headlamp, a basic first-aid kit, a pocket knife, a whistle, duct tape, a cell phone, and a map and compass. Then add a few things you might not carry on a day hike: a lightweight sleeping bag, pad, and tent, plus matches or a fire starter, a lightweight cooking stove, and food measured to the gram.

“When preparing for a lightweight trip, it’s important to eliminate the luxury items,” Pelletier says. “For fastpacking, you need to take this even further, by cutting extra straps, cutting calories, and making sure everything you bring serves a dual purpose.” That includes clothes you can wear during the day and keep on overnight for extra warmth, which also means you can pack a lighter sleeping bag.

Hobson Edmonston stresses the importance of thinking creatively when you’re carrying such a limited amount of gear. “I read this really great article by the Harvard Business Review that talks about how we tend to look at an object and stick to its known use,” she says. Whereas with fastpacking, “You have to be able to think about how many uses one piece of gear can serve. You have to think about your gear as systems, as opposed to ten specific things.”

When it comes to clothes, the goal is to keep moving as fast as possible, which makes technical running gear vital. As with your backpack, be sure to test clothes out ahead of time. Unlike day-hikers or backpackers, some fastpackers will skip the rain gear, choosing to run themselves dry. Although Luedke likes to carry as little as possible, he does indulge in an extra wicking T-shirt and an extra pair of socks. “In the mountains, weather can change quickly, so I like to plan for cold temps at night, regardless of season, as well as for the possibility of rain.”

Hobson Edmonston puts it bluntly: “Am I willing to wear that lightweight windbreaker when the deluge comes?”

As for food, fuel is essential to your success. Not enough food is detrimental, while too much food will weigh you down. Pelletier says ultramarathons have helped him hone his personal system. “Cooking or rehydrating food is often seen as a luxury, compared to simply eating dry food,” he says. “But having a warm meal after a long day, and warm coffee in the morning, could provide the mental boost you need.” He also recommends planning some variety in your diet, for longer trips, as “your favorite go-to meal could end up being completely unpalatable by day 3.”

If you won’t eat it, it won’t do you any good. “My advice in a nutshell?” Cobb says. “Take food with no water content, with little packaging, do the math to see how many calories per ounce, and at the end of the day, throw all that out and take food you like to eat.”

A LAST WORD

Do plan and train, but don’t be intimidated. “Get out there and fail,” Krol says. “It’s a personal relationship between you, the trails, and what gear works for you. Everyone figures out their own system over time. Try to keep it light and remember: You carry your fear.”

LEARN MORE: KRISTINA FOLCIK’S 2- TO 3-DAY PACKLIST

- 40-degree mountaineering sleeping bag

- Inflatable sleeping pad

- Hammock

- Wind shirt

- Lightweight puffy jacket

- Light tights

- Long sleeve technical-fabric shirt

- Shorts

- Dehydrated meals

- High-calorie snacks, such as pepperoni, nuts, almond butter packets, and candy

- Light hat and gloves

- Sunglasses

- Stuff sack

- Space blanket

- Ultralight 30-gallon pack

LEARN MORE: 3 FASTPACKING TRIPS IN AMC’S REGION

- Catawba Runaround, Southwest Virginia. This 35-mile loop includes the Virginia triple crown: McAfee Knob, Tinker Cliffs, and Dragon’s Tooth. More info.

- Mahoosuc Trail, Maine and New Hampshire. This 31-mile route boasts the toughest mile on the Appalachian Trail and 10 peaks totaling more than 10,000 feet of gain. More info.

- Pemi Loop, New Hampshire. This 31.5-mile loop climbs and descends, offering awe-inspiring vistas of the Pemigewasset Wilderness. More info.

FURTHER READING

- Rediscover the 1916 dawning of the ultralight movement.

- Read about one writer’s introduction to the Mahoosuc Trail.

- Get a primer on trail running.

- Find trail runs near Boston in the new blog Running Wild.

- Follow Folcik’s adventures at dangergirldh.com.