Hikers today enjoy more clear days in the White Mountains than they would’ve a few decades ago, thanks in part to the Clean Air Act and AMC air quality advocacy.

Fifty years ago, Congress passed arguably the most important environmental and public health legislation to date: the Clean Air Act (CAA). By setting emissions standards for vehicles and industrial factories, the act has removed harmful, airborne pollutants in and around cities, as well as improved the air high above sea level.

Georgia Murray, AMC’s staff scientist, has been monitoring air quality in the White Mountains for two decades. We asked her to explain what she’s observed in that time—and how the Clean Air Act of 1970, and its 1977 and 1990 amendments, helped. Spoiler alert: air quality and visibility New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest have both improved greatly, and AMC has been engaged in the work almost from the beginning.

AMC Outdoors: If you were to go on a hike in the White Mountains a few decades ago, what might you encounter in the way of air pollution and quality?

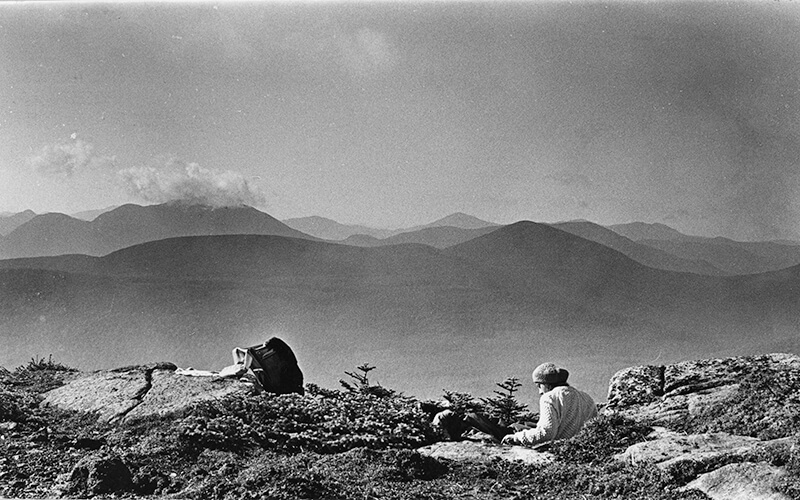

Murray: You would’ve seen more days that the skies were hazy from mountain peaks—you couldn’t see as far. You would more likely have encountered a day where ozone pollution was higher. Often that came together. Ozone is not something you can see, but smog comes in this mixture that includes ozone and fine particulates.

What caused these issues?

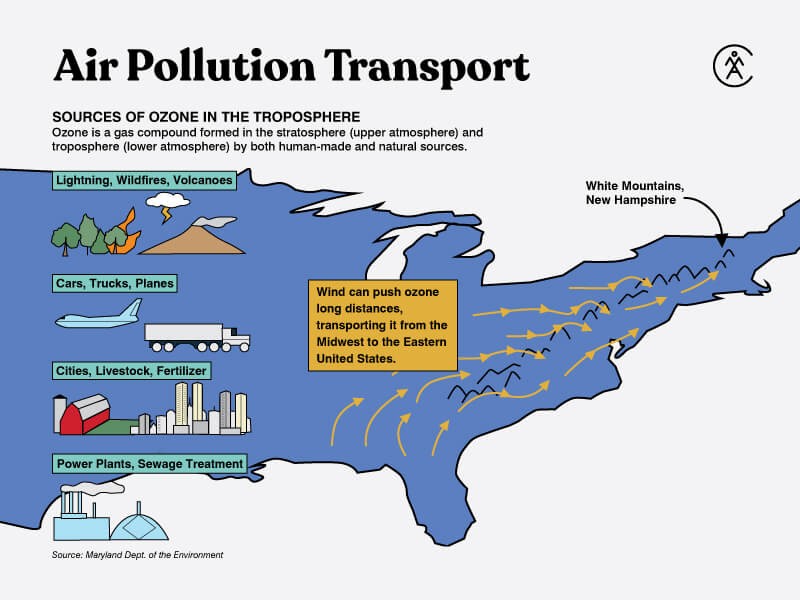

Smokestacks and tailpipes. A few decades ago, you had a lot more coal being burned in the Midwest, and that pollution gets up into the higher atmosphere and can travel to the White Mountains. The cumulative emissions of auto emissions along the eastern seaboard can, on a hot day, get cooked up forming smog and travel to the White Mountains.

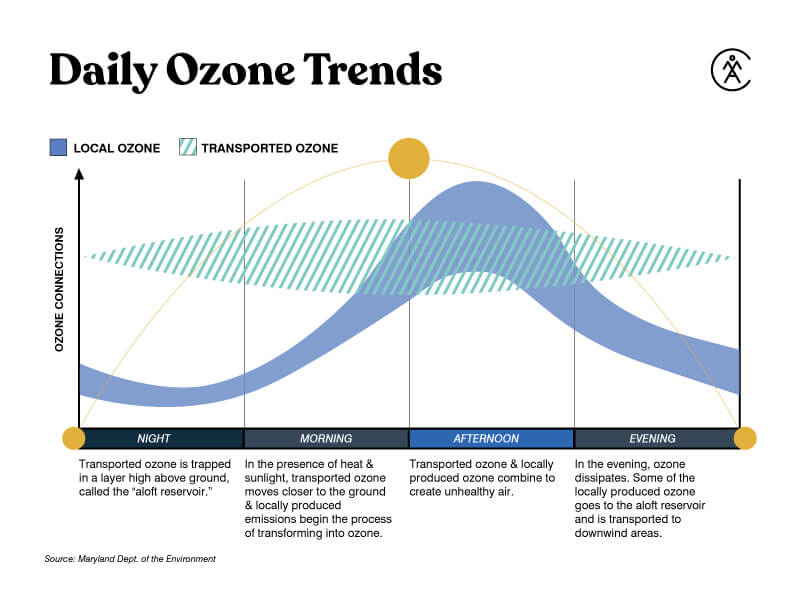

Meteorology is a core part of how these pollutants get to the White Mountains. On hot, humid days, weather is often coming from the hazy Midwest or the Northeastern corridor urban areas. Ozone forms from these source emissions like nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds being cooked in the atmosphere, and especially high-pressure events that last a few days might make the air stagnant. High-pressure systems tend to just sit with little wind, mixing, or moving of air. This allows pollution to build up and get transported at night. Ozone is highly reactive, so when it moves and hits surfaces it dissipates. When it comes above the planetary boundary layer, it doesn’t hit any surfaces until it hits Mount Washington and other higher peaks. Today, we have a hot, humid day but the air pollution is lower and a polluted air day in the White Mountains less likely.

Decades ago, air pollution transported from states to the west created haze in the White Mountains.

How might this have affected a hiker’s experience in the mountains?

During a high-ozone day you might recognize that when you are breathing, you feel a burning sensation or even feel out of breath. In 2002, we had a really bad ozone event where a few people had to be treated with oxygen on top of Mount Washington. In EPA’s health messaging, [breathing in ozone] is like getting a sunburn on your lungs. Today, it’s more the chronic [ozone] exposures that is of concern and for people with respiratory disease.

Families that planned their whole summer around a weekend or a week in the White Mountains could get there and not be able to see the magnificent views of peaks in distance because of the pollution. Or, if they have asthma and it was a high-ozone day, they’re going to struggle in that kind of air. Their experience is going to suffer on a day with high air pollution compared to a day where there is not.

Our hiker health study—which in 1998 correlated the impacts of ground-level ozone pollution on lung function and hiker health)—found that even healthy hiker can be affected by air pollution in the mountains. When AMC was tracking air pollution levels on Mount Washington, we’d ask hikers at Pinkham Notch Visitor Center to blow into a respirometer, before and after they hiked on Mount Washington. What we found was people’s lung function declined on days when ozone was elevated. We saw it even more for people who had respiratory disease. This is a core piece of science that supports AMC’s work to reduce air pollution for all who play and work outdoors. People exercising outdoors breathe more heavily and deeply and are getting even more exposure than others.

What was the Clean Air Act, and how did it start to change things in the mountains?

The Clean Air Act is a bipartisan law that is the foundation of important clean air policies that protect our health and our environment from the harms of outdoor air pollution. That’s a big job, and there are different programs under the act that work to address different pieces of this issue. The act has a program that deals with measuring how much pollution is in the air and setting health standards based on the latest science, reducing emissions around power plants and automobiles, and returning Wilderness to pristine conditions. AMC works on all of these issues to protect wilderness, human health, and the environment.

It was understood at the start of the CAA that visibility was being affected by air emissions. But the science of measuring the specific pollutants responsible took some years to play out as did the development of the policy to reduce them, and then the EPA put the Regional Haze Rule into place in 1999, detailing for states which pollutants needed to be reduced, how they can reduce those emissions, and how to track progress towards the goal of “pristine visibility.” Since implementation of the rule and emission controls, we have seen improved visibility in the White Mountains.

The Clean Air Act set up some really important protections that have been implemented over time. Each state has to come up with a plan for managing air pollution. And while it’s important that they address emissions in their state there are some states that also receive a lot of transported pollution, like ozone and particulates that cause haze, from the Midwest and eastern corridor.

Acid rain is another area AMC has been working on through the years. Under the CAA it was recognized that sulfur was a pollutant, but we didn’t get the acid rain amendment until 1990. Implementation started in 1995. The Acid Rain Program reduced sulfur dioxide emissions by 1.5 million tons since 1990—a 91 percent reduction, according to an EPA progress report.

Here in the mountains, we have seen huge progress in reductions in acid rain, ozone, and in improved visibility. The CAA has worked well for the White Mountains and can continue to if strongly interpreted and implemented. Just as we have advanced in our understanding of air pollution and its health and environmental impacts, we also have a clear understanding that greenhouse gases are an air pollutant and are affecting our environment and our health. The same successful tool, the CAA, should be used to tackle climate change.

How has AMC been involved in this work?

We started monitoring acid rain and clouds in the White Mountains in the early 1980s. We partnered with scientists who were doing acid rain research at the U.S. Forest Service Hubbard Brook Experimental Research Station in White Mountain National Forest in Thornton, N.H., to look at regional cloud and fog water chemistry. AMC’s Lakes of the Clouds hut was a good place to catch clouds, where AMC could have seasonal staff operate the collector, and we have maintained the monitoring every summer for more than three decades.

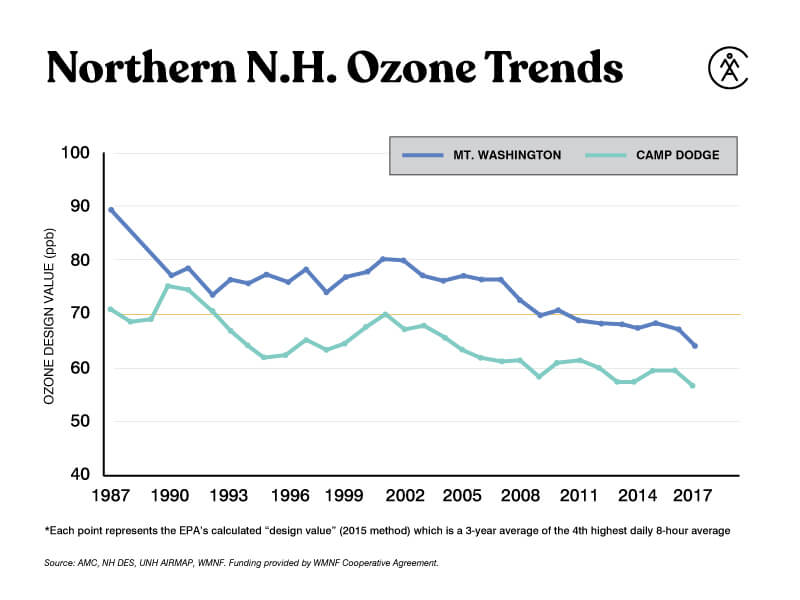

In the mid-1980s we also started tracking ozone with a researcher from the Harvard School of Public Health. Ozone pollution was on the rise in the Eastern U.S., but little information had been collected in the northeastern mountains at that time. Our data demonstrated that high concentrations of ozone were being transported to Mount Washington and at times was as unhealthy as urban air, yet nearby in Pinkham Notch, at the base of the Auto Road, the levels were not as high. In 1990 we began to collaborate with the state of New Hampshire and the White Mountain National Forest in tracking and reporting the air quality and eventually encouraged New Hampshire to add a high-elevation regional forecast when they issue air quality alerts when ozone or fine particles are elevated. If the state does declare an air alert for the mountains, AMC huts staff report this to guests with the morning weather.

Again, partnering with Harvard School of Public Health, AMC instituted fine particle sampling at Camp Dodge and Lakes of the Clouds hut in 1987. Fine particulates can be unhealthy to breathe but can also cause poor visibility. Our monitoring was again capturing data at upper elevations where few were observing, and the study concluded around 2007. The levels we were seeing when I first started in 2000 could reach concentrations of concern for the health standard, but the visibility impacts were most severe. Now, the science around particulates has really evolved, and we know that even low levels are not good for us to breathe. The good news is that the levels are getting lower and lower and views clearer with CAA implementation.

Finally, we’re monitoring stream chemistry at upper elevations and at wilderness boundary sites. AMC is getting some baseline information around acid rain’s impact on wilderness watersheds specifically, funded by a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Forest Service for baseline monitoring.

Since the advent of air pollution regulations in the 1970s, AMC air quality monitors in the White Mountains have observed a downward trend in ozone levels.

What are some markers that would indicate success of the CAA in the White Mountains?

One of the most important indicators is that we’re setting and meeting strong health standards. Right now, we are achieving the current health standard for ozone, but the science indicates it should be even stronger. Anything that causes human health issues, like ozone, should remain on a downward trajectory. We need to hold the line on some of these programs that we know are, unfortunately, being undermined by the Trump administration by being rolled back, but also implementation and some enforcement are being undermined. That’s why monitoring is really important.

Success will also be in understanding the recovery. For example, we’re seeing more organic carbon coming out of the mountain streams and ponds. Understanding the science around some of these upper elevation sites as it relates to changing water quality and chemistry can only be done with continued monitoring. We know things have gotten cleaner, but we don’t know how acid rain recovery is going to play out after decades of impact and as other things continue to change like climate.

What can we do to see the mountain air and waters get even cleaner?

By making sure that science is front and center in our work and in the CAA’s implementation, and that protections aren’t rolled back. We would like to see much more science in the regulatory process than we’ve been seeing of late. In the current administration, we are losing ground on the clean air protection advances we have worked on for decades and rely on for a healthier future.